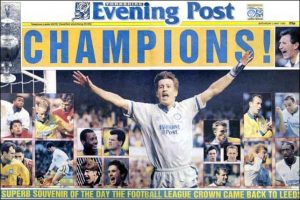

LS92 concludes the generation-spanning storyline begun by LS65 and Bournemouth 90. Like both predecessors it’s loosely contextualised by a seminal Leeds United season, in this case 1991-92 which – as many of us will remember – ended with Howard Wilkinson’s side unexpectedly winning the club’s first title since 1974.

Anyone familiar with the first two books will have a good idea what to expect. Recurring themes abound, principal among them the idea that ill-considered actions sometimes have disproportionately serious consequences. This isn’t a particularly happy thought to plant in anyone’s mind; Morris, whose understanding of backstreet culture and grasp of criminal psychosis feel sharper than ever, plays upon it mercilessly. Fast-paced narrative and periodic shocking violence create genuine tension and excitement.

No one could ever doubt that Morris lives and breathes Leeds. His earthy portrayal, however, suggests he’s unlikely to be offered a job by its tourist board any time soon. Random local references abound; seemingly casual mentions of the New Penny, Waterloo and Fford Grene are in fact anything but. There’s presumably some wistfulness involved here. We all miss now-vanished pubs that smell of fags and have “a long corridor, small rooms off to left and right and a bank of payphones on the wall”.

Alan Connolly is the glue that binds all three books together. His unfinished business drives LS92’s plot, albeit vicariously; this gives Morris free rein to explore new levels of depravity and introduce ever more sophisticated torture methods. The characters we remember so well from Bournemouth 90 are still – unfortunately for them – its victims. Like many others they cannot yet escape the casual brutalism of Connolly’s three-decade long legacy.

French assassin Le Renard provides one gloriously erratic exception. His particular ghosts feel complex and far darker. He quickly develops from two-dimensional stereotype into something way more multi-layered that left me variously appalled, fascinated and sympathetic. That last emotion may seem odd; nevertheless, the crazed hitman’s encounters with various confused pensioners, jobsworths and village idiots would try anyone’s patience.

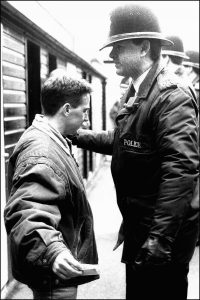

The clueless police are also darkly comic. Bournemouth 90 treated them less than kindly; their portrayal here takes ridicule into darker territory. Know-all plain clothes man Andy Barton now comes over as more corrupt than gullible, framing anyone and everyone to secure promotion by convincing sceptical superiors that organised hooligan gangs still exist. None of this has been remotely overstated. Anyone who watched football regularly during the early 90s will personally have witnessed equally provocative tactics.

Le Renard links the terraces with gangland, despite ironically having little patience for either (Connolly also carried off this ambiguous role with some style). Football does, however, give him some hope of personal salvation; the book accordingly develops into a race between that – increasingly remote – possibility and his accelerating decline into complete madness.

Psychological drama works best when it says little. Morris’ clipped, journalistic style is ideal for describing the tormented mind of someone who has – through combined circumstance, accident and design – lost all feeling bar the most animal of instincts. Analysing Le Renard would be pointless; his confused, hedonistic relationship with the world as he lapses into self-destructive lunacy denies interpretation. Instead we nervously wait for him to commit one final, climactic outrage. There’s something strangely compelling about its intended victims being the stilted occupants of Lee Chapman’s couch.

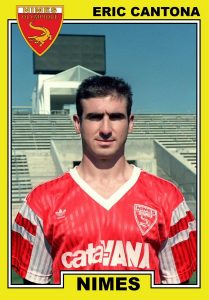

Eric Cantona’s slightly bewildered cameo ironically mirrors his Leeds United career. At just 18 starts (plus 10 appearances as substitute) this was far shorter than many people might imagine. LS92’s narrative begins twenty-four hours before he signed permanently from Nimes; little footballing action features, which isn’t surprising because Leeds played just three times in the ensuing two weeks.

Cantona – notorious in France for petulant behaviour and occasional acts of aggression – didn’t seem typical of players usually favoured by the notoriously disciplinarian Wilkinson. He nevertheless proved inspirational. His flair and presence illuminated the season’s closing stages, adding extra midfield guile exactly when most needed. Le Renard’s neurotic pursuit of him around a Roundhay pizza restaurant merely adds bizarre incongruity to this rebellious glamour.

It would be easy to treat football as peripheral in this fast-paced thriller. Such is not, however, the Leeds United way. Wilkinson’s side massively over-achieved during 1991-92, and the generation of fans who missed out on Don Revie’s era finally had something to celebrate. “Winning ’League would be massive after all ’shit years”, remarks Young Sutcliffe to Neil Yardsley at Bramall Lane. “Shit players, shit away grounds, shit managers. I was even too young to go away in the 80s when at least you lot had a laugh every week.”

The 3-2 win over Sheffield United – and Manchester United’s capitulation to Liverpool later that same day – backdrop a suitably dramatic finale. Morris understands classical unities well enough, and manages to bring the book’s tangled threads together in his usual clinically efficient fashion. There will be none of the loose ends here that so noticeably left LS65 and Bournemouth 90 open to their eventual sequels; ghosts have finally been laid, not least Revie’s eighteen-year-old spectre.