Having only ever read two football novels – one of which, The Damned United, was pretty much factual – I’m not, on the face of it, ideally suited to give an opinion about Billy Morris’ “dark, uncompromising crime fiction” (his words). But the first thing you need to realise about this book is that football’s walk-on part is – at best – secondary to a principal theme of hidden secrets and their eventual, inevitable revelation.

Context also preoccupies Morris. Like many places, Leeds experienced significant change as the Nineties dawned. Not least came a vibrant rave culture and associated organised crime. Smiley, happy people having fun also meant big money for those who sold pills and managed doors; deep-seated Roses territorialism (and its associated violence) was temporarily shelved as bands like The Farm and Happy Mondays brought partisan followings across the Pennines for high-profile gigs.

Many lives are ordinarily insulated by family, socialising and sport. Simple pleasures protect us from uncomfortable truths best left alone. This book is about what happens when our defences fail – and, for protagonist Neil Yardsley and brother Stuart, the consequences prove devastating. Through no particular fault of his own (though being absent while in prison didn’t help) a newly-mature Neil finds himself responsible for life or death situations he never chose but now needs to resolve.

At best Morris’ characterisation verges on genius. Nowhere can this be better seen than in Connolly, the strangely magnetic Rolling Stones-obsessed publican and gangland boss. His combination of childlike pleasure with murderous tendencies is compelling. Despite Glaswegian roots Connolly typifies Leeds, both team and city – “I’ve got us on a minibus with the old LS9 Asylum lads”, he says. “You’re gonna hear some proper tales of going to football in the 70s. We had some real tear-ups.”

Embittered police chief Roger Thorpe runs Connolly close. Obliged to handle a three-day riot when all he wants to do is retire and go sailing, his “f**k you all” mantra will engage many of similar age who have attained seniority in fast-paced careers. Operation Wild Boar was two years ago; matchday tactics had begun noticeably softening post-Hillsborough, and Morris develops this idea by cleverly contrasting “intelligence-led policing” with Thorpe’s old-school truculence.

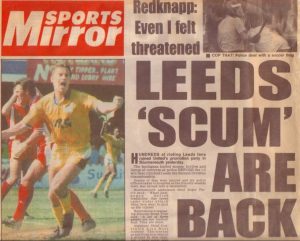

Accurate chronology of that weekend’s mayhem interweaves the fictional drama. First we have thousands of fans, many lacking tickets and some “who hadn’t been to a game since Revie’s era”, heading south on Friday 4 May. Most make for West Cliff; disorder breaks out with police at the Holiday Revival pub, and boozed-up young men – by now thoroughly riled – are dispersed across town. This, as West Yorkshire’s Football Intelligence Unit predicts, is not the smartest of moves and a night of widespread thuggery ensues.

Saturday’s march on Dean Court is redolent of Quadrophenia rather than the pitched battle portrayed by contemporary reporting – lots of running about, some genuine violence but with inept policing more at fault than is usually admitted (Bournemouth fans may, with some justification, hold different views – I’ve nonetheless heard accounts from at least some who don’t). Finally of course comes payback, as belated but substantial police reinforcements reclaim streets and beach. “TSG really going to town on the Northern scum”, gloats Thorpe.

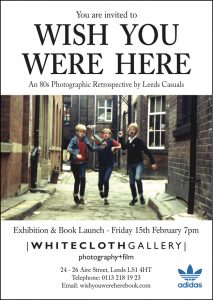

Morris understands Yardsley’s world. His recent interview with footballbookreviews.com saw him discuss growing up locally, a first visit to Elland Road in 1973 (United drew 1-1 with Chelsea) and the Eighties casual movement. Leeds is sometimes unfairly overlooked when football dressers reminisce; it nevertheless rivalled Liverpool and Manchester, as proved some years back by Wish You Were Here at Whitecloth Gallery. “The 80s were a special time”, commented propermag.com . “Working class males started to dress like a cross between Ronnie Corbett and Ivan Lendl whilst stylishly terrorising anyone and everyone who was at the game of a Saturday afternoon.”

You can read the full interview here.

Convicted hooligan Yardsley finds terrace culture increasingly irksome when he comes out of prison. Young Sutcliffe – cocky, vicious, unrestrained – is the new “general”, and 25-year old Neil feels irrelevant and jaded. Events would soon overtake Sutcliffe too. Bournemouth proved almost the last hurrah of large-scale domestic hooliganism; for those who don’t remember and are patient enough to look, Morris’ book illuminates societal shifts which ultimately rendered such behaviour unfashionable.

That long hot weekend was a watershed. By the time 1990-91 began with equivalent numbers of largely peaceful Leeds fans invading Goodison Park, Italia ’90 – for reasons I never fully understood – had worked some strange magic on football crowds. Possibly it was Ecstasy-fuelled, perhaps we all grew up, maybe gentrified new-era fans really did help civilise those of us who thanklessly kept things alive during the previous decade. But times changed irrevocably.

For these reasons and more it’s hard not to look on Bournemouth’s undeniably appalling pillage with at least some nostalgic regret. Before long our familiar, anarchic terraces were replaced by Sky Sports, mercenary players, docile crowds, names on shirts, squad rotation, game management and all the other bollocks. Chief Inspector Thorpe got left behind first; those of us who began watching football in the 70s and 80s soon knew exactly how he felt.

F**k you all.

[Thanks to Billy Morris for the fan pictures used on this page.]