Switzerland 1 Netherlands 4

UEFA Women’s Championship

Sunday 17 July 2022

Euro vision

The context

Kieran and I bought tickets ages ago for four women’s Euros matches. We had already seen last Saturday’s 2-2 draw between Switzerland and Portugal at Leigh, an entertaining game characterised by zealous if slightly frenzied attacking play. This final Group C fixture found us once more watching the Swiss. They needed to win; one point, meanwhile, would be enough for injury-hit holders Holland.

The history

Bramall Lane started off by staging cricket. County games were played here from 1855 onwards, and Yorkshire would remain regular visitors until 1973. Football arrived seven years later – a Lancashire cotton famine benefit game, featuring Sheffield and Hallam – with international matches not far behind. Staging the 1889 FA Cup semi-final between Preston and West Brom eventually persuaded Sheffield United cricket club to try their hand at football. This new team would win the FA Cup in 1899, defeating Derby County 4-1 at Crystal Palace.

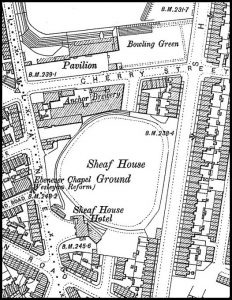

Sheffield Wednesday – then simply The Wednesday – had been Bramall Lane’s previous tenants. Their first ground stood near the Thornborough Road/Myrtle Street intersection some distance further south. They subsequently occupied Sheaf House stadium, behind Anchor Brewery on Cherry Street (the Sheaf House pub marked one corner of this substantial but basic arena, which was demolished in 1909 to make space for a skating rink).

beer is best

The Anchor Brewery (gutted by German bombs in December 1940) was run by Henry Tomlinson and would reputedly give off noxious fumes whenever Yorkshire’s opponents batted. Many other factories surrounded the cricket field’s sooty patch of green. Wardonia cutlery and razor blade works stood on Countess Road; John Richdale’s Britannia Brewery crowded up against Bramall Lane’s junction with John Street, opposite the Cricketers pub.

That same air raid left United’s pitch heavily cratered. Archibald Leitch’s John Street stand (whose ornate, gabled structure dated from 1901) suffered badly; the Kop lost its roof. Both were subsequently rebuilt, but 1920s covered terraces at the Bramall Lane end lasted rather longer. Their eventual double-decker 1966 replacement featured a seating tier held up by thick concrete pillars which seriously impeded the views of standing spectators.

Multi-sport use had long defined the ground’s layout. Football and cricket – whose respective pitches overlapped by twenty yards – perched on opposite sides. This arrangement didn’t really suit either; as Simon Inglis observed, “The Pavilion was too far from the soccer pitch, the John Street Stand too far from the wicket.” But many still mourn United’s controversial 1971 decision to evict their tenants and end more than a century of top-level cricket in Sheffield.

The last County match took place between Yorkshire and Lancashire during August 1973. A new cantilevered South Stand – built by the same company as Hillsborough’s North Stand, and recognisably influenced by it – then covered the former outfield. Leitch’s well-proportioned 1900 pavilion was left in lonely isolation before eventually being torn down to provide additional car parking.

The journey

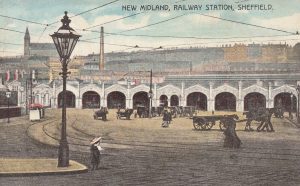

Neither Snake nor Woodhead felt advisable in peak tourist season. I chose the longer (on paper) M62-M1 option instead, which got me there unexpectedly early. Fans – the cheerfully herbivorous mix that was already beginning to characterise this tournament – streamed away from Midland Station and roosted placidly around Sheaf Square’s piazzas and cafes. Devonshire Green’s bombsite memorial had been hosting Holland’s oranje thousands; their game against yellow-shirted Sweden seven days ago must have looked like the aftermath of a highlighter factory explosion.

