Crystal Palace 2 Huddersfield Town 0

Premier League

Saturday 30 March 2019

The context

One of a fast diminishing number of League grounds left to visit. John and I had seen Palace over the years at more away games than many of their own fans, but getting tickets here became difficult after they got promoted in 2013. Indifferent form – and visitors who were all but down – now proved our salvation.

The history

Welcome to SE25. We’d somehow imagined Croydon would evoke Terry and June’s avenue, or Captain Darling representing the Gentlemen at cricket. Reality proved rather less idyllic. Today’s bland conurbation slinks hopefully around greater London’s more sophisticated coat-tails, emulating only its least likeable features; one of the few truly historic buildings left, Reeves’ Furniture Store, was destroyed by rioters in 2011.

Things used to be very different. Victorian Croydon’s population increased fourteen-fold in just sixty years, with 250,000 people living locally by the time Britain’s first international airport opened at Purley Way. Workers from the Trojan motor plant shared these quiet suburbs with City stockbrokers, attracted to the town because of its convenient location between London and Brighton.

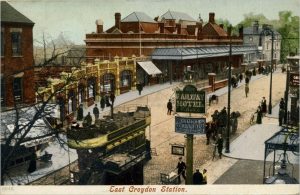

Four railway stations soon opened. The first was named East Croydon. Extension platforms – known as New Croydon – then became necessary, and handled London Bridge services until South Croydon’s new terminus could be built. Suburban passengers mostly traveled via West Croydon; eminent composer Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, whose house was at nearby Aldwick, collapsed there in 1912 and subsequently died.

The town’s growth led to constantly increasing demands on its infrastructure. East Croydon would be extended several more times; six substantial platforms were eventually built, servicing hundreds of trains every day. More recent redevelopment has sadly swept away all trace of some elegantly simple station buildings designed by noted railway architect David Mocatta.

Croydon Aerodrome was fortunately treated with greater respect. Surviving buildings include a control tower, hotel and the terminal building from which Imperial Airways passengers once flew to four continents. 100,000 people saw Charles Lindbergh’s visit with Spirit of St Louis in 1927, while Amy Johnson later began her epic flight to Australia here.

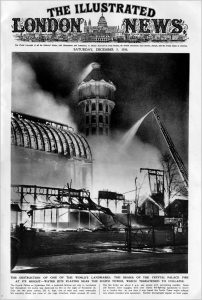

Grand public spaces catered for residents’ leisure time. Crystal Palace Park had been laid out during 1851, named after Joseph Paxton’s enormous cast-iron framed gallery – relocated to Penge Common following the 1851 Great Exhibition in Hyde Park – whose massive windows contained 300,000 panes of glass. It stood among extensive public gardens boasting a concert hall, maze, ornamental lakes and more than thirty life-size dinosaur models.

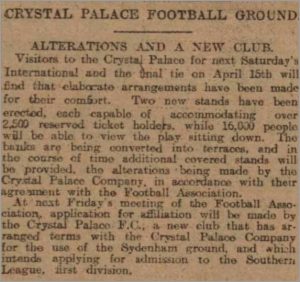

Football also arrived. When Kennington Oval’s modest capacity led eventually to the 1893 and 1894 FA Cup Finals taking place away from London, astute local businessmen recognised that big money could be made by staging these lucrative matches. They redeveloped a natural bowl-shaped arena – where the National Sports Centre is now – which hosted every Final between 1895 and 1914. Its record attendance of nearly 122,000 saw Aston Villa beat Sunderland in 1913.

Three small seated stands were provided but facilities for ordinary spectators left much to be desired. Most fans stood on sloping grass that soon became muddy in wet weather, while many couldn’t even see the pitch. A new professional club, also called Crystal Palace, offered regular football to affluent local residents and eventually became members of Division Three (South).

The Palace spectacularly burned down in 1936. Its eponymous team were no longer there, having reluctantly moved out when Crystal Palace Park was taken over for military use during World War I. They initially rented Herne Hill Velodrome, then took over defunct amateur side Croydon Common’s former ground beside the London to Brighton rail line.

Herne Hill’s cycle track has been in more or less constant use since 1891. Five-figure crowds once turned up to race meetings, and world records would be set here during the 1948 Olympic Games. A basic stand was built, but – as at White City, Catford, Paddington, Stamford Bridge.and other London circuits – most spectators watched from oval-shaped banking.

Their next home offered even fewer refinements. Earth mounds surrounding its cinder running track were known as “the jungle” because of high overhanging bushes, while many fans preferred to watch games from Selhurst station because a platform ticket worked out cheaper than ground admission. Railway maintenance facilities now cover this site; some historians believe one building there incorporates the former main stand.

Selhurst Park dates from 1924. Famous football ground architect Archibald Leitch sold Palace his lowest-budget model – four thousand seats, three open terraces – which subsequently changed little until chairman Arthur Wait built another stand opposite in 1969. Construction was Wait’s trade and he could often be seen labouring on the project himself.

