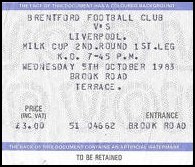

Brentford 1 Liverpool 4

Milk Cup, 2nd Round, 1st leg

5 October 1983

The context

Fans mourn when a ground closes. In the case of Brentford’s departure from Griffin Park the sense of loss was keenly felt, deepened by lack of a proper goodbye and shared by many who had visited while supporting other teams.

So why was it popular? Lazy journalists obsessed about the famous pub on each corner, but (while doing all four boozers before a match enlivened many a day out) that wasn’t the whole story. Location may also have been a factor. David Robins comments in We Hate Humans on the number of neighbourhood teams in the capital, and the likes of Brentford, Orient and QPR undoubtedly offer a unique blend of community spirit and metropolitan edge. But the real reason is simply that this was a good place to watch football. The ground might have been cramped in later days but for many years its extensive terraces and modest crowds offered excellent views in a comparatively relaxed atmosphere.

Griffin Park was the product of halcyon times. A 1927 Cup run funded the Main Stand on Braemar Road and further work during the 1930s saw the ground’s capacity grow as manager Harry Curtis assembled Brentford’s greatest ever team. A record attendance of 38,535 watched the First Division game with Arsenal in 1938, and for a few glorious years the Bees gave the top sides a run for their money. But World War II put a stop to this expansion and the club spent most of the next seven decades knocking about the lower leagues. By the end its life the ground could accommodate just 12,000 fans and was inadequate for what had lately become a second-tier set up with serious aspirations to once more play at the top level.

Curtis came to Brentford from Gillingham. He was a former referee and therefore a rarity in coaching circles. Director Frank Barton offered him the position at Griffin Park almost at random because the two were cronies from refereeing days (Curtis had presumably been forgiven for sending off defender Alf Capper on a previous visit). At the height of their pre-war dominance Brentford were able to attract internationals Dave McCulloch (Scotland), Idris Hopkins and Dai Richards (Wales) and Billy Gorman (Eire) to West London, while Billy Scott and Les Smith debuted for England, Les Boulter for Wales and Duncan McKenzie and Bobby Reid for Scotland. But when Curtis finally left in 1949 the club were back in Division 2 and on a downward trajectory.

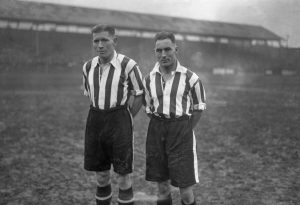

They still had the odd day in the sun. Jim Towers and George Francis – the Terrible Twins – racked up 300 goals between them during the Fifties. Both were products of a scattergun youth policy introduced by manager Alf Bew after Brentford fell into Division Three (South) in 1954. The two were friends both on and off the pitch, did National Service together and were sold as a pair to Third Division rivals Queens Park Rangers when the board panicked after a poor 1960-61 season. Neither prospered at Loftus Road. Towers soon moved on to Millwall and then drifted into non-League football via Gillingham and Aldershot. Francis, meanwhile, played just twice and found himself back at Griffin Park within a year.

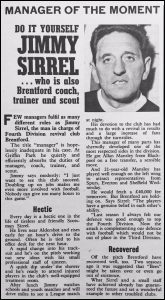

Brentford’s upstart neighbours became something of a nemesis in the years that followed. Long-serving boss Malky MacDonald had spent heavily in an attempt to win promotion, but despite this the team were relegated into Division Four in 1966. As the club began to lose money hand over fist chairman Jack Dunnett entered into private negotiations with his friend, QPR owner Jim Gregory, and hatched a plot in which the Bees would be liquidated so that Rangers could sell Loftus Road for housing and move into Griffin Park. Needless to say this didn’t go down well with the fans. Ructions ensued that only ended when supporters’ association chair Peter Pond-Jones and shoe magnate Ron Blindell brokered a new regime to depose Dunnett and manager Billy Gray. Trainer Jimmy Sirrel was put in charge of team affairs and things began to improve.

Sirrel did a valiant job. He kept his team in the top half of the table despite having a small squad and being largely reliant on loan signings. Finances, too, were more stable. But trouble was never far away and the spring of 1968 saw another bizarre scheme emerge, this time a groundshare at Hillingdon FC’s Leas Stadium. The proposal would have seen a change of name to Brentford Borough and the club’s persistent debts wiped out by the sale of Griffin Park. It was a panacea solution that would probably have ended badly. The Bees, however, were fortunately spared having to find out. Another last-minute loan saved them and Sirrel gradually built a promotion-chasing side before departing for Notts County in October 1969.

