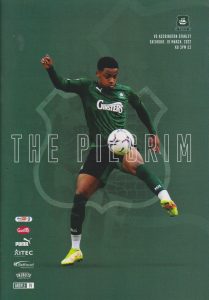

Plymouth Argyle 4 Accrington Stanley 0

League 1

Saturday 19 March 2022

green man

The context

Today would level John and myself up on eighty-seven League grounds each. Home Park – which I last visited thirty years ago – was a new one for him. We had almost made the long journey several times before, been thwarted by Covid in spring 2020 and just not fancied it several times since. Decent weather combined with light pre-tourist season traffic now gave us the opportunity to put matters right.

The history

Going to Plymouth interweaves my childhood memories. Dad (ex-Royal Navy) had family there, and we returned often on family holidays. I grew up associating its football club with three things; Paul Mariner, a cheerfully home-made zoo beneath one corner flag and marauding, flare-clad young men in green scarves who invaded Exeter every season. Only the latter institution has survived.

Adult trips here generally drew the paternal warning “Don’t go down Union Street.” So of course I always did. This half mile-long road – connecting city centre to dockyard – was long notorious as the West Country’s Ayia Napa, offering red light attractions along with no fewer than 100 pubs and clubs. Little survives now that modern slum clearance has effectively finished what Hitler’s Luftwaffe began.

Plymouth’s first bomb fell on Swilly, the sprawling council estate (these days called North Prospect) that neighbours Home Park. Enemy raids during spring 1941 later devastated dockside districts such as Devonport, Millbay and Stonehouse, along with most of the city centre; post-War reconstruction saw what little remained replaced by grid-style American blocks. One broad, windswept thoroughfare runs from a rocky seafront to North Road railway station. Only Union Street remains from the Victorian road layout.

Argyle’s record seasonal goalscorer is (perversely) a distinguished ex-soldier. Jack Cock – 32 goals from just 37 appearances during 1926-27 – joined the Footballers’ Battalion during World War One, rose to Sergeant-Major’s rank, was posted missing presumed killed and won medals for bravery. Good looks combined with stage experience (he sang in music halls throughout his playing career) brought him two film parts, The Winning Goal (1920) and The Great Game (1930).

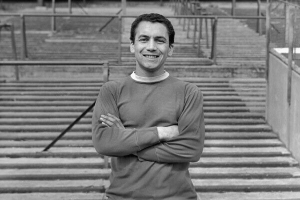

Jack – along with brothers Donald and Herbert – had started at Brentford. He arrived via Huddersfield, Chelsea and Everton, later joining Millwall. Another Cornishman, Mike Trebilcock, began his League career with Plymouth but became famous for two comeback goals during Everton’s 1966 Cup Final win against Sheffield Wednesday. This afforded him cult status on Merseyside despite only ever making eleven appearances there.

The journey

Seven hours from Preston, broken at Sedgemoor (site of the last battle on British soil. Motorway services were militarily important during James II’s reign). We left John’s car down a quiet side street facing Outland Road just after one. It was bright and sunny, with early arrivals already hanging around in that aimless grazing way fans have nowadays. Avoiding the big official car parks would prove wise; swift footwork had us headed back north just twenty minutes after the final whistle.

The ground

Houses went up locally after World War One, replacing open farmland. Central Park’s rolling open spaces – which now separate the football club from Peverell and Mutley – also date from then. It’s Devon’s largest park, despite various schemes nibbling away at the original 94 hectares that Lord St Levan donated to improve health among local residents. Incongruous post-match scuffles still occasionally take place among children’s playgrounds and herbaceous borders.

Home Park suffered badly from wartime bombing. Incendiaries intended for nearby Devonport Docks hit both pitch and grandstand, burning the latter down. A smart new version went up in 1952; the double-decker Mayflower Stand – complete with faux Archibald Leitch balcony – perched behind substantial terraces, taking overall capacity above 45,000. More seats (and eventually basic executive boxes) were later added to its dark, low-roofed rear section.

- exposed

- shop

This venerable but increasingly decrepit structure survived until four years ago. The replacement stand looks very similar, not least because an extensive paddock area still lacks any sort of cover. Respect for history is all very well; leaving several thousand seats exposed to Plymouth’s notoriously wet climate does, however, seem rather careless. Several old turnstile blocks have been preserved, including one that one now accesses Argyle’s club shop.

- nestles

- partisan

Sitting with Stanley fans felt sensible today. Tickets, though, proved elusive. Passive-aggressive locals in the booking office queue finally took pity, and we found ourselves directed – through lines of stewards who insisted on carrying out full body searches – to a single open visitors’ turnstile overlooking Central Park. Winding, hedge-lined steps once led down behind open terracing here; despite late 1990s reconstruction the ground still nestles comfortably in its leafy – yet disconcertingly partisan – surroundings.

- Barn Park

- Lyndhurst

- Devonport

[Bob Lilliman]

A continuous horseshoe-shaped roof has obliterated the three distinct standing sections previously known as Barn Park, Lyndhurst and Devonport. These names now identify blocks of anonymous green seats. The north-eastern quadrant – favoured by Argyle’s noisier fans, who roost there to taunt away supporters – is called Zoo Corner, evoking poignant summer holiday memories in those of us old enough to remember.

Flesh and wine

Pasties were my bottom line today. I found plenty in the Ivor Dewdney van parked conveniently outside Central Park’s wrought iron gates. Dewdney’s nine local shops underline Plymouth’s thriving pasty culture; Argyle’s shirts advertise another “oggie” maker, while Royal Navy personnel nicknamed Devon people “guzzlers” because of their liking for them. The naval base is known colloquially as “Guzz” to this day.

I had heard about a nearby working men’s club that supposedly welcomed discreet visiting fans. Although it appeared deserted determined door-knocking – and judicious charity donations – soon secured honorary membership. After happily supping until two-thirty, we walked back up the hill to join two hundred Lancastrians huddled in lonely isolation among 4,000 netted-off seats.

The game

Argyle started in fourth place, but mid-table Stanley looked most dangerous early on as Michael Nottingham headed a Sean McConville cross against the crossbar. Both sides defended languidly; Panutche Camara took full advantage when he tidied up Danny Mayor’s deflected centre, while Joe Edwards combined well with Conor Grant before volleying smartly past Toby Savin.

Even though Accrington did plenty of attacking they fell further behind when substitute Niall Ennis – picking up James Wilson’s pass – drove his low cross-shot beyond Savin. The unfortunate goalkeeper then found himself sent off after coming out to clumsily intercept Ryan Hardie. Goalscoring opportunity was the decision; harshly so, because the striker’s push on Stanley defender Mitch Clark somehow went unpunished. There would be no way back now, and Hardie’s glancing header beat teenage substitute Liam Isherwood for Plymouth’s fourth.

Teams and goals

Plymouth: Cooper, Wilson, Bolton, Gillesphey, Edwards, Mayor (Broom 80), Houghton, Camara (Randell 65), Grant, Hardie, Garrick (Ennis 61). Unused subs: Sessegnon, Burton, Jephcott, Crichlow.

Accrington: Savin, Clark, Sykes, Nottingham, Rodgers (Isherwood 69), McConville, Pell (Adedoyin 57), Butcher (Coyle 45), Hamilton, Longelo, Bishop. Unused subs: Conneely, Morgan, Amankwah, Lewis.

Goals: Plymouth: Camara 12, Edwards 37, Ennis 64, Hardie 79.

Attendance 13,076.