Arsenal 5 Bolton Wanderers 1

League Cup 3rd round

Wednesday 24 September 2024

cannon canon

The context

Somehow neither John nor myself had been here before. Every time it seemed we might, which wasn’t often, tickets proved impossible to obtain. But finally the Holy Grail beckoned – a midweek Cup fixture, average opposition, our own teams already knocked out and limited appeal for home fans with (for once) serious title-winning ambitions.

The history

Controversies define this club. Not least among them is Woolwich Arsenal’s 1913 relocation from one side of the Thames to another. They previously played at the Manor Ground, just north of present-day Nathan Way. Poor crowds – resulting from financial hardship amongst many fans who worked in the nearby munitions factory – brought about both their new name and a rather cynical cross-river move.

Genteel Highbury had expanded during Victorian times. High-density housing spread across open fields; only the protected space of Finsbury Park halted this relentless march, which promptly headed west towards Holloway Road instead. Arsenal successfully tapped into a working class population eager to watch football every other Saturday. Crowds doubled overnight, and by 1932 the average gate exceeded 40,000.

Kings Cross was just three miles distant. A substantial engine shed – with adjacent freight sidings – had been built near Belle Isle, where the Great Northern line looped around to pass beneath Regent’s Canal. This provided stabling for dozens of locomotives. Tightly-packed lines filled all the available space between here and York Way, while passenger services travelled through tunnels beneath. Many railway workers began supporting their new local team.

Shed and goods yard closed in 1963 after declining for many years. Nyloned-up prostitutes wearing second-hand Soho heels no longer haunt Goods Way; the whole vast site has now been redeveloped. British Rail built a new depot just south of Finsbury Park station, which remained operational for barely two decades but was popular among railway enthusiasts because of its resident fleet of Deltic diesels.

Arsenal became members of Division 1 after the Great War. No-one knew exactly why or how – a sixth-place finish in 1915 hardly merited promotion – but well-connected chairman, Sir Henry Norris, was widely presumed to have exerted his considerable influence. They soon became known as “the Bank of England club” and made Herbert Chapman Britain’s best-paid manager.

Chapman had been banned from football when Leeds City were found guilty of illegally paying players. He successfully appealed, took over at Huddersfield and led them to a FA Cup win followed by two First Division titles. His deep-lying team exemplified counter-attacking football, breaking quickly from defence with fast wingers who played accurate passes across the penalty area.

Nine eventful years cemented Arsenal’s lasting legacy. In addition to tactical brilliance – captain Charlie Buchan quickly assimilated offside law changes, and devised a 3-4-3 formation perfect for counter-attacking play – Chapman wasn’t above deploying sharp practice or occasional backhanders. These strategies worked; his greatest side successfully emulated Huddersfield, winning both the 1930 FA Cup and successive championships.

There seemed no end to Chapman’s creativity. He introduced a controversial forty-five minute clock, numbers on shirts, experimental floodlighting and even had London Underground rebadge Gillespie Road station as Arsenal (Highbury Hill). This quietly suburban stop featured attractive red-brick Leslie Green detailing; it was nevertheless ruthlessly modernised so that more supporters could be accommodated on matchdays.

Three more Leagues and another FA Cup were secured before World War II broke out. When Chapman died prematurely in 1934 he left behind a blueprint for the modern manager, fully controlling club matters without boardroom influence. His successor George Allison went one step further; coaches Joe Shaw and Tom Whittaker ran team affairs, while showman Allison effectively became director of football.

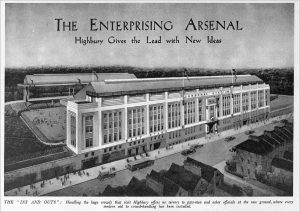

Highbury was also redesigned. It originally resembled many other Archibald Leitch new-builds, one substantial stand with extensive banked terraces. This trusted formula ensured London’s biggest capacity. But growing prestige demanded facilities to match, and Chapman’s relentless drive initiated sweeping changes that began with a magnificent new West Stand.