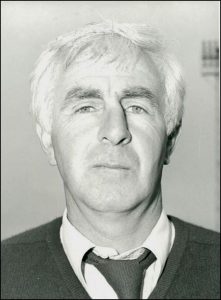

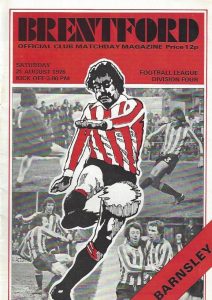

His replacement was Frank Blunstone. The former Chelsea outside-left had been on the Stamford Bridge coaching staff since 1964 and took Brentford to another level, reinforcing the existing squad with shrewd signings in key positions that enabled them to reach the Fifth Round of the FA Cup in 1971 and win promotion the following year. But keeping the team in Division Three proved beyond him and getting it back there was too big a task for successors Mike Everitt and John Docherty. The eventual saviour turned out to be Bill Dodgin junior. His father Bill senior had managed the club through an equally difficult spell in the mid-Fifties – now, under the 47 year-old’s guidance, the Bees were promoted in 1978 and waved goodbye to the bottom division for a prolonged spell.

That promotion season is here recalled on brentford-mad.co.uk .

“Growing up living in Richmond and attending school in Ealing meant getting the 65 bus every day. It also gave me a free bus pass to use on Saturdays – so in autumn 1977 I went to watch Brentford for the first time with a couple of friends. They played Halifax Town and won 4-1. Stevie Phillips scored two goals including a penalty and we went away sharing the joy of the other home fans. My next game was when Brentford played Folkestone in the first round of the Cup. Phillips scored twice again and Brentford won 2-0.

I went four times again that season. Brentford beat Crewe 5-1, Torquay 3-0, Rochdale 4-0 and Stockport 4-0. In six games at Griffin Park, I had seen Brentford score 22 goals and Stevie Phillips had got nine or ten of them I think.”

Griffin Park

Brentford have always been unpretentious. Another contributor to the same site describes it this way:

“I’d visited other grounds – Stamford Bridge and Loftus Road in particular – and seen First Division teams grind out dull 0-0 draws as I sat seemingly miles from the action. Brentford was different. You could stand in this fabulous old terrace (the Royal Oak End) which seemed to echo former glories. And when the Bees were attacking the other end you could scarper down to Ealing Road; like the teams, changing ends at half time. All this and goals galore. Since then I’ve never really understood why anyone wants to follow the so called glamour teams.”

The Royal Oak End stood on Brook Road South flanked by two of the four pubs, the Royal Oak and the Griffin. These were late-Victorian buildings whereas the pair at the Ealing Road end dated from 1841 (the Princess Royal) and 1853 (the New Inn). Until 1904 the land between Braemar Road and New Road had been an orchard owned by brewers Fuller, Smith and Turner. Their griffin emblem was was adopted as the name of Brentford’s new ground when the Bees moved here from Boston Park. The Griffin pub became the team’s headquarters. The Princess Royal also did service as club offices between the wars and it was here that Harry Curtis accepted the post of secretary-manager in 1926.

Griffin Park remained essentially unaltered until a fire broke out in the Braemar Road stand on 1 February 1983. Midfielder Stan Bowles saw flames from his nearby house as he did the washing up (no doubt in characteristically maverick fashion) but by the time he raised the alarm two-thirds of it had been destroyed. This was the first in a rapid series of events that changed things for ever. Next the wooden terrace extension at the rear of the New Road side failed to survive the Popplewell Report, then in 1986 the venerable old Royal Oak End was demolished to make way for a block of flats. Land behind the open Ealing Road terrace had also been sold for housing, hemming in the ground on all four sides at precisely the same time as capacity fell by more than half. This unfortunate coincidence would eventually seal its fate.

The stand’s damaged section was rebuilt in a functional and jarring style that left it as effectively two stands. A fascia hid the join from view but when viewed from above and behind the deception was plain to see. A minimalist structure replaced the old terrace. This became known as the Wendy House, featured a tiny seating tier over an even more miniscule standing area and meant it was no longer possible to walk from one end of the ground to another. The rear portion of the New Road side was never used again. Initially the void was fenced off with corrugated iron and later on the 1930s roof was replaced by a narrower version and seats added, leaving the concourse and original supporting girders open to the sky. Terracing survived to the last at both ends.

