Aston Villa 2 Leicester City 4

Premier League

Saturday 4 February 2023

The context

My previous visit here came some time ago, a First Division game against Luton watched from the still-terraced Holte End (Tony Cascarino scored Villa’s goal in their 2-1 defeat on 9 March 1991). Thirty years’ absence seemed remiss; also, John and I had decided to chase down the four League grounds we were yet to visit together, and this – his own team – would be first.

The history

There’s another piece about Villa – principally describing my experiences there – elsewhere on this site.

Aston’s story begins with the Holte family. Originally from nearby Duddeston, Sir Thomas Holte built Aston Hall between 1618 and 1631 after winning favour with James I. Civil War skirmishes subsequently damaged his new home; it’s now a museum, situated amidst extensive public parks. These – laid out by unemployed local men after World War One – used to be considerably bigger before the A38 Aston Expressway obliterated their eastern section.

Foul fanzine from 1976 characterised city planners as “pulling down huge areas of terraced houses and building motorways over their remains.” Aston Hall gardens narrowly escaped the fate of many humbler local premises, and this gem of local history was fortunately – unlike much of Birmingham – preserved. Villa Park had originally been part of Aston Lower Grounds, a Victorian funfair; its name, like that of the Holte End, came about through popular usage rather than via any official decision.

Villa’s new ground had one ornate stand – on Witton Lane, built over former tropical gardens – and a banked cycle track. Leitch’s masterpiece Trinity Road Stand dated from 1922. Both would ultimately end up destroyed by crass, if pragmatic, acts of vandalism; the latter survived longest but was scandalously demolished in 2001. I still fail to understand how those responsible got away with it.

Twin terraced ends – Holte and Witton – achieved broadly equivalent size during the 1940s. Their giant banking underpinned Villa Park’s impressive size and secured three 1966 World Cup games. The former later gained partial cover; its neglected counterpart fared less well, being replaced by the unlovely late-seventies North Stand’s executive boxes, inadequate standing provision and woefully isolated seating tier. The replacement Witton Lane roof (1962) had been equally unimaginative.

Fans best remember the Holte. This truly was enormous, at one time able to accommodate over 30,000 and rivalled only by the South Bank at Molineux (Hillsborough’s extended mid-80s Kop also achieved similar scale). A central barrier allowed segregation for FA Cup semi-finals. Dingy concrete undercrofts and dusty upper reaches – the whole ground used to be caked in characteristic Birmingham grime – perfectly enhanced its dystopian elegance.

If this place could talk it would describe many things. Victorian chairman William McGregor founding the Football League isn’t one, because Villa (after initially using a pitch in Aston Park) spent their first nine League seasons at Wellington Road in Perry Barr. By then they had already claimed three of their seven League titles; another three soon ensued, along with six FA Cups, as George Ramsay created his intricate passing side the “Perry Barr Pets.”

Villa’s 1981 League title and the European Cup success that followed are equally defining memories for fans of our generation. Passing years – half a lifetime now – haven’t diminished them. No club will ever be champions again using just fourteen players; they combined perfectly, and then shrugged off the loss of manager Ron Saunders to hold things together for one more glorious season. Even for fans of other teams there was something refreshing (if slightly irritating) about all this.

Things unravelled in 1982-83. Villa’s preliminary round home leg with Dynamo Bucharest took place behind closed doors, following crowd trouble during the previous season’s semi-final against Anderlecht; they eventually lost home and away to Juventus. Applying hindsight, three prestige exhibition games either side of Christmas – the World Super Cup against Uruguayan side Penarol in Tokyo, and two European Super Cup ties against Barcelona – disastrously stretched a tiring squad.

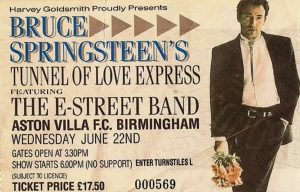

Fifty-five FA Cup semi-finals took place here between 1901 and 2007. Villa Park also staged the 1999 Cup-Winners’ Cup final between Lazio and Real Mallorca. Its central geographical position suited everyone, as did a capacity that peaked (post-World War Two) at over 75,000. Other attractions came too; Bruce Springsteen’s two concerts in June 1988 were so loud that they could be heard ten miles away.

triumph

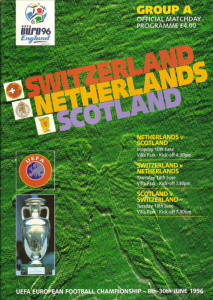

Euro 96 became the old place’s modern triumph, with three Group A games – featuring Holland, Scotland and Switzerland – followed by the Czech Republic/Portugal quarter final. Holland eventually saw off brave Scottish resistance, going through on goals scored despite their 4-1 defeat to group winners England at Wembley. Noisy, good-natured Dutch fans thronged Birmingham, while newly-seated Villa Park – dominated by a huge new Holte End stand – also seemed freshly colourful.

The journey

Birmingham roads confuse me, so as this was John’s patch I left the driving (and navigation) to him. My youthful trips to Villa were all done on the stopping train from New Street’s easternmost platform (calling at Duddeston, Aston, Witton, Perry Barr, Hamstead, Bescot and Walsall). Coppers would try and stop you getting off at Aston; I was adopted on my first visit by some much older Wolves fans, who blagged themselves and 15 year old me off its elevated platform and into the nearby Swan & Mitre.