Engineers had traditionally built football grounds. Arsenal innovated by securing the services of acclaimed architect, Claude Waterlow Ferrier; his bold design, producing two near-identical stands, combined Thirties elegance and neat functionality. The West – hemmed in by houses – could only really be seen from inside Highbury, but its counterpart on Avenell Road featured an imposing Art Deco facade with lavish marble interiors.

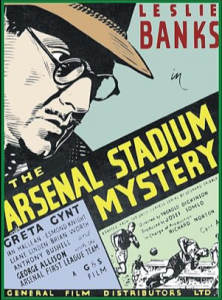

The last official game before World War II took place on 6 May 1939. This provided footage for Thorold Dickinson’s matchday poisoning whodunnit, The Arsenal Stadium Mystery. Leslie Banks starred as Detective-Inspector Anthony Slade; Allison had a small speaking part, while various players – notably Eddie Hapgood and Cliff Bastin – also made cameo appearances. Visitors Brentford represented fictitious amateur opponents The Trojans.

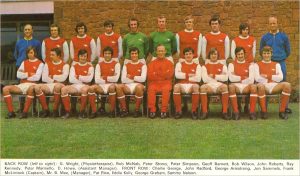

Arsenal’s longest barren spell spanned eighteen post-War seasons. They won no trophies between 1953 – when Whittaker delivered their record-breaking seventh Championship – and 1970. Club physio turned manager Bertie Mee ended this run when his disciplined, resilient side won the Fairs Cup before achieving a first-ever League and Cup double in 1970-71.

This triumph capped six years’ steady progress. Mee had revitalised Arsenal, successfully partnering military-grade administrative skills with coach Don Howe’s more modern methods. Experienced signings – Bob Wilson, Bob McNab, George Graham, George Armstrong, Frank McLintock – perfectly complemented the homegrown talent of Ray Kennedy, Charlie George, Pat Rice, Peter Simpson, John Radford and Eddie Kelly.

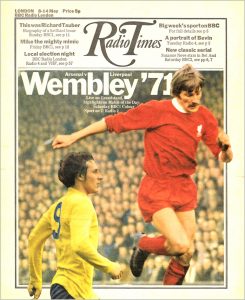

George’s famously prone celebration following his extra-time Cup Final winner against Liverpool became a defining 1970s moment. For me it satirises the supposed weariness of footballers who played way above their individual talents, went 21 games unbeaten at home and battled Leeds for every point. Mee taught his teams to thrive on adversity; of all Arsenal’s many triumphs this still feels the most significant.

The journey

We certainly didn’t want any hold ups today. Light southbound traffic saw us reach our rented parking space near Tollington Park by mid-afternoon. Making it back home afterwards would have been awkward, so I booked into the Premier Inn at Cannock. Clear skies and open roads – apart from a niggly small-hours diversion around Warwick – got me there just after two.

The ground

Little changed here for five decades. The extended North Bank – behind houses on Gillespie Road, where Stadium Mews is now – had become Highbury’s popular terrace after Ferrier’s first stand was built. German incendiary bombs destroyed its recently-built roof during April 1941, also damaging Mayfield’s adjacent laundry. This would regularly engulf nearby spectators in clouds of steam during the ground’s early years.

Chapman’s clock eventually occupied a gantry opposite. This banking therefore became known as the Clock End. It never lost Leitch’s original 1913 profile, although some incongruous corporate boxes eventually provided partial – if incidental – cover for fans standing underneath. Access was only possible from Avenell Road, meaning that Arsenal enforced strict segregation much later than many other clubs.

62,000 people saw Chelsea’s visit during the Double season. But – even with a smart new two-tier North Bank – post-Taylor Report capacity fell so dramatically that only 38,000 seats could be squeezed in. Demand for tickets increased still further when Arsenal won two further doubles, and with expansion of Highbury proving impractical they began considering alternative sites.