The thermometer nudged above thirty degrees as I parked behind London Road’s takeaway mile. High-viz jackets buzzed around road-blocks on John Street, where purple-sweatshirted UEFA volunteers – with boxes of flags and clackers – swarmed busily. No-one seemed keen to offer me any souvenirs. This was one of those occasional summer days when high temperatures cause intense media excitement; the main entrance basked quietly, and there seemed little sense that a major international would soon be taking place.

The ground

Both John Street and Bramall Lane stands open straight onto narrow pavements. United fans – looking down supercilious noses at Hillsborough’s suburban location – are keen to remind you that their ground is right in the city centre. Two sides nevertheless feel surprisingly spacious, and that vanished cricket pitch is the reason. Extensive perimeter walls allow you to appreciate fully its original extent; corporate guests’ cars line up where the pavilion used to be, while open land behind the Kop once held practice nets.

- squeezed

- angular

There are still echoes of past times here, not least the South Stand’s deceptively retro profile. Sheffield’s two major grounds share more architectural features than many care to admit. Here – as at Hillsborough – the Kop reminds you of a film set’s two sides; smart modern seating perches on the original banked mound, behind which fans enter via elevated steel balconies and uncovered stairways. The Bramall Lane stand opposite has been remodelled but retains its predecessor’s squeezed, angular profile.

Flesh and wine

Underemployed stewards patrolled outside the Railway. Three people were sunning themselves on dining chairs, and I settled down by the narrow front bar’s gently whirring fan – amidst five decades’ United memorabilia – to people-watch. Diverse punters ambled sedately through; one French journalist talked with me about his national team’s chances before he disappeared outside, clutching a packet of Gitanes.

The landlady dealt ruthlessly with bourgeois customers who complained at having to queue. “You should come on a proper match day”, she remarked. This air of subverted normality was also evident at Man Friday’s chippy on Shoreham Street, whose empty shop and full hot cabinet was scandalously ignored by self-conscious hipsters drinking coffee next door. Its obliging proprietress crammed my double-decker fishcake and battered sausage inside buttered bread; the man behind me loudly admired her deep-fried beefburgers.

The game

Our tickets were in the John Street stand. Kieran turned up just as I finished my fishcake beside the turnstiles. Once inside – past the by now familiar stewards with scanners – we found ourselves surrounded by passionate Dutch followers. Their accompanying band stood a few rows in front, while two friendly Blades fans behind us provided local input and tactical balance.

Lively sparring characterised the first half. Holland’s Daphne van Domselaar tipped Sandy Maendy’s drive just over, while at the opposite end Gaelle Thalmann denied Jackie Groenen, Geraldine Reuteler and Ramona Bachmann. Many felt Lineth Beerensteyn should have had a penalty when Thalmann seemed to bring her down after twenty minutes, but outrageously protracted VAR deliberations decided otherwise.

Holland scored from a corner three minutes after the break when Ana-Maria Crnogorcevic headed neatly through her own goal. This lead, however, lasted only until Bachmann played Reuteler through to neatly equalise. Coumba Sow should then have put Switzerland ahead but two Dutch substitutions proved decisive, Romee Leuchter’s looping header restoring their advantage before Victoria Pelova toe-poked home from close-range two minutes later. Leuchter added the fourth in injury time.

Teams and goals

Switzerland: Thalmann, Maritz, Calligaris, Buhler (Kiwic 57), Aigbogun (Sterli 58), Walti (Mauron 83), Crnogorcevic, Maendly (Folmli 58), Sow (Xhemaili 72), Reuteler, Bachmann. Unused subs: Marti, Rinast, Peng, Humm, Friedli, Riesen, Terchoun.

Netherlands: Wilm, van der Gragt, Nouwen (Casparij 64), Janssen, Groenen, Spitse, Roord (Pelova 64), van de Donk (Egurrola 96), Martens (Brugts 74), Beerensteyn (Leuchter 74). Unused subs: Weimar, van Dongen, Jansen, Dijkstra, Olislagers, Lorsheyd,

Goals: Switzerland: Reuteler 53. Netherlands: Crnogorcevic 49 og, Leuchter 84, 95, Pelova 89.

Attendance: 22,596.