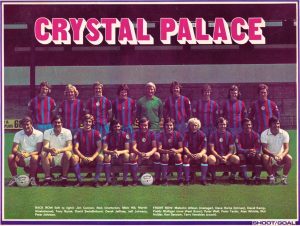

This structure witnessed some exciting times for Palace. Playboy Malcolm Allison – fresh from an abortive spell in charge of Manchester City – introduced new red and blue colours, replaced their traditional Glaziers nickname with the altogether more sexy Eagles but also oversaw two relegations. His 1975-76 Third Division side reached that season’s FA Cup semi-final, losing against eventual winners Southampton at Stamford Bridge.

Allison’s equally retiring successor Terry Venables won two quick promotions. His attack-minded 1978-79 Second Division champions blended older players such as Gerry Francis, John Burridge, Dave Swindlehurst and Mike Flanagan with youth products – Paul Hinshelwood, Jim Cannon, Jerry Murphy, Peter Nicholas, Kenny Sansom, Billy Gilbert, Vince Hilaire – leading to them being rather optimistically dubbed “Team of the Eighties” by some London journalists.

Liverpool needn’t have worried. Palace came bottom in 1981, Venables joined QPR and unpopular new chairman Ron Noades sold most of the team at knock-down prices. He also flogged off half Selhurst Park’s Whitehorse Lane End to Sainsbury’s. This had previously had been a substantial two-storey terrace; the resulting supermarket development truncated it almost beyond recognition.

The journey

Stations triangulate Selhurst Park but going by train wasn’t practical today. We therefore booked a drive to park on and faced urban Surrey’s infamous traffic. This grey corner of a leafy county feels cut off even from the rest of London; even so, everything went smoothly enough until I reversed over someone’s rockery and got fined £90 after forgetting to pay the Dartford Crossing toll.

The ground

We have a well-established routine when visiting any new ground. Arrive early, take some pictures without too many people about, settle down at the nearest pub till kick-off time. Not here. Photography is tolerated at most places – and actively encouraged by bigger clubs – but for some reason South London’s high-vis fraternity mistrust it with zeal bordering on the pathological.

Stewards intercepted us three times on Park Road. A vanload of police then got in on the act. Having yet again told them what I was doing – even though pointing your camera at something easily visible on Google isn’t exactly criminal behaviour – yet more constables pounced further along Whitehorse Lane, excitedly summoning their sergeant from his control room to quote the Terrorism Act and inspect our phones for suspicious content.

Now I’m all for maintaining law and order. But this interrogation felt – as John remarked mildly when the most sedititious image they found was one of his grandson wearing an Aston Villa bib – rather excessive. Matters concluded in surreal fashion with the sergeant’s vague final query “Are you Jimmy Sirrel?” and his muttered half apology that Selhurst Park “isn’t something people would normally want to take pictures of.”

He did have a point. You can’t actually see very much from street level, because two sides nestle against surrounding hills; some turnstiles along Park Road consequently overlook the ground, while others further down are at roof level. Sainsbury’s invasive superstore smothers its bottom touchline more than ever. The only really distinctive stand – whose overhanging design is suitably beak-like – glowers angularly above Holmesdale Road.

Selhurst’s largest terrace once filled this end. Away fans occupied a wedge-shaped corner next to the side paddock, where things could sometimes get lively if big numbers arrived in town. One particularly notorious fracas ensued during May 1989 when Birmingham City’s irritable travelling support, many wearing fancy dress, halted play for 27 bizarre yet violent minutes.

That Leitch main stand remains in use. A simple frontage has, however, long since disappeared behind temporary offices and other ugly paraphernalia. We watched from Wait’s equally traditional version, where everyone seemed friendly; fans stood up to sing, and unobtrusive stewards mercifully spared us any more ill-disguised harrassment.

Flesh and wine

Tangling with the Met used up thirty irritating minutes. We consequently had no chance to sample any of Thornton Heath’s delightfully tatty fast food shops, but at least managed some welcome supping time at the Clifton on Holmesdale Road. This was a reassuringly tourist-free, no-frills alehouse where I even got called “geezer” by one pleasant local.

The game

Relegation battles don’t often produce flowing football. As Huddersfield had won just three games all season – scoring six goals since Christmas – only one team was realistically battling in this one. The first half generally lived down to expectations, although Palace could have been behind but for a tame Chris Lowe back-post header and alert positioning from Vicente Guaita.

They woke up after half time. Luka Milivojevic’s penalty put them ahead after Juninho Bacuna tripped Wilfried Zaha in the box. Ben Hamer had already saved well from Zaha, whose finishing this afternoon verged on wastefulness; Andros Townsend also came close before Patrick van Aanholt made sure with a crisp cross-shot two minutes from time. This defeat was enough to relegate poor Huddersfield remarkably early in the season.

Teams and goals

Palace: Guaita, Wan-Bissaka, Tomkins, Dann, van Aanholt, Meyer (McArthur 45), Milivojelic, Schlupp, Townsend (Kouyate 80), Batshuayi (Benteke 73), Zaha. Unused subs: Ward, Hennessey, J.Ayew, Kelly.

Huddersfield: Hamer, Smith, Schindler, Kongolo, Durm, Bacuna (Williams 80), Hogg, Mooy, Pritchard (Stankovic 94), Lowe (Kachunga 80), Grant. Unused subs: Coleman, Hadergjonaj, Daly, Rowe.

Goals: Palace: Milvojevic 76 (pen), van Aanholt 88

Attendance: 25,193.