This line formed part of the Grand Junction Railway between Birmingham and Warrington. Victorian planners originally wanted a mile-long tunnel beneath Aston Park; the Hall’s tenant objected, necessitating today’s sweeping but circuitous route. Vauxhall station – later Vauxhall & Duddeston, now simply Duddeston – became Birmingham’s first terminus. The booking hall was rebuilt post-War after being badly damaged by German incendiaries.

Two branch lines began at Aston. One to Stechford still survives, while a freight spur serving Windsor Street depot closed in 1980. Aston depot stood between Holborn Hill and Nechells Park Road. This could accommodate sixty locomotives on twelve lines, reaching peak efficiency during the immediate post-War years. Its facilities proved surplus to requirements when diesel supplanted steam; the site is now buried beneath houses and industrial buildings.

Today’s arrival was straightforward enough. We parked up early at Birchfield School (our spot by the exit would prove invaluable later on) and wandered down Trinity Road towards Villa Park. This is an inner-city ground, surrounded on three sides by tightly-packed streets; park and Expressway make it seem deceptively open from the fourth, but our walk today featured unrelenting urban scenery broken only by occasional patches of wasteland.

The ground

Modern Villa Park has achieved scale at the expense of grace and charm. Witton Lane was shifted over to accommodate the tidy but egotistical Doug Ellis Stand, meaning dozens of houses had to be demolished; another giant stand opposite completely oversails Trinity Road. The Holte, meanwhile, occupies a far larger footprint than seems strictly necessary. Much of this comprises elaborate exterior staircases and faux-Victorian architectural conceits.

I can’t completely explain why this seems wrong. Perhaps it’s because that 1990s frontage unsuccessfully imitates the old Trinity Road design of elegant red brick and stained glass. Replacing something so beautiful with an inferior copy feels crass at best; needs must, but the old facade could and should have been saved. Rangers (among others) have shown how new roofs and extra seating can be added without throwing away history in the process.

The North Stand won’t be with us much longer either. Villa recently announced ambitious rebuilding plans. Few people would want it preserving; in some ways, however, this archetypal late-Seventies construction has plenty going on. The stand seriously overstretched club finances, involved dealings dodgy enough to necessitate police involvement and even now exudes faded glamour. These are truly things we should remember.

Flesh and wine

A familiar story. Fanzones and concourse drinking are steadily crushing private enterprise around Villa Park; this allows the club to grab ever more money from people who really should know better. We scorned such shallow pursuits, instead following one purposeful-looking gang of blokes who had that unmistakeable headed-for-the-pub spring in their step. Sure enough they led us round several corners, along some anonymous streets and into the Sacred Heart.

Bouncers here multitasked as car-park attendants while several hundred fans thronged maze-like bars and function rooms. Such clubs used to be commonplace near football grounds. Their hospitality spans generations; so do match-going traditions among the families who use them. Sacred Heart Church dates from 1897, having been built to serve Aston’s immigrant Irish population. I thought of Dexy’s Midnight Runners’ My Life In England:

“I can remember St Theresa’s Social/When Kevin Barry rang out/And Mum whispered to me “Kevin, in England this song is not allowed.”

Chips and curry fortunately were, the bar served them and I managed to negotiate myself a bonus sausage as well. Happy days.

The game

Today’s visitors found themselves fighting relegation. Villa had been underachieving as usual but were free of any such worries, and went ahead soon after kick off when Emiliano Buendia hit Leicester’s bar from distance and Ollie Watkins neatly placed the rebound. This lead didn’t last long. James Maddison equalised – a good finish, set up by shambolic dithering from Boubacar Kamara – before another Watkins shot pressured Harry Souttar into putting through his own goal.

Buendia soon rattled the bar again as it became apparent that neither team could defend properly. Leicester pulled level through Kelechi Iheanacho’s diving header, and then took the lead just before half time. Their goal came after the hapless Kamara once more fumbled in midfield. Four outpaced defenders played new Brazilian signing, Teté, onside; he was lightning fast and rounded Emilano Martinez expertly.

Villa came back out determined to level. Substitutes Alex Moreno Lopera and Philippe Coutinho tightened up defence and midfield, Coutinho had a goal disallowed for offside (one of nineteen Villa chances overall), Watkins also missed when scoring would have been easier. All this proved costly; things got stretched, midfielders were caught square and another long ball set Dennis Praet free to beat Martinez with even greater flair than Teté had shown.

Teams and goals

Aston Villa: E Martinez, Young (Cash 59), Konsa, Mings, Digne (Moreno Lopera 45), J Ramsay (Coutinho 45), Kamara (Dendoncker 82), Douglas Luiz, Buendia, Bailey (Duran 82), Watkins. Unused subs: McGinn, Chambers, Olsen, Sinisalo.

Leicester: Ward, Castagne, Souttar, Faes, Kristiansen (Thomas 81), Tielemans, Dewsbury-Hall (Mendy 67), Cardoso Lemos Martins (Soyuncu 83), Maddison (Praet 67), Barnes, Iheanacho (Vardy 67). Unused subs: Daka, Iversen, Brunt, Marcal-Madivadua.

Goals: Aston Villa: Watkins 9, Souttar (og) 32. Leicester: Maddison 12, Iheanacho 41, Cardoso Lemos Martins 47, Praet 79.

Attendance: 42,055.