Ashburton Grove recycling centre seemed most suitable. Dustcarts had once deposited Islington’s rubbish here; Arsenal were obliged to fund 2300 homes, provide another waste facility and construct two vast bridges across the Moorgate-Finsbury Park commuter line. Designer Christopher Lee described their imposing new ground as “beautiful and intimidating.”

Expensive flats have been built into and around Highbury’s two listed stands. As a consequence it remains very much unspoiled. That handsome Art Deco frontage still adorns Avenell Road, while the equally ornate West Stand hides as ever behind Victorian villas on Highbury Hill. Gillespie Road station, meanwhile, oozes suburban vibes despite serving thousands of fans before and after every home game

The Emirates Stadium’s impressive capacity is still much less than Highbury at its peak. But – despite surprisingly similar dimensions – everything seems far more spacious. Uncluttered surroundings help create this illusion, as does an elevated situation between two converging railway lines. The old clock has been preserved high above one smoked-glass frontage, while self-consciously 1930s-style branding adds quiet dignity that modern stadia don’t often possess.

John and I mooched thoughtfully around both grounds as sudden rain cleared the streets. Many people have – quite reasonably – contrasted Highbury’s elegant period charm with its unashamedly consumerist replacement. But football simply reflects social forces. If fans today enjoy souvenir shopping more than shouting, will pay over the odds for tickets and don’t mind being used as polyester sandwich boards, then who are we to argue?

Flesh and wine

We wasted no time settling down at the Eaglet on Seven Sisters Road. This was a classic London street-corner boozer that had been bombed by Zeppelins during World War I. With John as designated driver our early arrival left me happily unrestrained; things got even better when I spotted a nearby samosa stand, and my simple heart positively overflowed to discover that the landlord didn’t mind people bringing in takeaway food.

Our long pre-match session made Arsenal’s uniformly bland concourse facilities feel tolerable enough. No decent ale, of course, but they did sell small bottles of wine; the obliging attendant decanted three into a pint glass to make me look edgy. Pie and mash – with very Northern gravy – was also on offer. This unsurprisingly turned out quite unlike anything Harry Tate would have recognised.

The game

Mikel Arteta had decided to try out some young players. Bolton therefore resembled a herd of cattle being plagued by wasps. Every Arsenal goal capitalised on hesitant defending; this was certainly true of their opener from Declan Rice, who slipped two markers and swept in Josh Nichol’s square pass. Teenage debutant Ethan Nwaneri added another just before half time when he slid onto a probing Raheem Sterling centre.

Nwaneri’s decisive second punished Chris Forino for his lazy crossfield ball straight at Nichols. Bolton belatedly woke up; a solo goal from Aaron Collins, finished expertly after rounding sixteen-year-old ‘keeper Jack Porter, would be the night’s best moment. But Arsenal remained solid and Sterling soon pounced again following some byline trickery from Bukayo Saka, with Kai Havertz – who was quickest to react when Luke Southwood spilled yet another Arsenal shot – volleying acrobatically home.

Teams and goals

Arsenal: Porter, Lewis-Skelly (Magalhaes 62), Calafiori (Kacurri 70), Kiwior, Nichols, Rice, Jorginho, Nwaneri, Sterling (Kabia 81), Jesus, Saka (Martinelli 71). Unused subs: Heaven, Fedorushchenko, Saliba, Partey.

Bolton: Southwood, Toal, Ricardo, Forino (Johnston 71), Williams, Dempsey (Matete 69), Sheehan, Arfield (Thomason 69), Dacres-Cogley, Collins (Charles 79), McAtee (Adeboyejo 78). Unused subs: Baxter, Inwood, Matheson, Schon.

Goals: Arsenal: Rice 16, Nwaneri 37, 49, Sterling 64, Havertz 77. Bolton: Collins 53.

Attendance: 59,056.