Ooh, watch the barriers

Once or twice in a club’s history, a manager comes along who not only delivers success but goes beyond it to define a whole era. On the cold last Saturday of January 1970, two of them met at the Victoria Ground, Stoke. For the home side, this was year 10 of Tony Waddington’s 17: for visitors Leeds, Don Revie was nine seasons into his tumultuous thirteen years at Elland Road. Both were nearing the peak of their powers. Within 2 years years Stoke – who had narrowly escaped relegation six months previously – would reach two FA Cup semi-finals, win the League Cup and play in Europe. Reigning champions Leeds would end this campaign as runners-up in League and Cup, and as beaten semi-finalists in the Inter-City Fairs Cup.

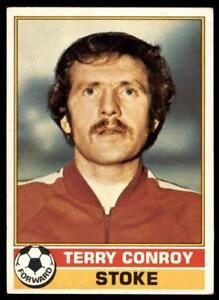

The game ended 1-1. Dobing scored for Stoke, and Giles for Leeds. The home team was Banks, Marsh, Pejic, Stevenson, Smith, Bloor, Conroy (Eastham), Dobing, Greenhoff, Skeels and Burrows. Leeds lined up with Sprake, Reaney, Cooper, Bremner, Charlton, Hunter, Lorimer, Clarke, Jones, Giles, and Madeley. This is the point at which arlarses usually say “I wonder what those teams would be worth today?” But let’s not. Let’s talk graveyards.

Ask any fan of a certain age their biggest memory of going to Stoke, and chances are it will be the graveyard you passed on the half hour walk from the station to the ground. Going, it was on your left: coming back, on your right. Here is a Preston fan, on www.pne-online.net :

“That walk back to the station was very scary – Stoke fans mixing in with the escort walking past the graveyard. One skinhead even managed to get on the train and offered everyone out.”

A Wolves fan on www.molineuxmix.co.uk puts it more prosaically, recalling “in the 70s I remember it always kicking off in the graveyard with the clayheads.”

And finally, here is Spurs fan Malcolm Freeman in Lads: “As the lads passed the low cemetery wall on their left, they were never surprised when about two to three hundred wide-trousered youths stormed across the graveyard lobbing bricks from leather-gloved hands. The next stage in this annual dance was the Old Bill trying to stop the Tottenham fans from retaliating by somehow getting their dogs to bark ferociously. They would be ignored. Tottenham would swarm over the wall into the graveyard and, using discarded Stoke ammo, return fire. After the game the result was always similar. Lots of tired Stoke legs, two Stoke black eyes, four Spurs bitten arses.”

Blackly humorous, but this was far from being good clean fun. A Stoke fan lost an eye after that Preston game, stabbed in the face with an afro comb – “they were seen to jump over the wall into the graveyard”, said police. And the same Wolves veteran goes on to say “I remember seeing clayheads there with razor blades stuck to the front of their shoes.”

The Stokies in the Spurs account would be Northern Soul boys, wearing the single leather glove and wide flares of their kind. In early 1970 the Golden Torch in Tunstall was thriving: like Manchester’s Twisted Wheel, it was a legendary Sixties venue attracting amphetamine-fuelled dancers from across the Midlands to its all-night sessions. The term “Northern Soul” was just two years old, coined in 1968 to describe the mid-1960s era of Motown-sounding black American dance music preferred by the die-hard soul lovers of Northern England. Wigan Casino was still three years away, but Stoke was already a-stomping and a-shuffling.

- Tunstall’s finest

- a-stomping

- a-shuffling

At a 1970 football ground, in the North or elsewhere, you were equally likely to meet skinheads – or as my Grandma called them, “skinnyheads”. This movement too had grown through the second half of the Sixties, as a working-class reaction against the Beatnik generation (the early 70s skin was a different beast to the early 80s revival skin). Your skinhead also liked soul: but he (or she) was just as likely to be into mod music, ska, reggae and dub. Sartorially, a 1970 football skin would be wearing, not bags but a stylish version of the clothes his father wore – jeans, big boots, shirts, cardigans. And probably a Crombie or a sheepskin, and scarves. It could get cold on the terraces.

- skins and beatniks

- football skins (Newcastle Chronicle)

- sartorial skins

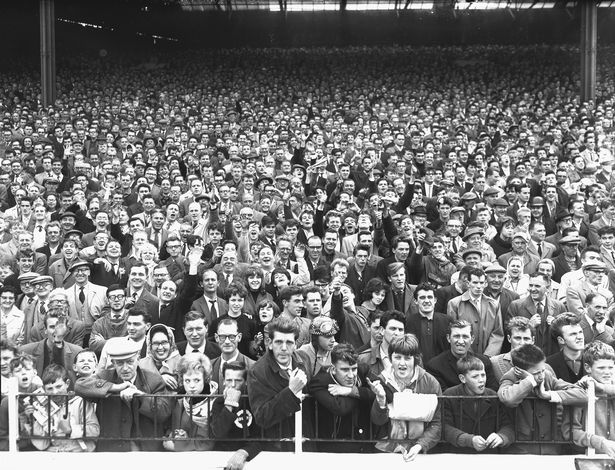

So on that day in 1970 our ingredients are two great teams, soul boys, skinheads, a graveyard, a pretty hefty crowd of 35,908 – and the Boothen End. The Boothen was Stoke’s home end, and, following the etiquette of the day, it was incumbent on Leeds’ more adventurous followers to try and “take” it. Now, “taking” shouldn’t be applied literally. The Boothen held 11,000 and you’re never going to capture that. What the situation demanded, and what a few hundred Leeds attempted, was to get in and stay there – despite, as usual, the best attempts of the home fans to dislodge them.

In the context of 70s football this was pretty routine stuff. Grounds, even at the top level, were effectively unsegregated and crowd trouble was increasingly common as away travel became more popular and accessible. While far from organised, a combination of osmosis and a set of unwritten rules meant those who were interested usually found one another. It’s important to contextualise: out of that 36,000, no more than a few hundred would have been remotely interested or affected. But that was no consolation if you were caught in the middle.

And that day on the Boothen, something went wrong.

The following recollections are from www,oatcakefanzine.proboards.com :

“Well before segregation it was often that the bigger clubs’ followings got in the ground first and took the space behind the goal. It was then up to the home fans arriving later to take their own space back. This happened that day, and Stoke fans got behind the Leeds fans and surged forward crushing the ones at the front against a barrier. The barrier broke and it was very lucky that no one was more seriously hurt.”

“I remember it , I was only eight at the time and I was sitting on the paddock wall behind the advertising hoardings. I remember injured people sitting all around the perimeter track being attended to by St John’s or the police. I have a feeling the game carried on but could be wrong. I remember when we got home my gran was fretting because it had been on the news.”

“My brother broke his collarbone in this incident.”

“In those days you would get other fans in the Boothen. Most would get run out before kick off but the likes of Chelsea, Liverpool and a few more took a bit more removing. You would have to get both sides of them and some of the real hard men would infiltrate their ranks, then with the cry of “oh all together, oh all together” it would all kick off. The day of the Leeds match I think it had been bubbling up all day. The Leeds fans had bricked the Wharf Tavern before the match and this was a bit of a revenge mission.”

“I was against the barrier and was buried up to my chest by people falling on me when it went, I lay there for what seemed like minutes hardly able to breathe. I can still remember it as though it happened yesterday. Luckily I was pulled free and just suffered bruises from being trampled on.”

“This incident gave rise to the famous “Ooh watch the barriers, Ooh watch the barriers” chant that carried on for a few years thereafter.”

“I was at the match as well, but was in the Stoke End. It just looked like normal shenanigans from where I was, but when I got home after the match the folks were relieved I was in one piece.”

“Yes, the Leeds fans were crushed and the barrier gave way. A few had to spend time in N Staffs Infirmary and were photographed, which appeared on the Sentinels front page….Leeds skinheads with black eyes and bruises smiling from their hospital beds.”

“I was 8 and standing near to the back of the Boothen on the left hand side for this game with my uncle, and I remember being pushed and shoved a few times myself so we moved right over to the wall by the side of the Butler Street Stand and watched events unfold. There was scuffling and pushing and surging, and eventually loads of people ended up on the floor with others trampling over them and loads and loads of chaos and noise.

We didn’t know what happened until we got home but those Leeds fans were very very lucky that day.”

“I was one of those Leeds fans on that photo, big thanks to the nursing staff at the N.Staffs hospital and to the copper who saved my life. I am truly lucky to be alive today. One item of clothing was missing for 2 days – my string vest, later found embedded in my chest!”

“I was there in the Boothen that day….very close to where it happened. It was one of the first games I’d ever been to and I remember my uncle lifting me up putting me on a stanchion for most of the game. All I can remember is a couple of surges from Stoke fans towards the Leeds fans, then some terracing opening up with a load of people on the floor. I didnt realise how bad it was until I got back home.”

“I was right where it happened. I had arrived early to get a good viewing point near the Butler Street stand. The Leeds supporters moved up tentatively, looking around from side to side, to take up that rear section of the Boothen to one side of me. The Stoke mob assembled later on the other side at the centre of the Boothen End not long before kick-off. As the game got going, some Stoke supporters drifted over in threes and fours to the other side of the Leeds mob where I was standing. There was no more than thirty Stoke supporters now pushed up against a small cordon of what I could only describe as young, still wet behind the ears, rookie coppers. The Stoke supporters were taking liberties that they wouldn’t normally take with hardened experienced policemen, by jeering, spitting and shoving against the police cordon.”

“The young coppers just didn’t know how to deal with them. Arresting or removing any of the protagonists would have weakened their ranks too much so as to leave a hole, so they just tried to hold out against them. The pushing and shoving led to the small Stoke mob forming a wedge between the rear wall of the Boothen End and the line of coppers, and then the pushing got worse. My rib cage was bursting. The considerably larger Leeds mob below had compacted and moved a little forward with no where to go. Then suddenly it all kicked off to the cries of ‘Ooh all together – Ooh all together!’ ”

“The police could barely raise their arms to get the Stoke lads back and it was the ones right at the back against the wall (who the coppers couldn’t get to) who were really doing all the pushing. Then, like the turning of a rugby scrum, the Leeds mob surged forward and everywhere around just rumbled and shook. There were screams and yelling. The barriers buckled and broke with the first wave of Leeds supporters falling forward onto the walkaway two or three feet below, to be then trampled by the rest of the mob that followed. The cries of desperation and fear resonated all around as the rearmost terraces above the tunnel just shook and rumbled like an earthquake.”

“The mayhem was truly frightening and something I’ll never forget.. It would have been no surprise if people had been killed in the crush. For the next half hour stretchers and people were carrying the injured out and down into the tunnel for treatment. It wasn’t too long after that when the police decided to prevent any away supporters from going onto the Boothen End.”

There’s an excellent but disturbing photo of the terrace and buckled barriers post-collapse, and an injured Leeds fan, in Simon Lowe’s book Stoke City: A Nostalgic Look at a Century of the Club.