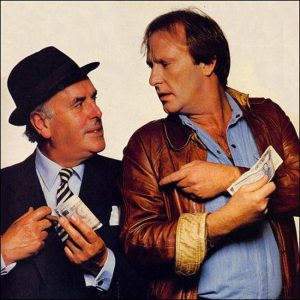

Griffin Park features in two black and white films, The Winning Goal (1920) and The Great Game (1954). These gave acting debuts to Chelsea striker Jack Cock and the Bees’ own Tommy Lawton (who had by then left for Arsenal). But arguably the ground’s finest moment was an appearance in Minder that inadvertently recorded the final days of its 1930s configuration. The Long Ride Back to Scratchwood features Arthur Daley’s disastrous venture into ticket touting, a plot in which Terry’s friend Justin visits footballer “Benno” Benson during a training session at Griffin Park. It includes extensive footage of the Royal Oak End and, poignantly, the southern section of the Braemar Road Stand which burned down between the episode’s filming and its broadcast.

This is a place that created many memories. Here are a selection from travelling supporters who retain lasting impressions from their visits.

“My first and only trip was in the 1976/77 season. As a student I was on a one month Inter-Rail holiday with two mates. On the Thursday before the game we were in Oslo. We were scheduled to go home on Saturday but I’d miss the match. After agonising a while I thought ‘bollocks to it’ and got on the train two days early on my own. After a multitude of trains through Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Germany, Holland, Belgium and France, and the Calais-Dover ferry, I finally arrived in London on Friday evening and crashed at a mate’s house. On Saturday I ended up at Griffin Park. Worst match ever, we lost 2-0 and had a bloke sent off.” (Barnsley, via barnsleyfc.org.uk )

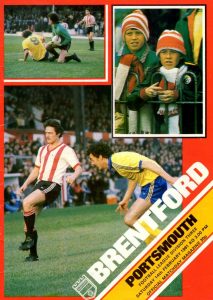

“I grew up reasonably close to Griffin Park (well, about half an hour away in Woking) and my Dad’s mate was a season ticket holder. On a few occasions he’d lend the ticket to us if he couldn’t go and if Dad and I weren’t off to see Sunderland. As they had the same kit and colours I used to wear my Sunderland bobble hat and scarf to the match. One Sunday afternoon they had Brentford as the featured game on The Big Match. We were watching it and they zoomed in on me, dressed in my hat and scarf, and Brian Moore said something about Brentford being a family club and always being good at encouraging kids to support them.” (Sunderland, via readytogo.net )

“Went for a midweek game in the late 80s/early 90s. Raining hard and from the outside it looked like the away terrace had no roof. As I was in a work suit I went in the home terrace but then realised there was a bit of roof for away fans. Got the police to walk me round the side of the pitch. As I approached the away end, flanked by two coppers, all the nutters started applauding.” (Bristol City, via otib.co.uk )

“I lived in Brentford for 31 years. The games we played there were great for me. Leave home at five to three, back home at quarter to five. One evening after I drove home from work I was getting out of the car and my missus said “Paul, Roman Abramovich is in the garden.” Now it’s not often you hear that, but it was true. I lived in Mafeking Avenue, an “L” shaped road behind the road leading to Griffin Park. Lots of people thought you could walk down the long bit of the road to the corner and cut through to the ground, but you just cut through in to the gardens. A minute later Roman came past me with two very large gentlemen, one each side. At that time Chelsea were playing their reserve games at Griffin Park.

Another memory was the day they played Portsmouth at home. I was on my way to the High Street and there at the end of the road was a minibus full of Pompey fans. Now I don’t like being late to games myself, but it was 8am! They said they were going to ‘make a day of it’. In Brentford? Good luck with that, I thought.” (Bristol Rovers, via gaschat.co.uk )

“A game that really sticks out is the Autoglass game around 1995. It was surreal. I remember a Chelsea fan called Phil from work coming, he asked what sort of crowd was expected and if many Fulham were going? I said about 1500 with maybe a couple of hundred of us. We took a half day and got in the New Inn about 1 where we got stuck right in to the beers. Fulham fans were coming in all afternoon and I remember Chelsea Phil saying, blimey every Fulham fan going must be in here tonight.

When we staggered out of there we walked down New Road and on turning the corner saw a massive queue snaking up and down the road. I was stunned. A few police and stewards were trying to control the crowd saying Brentford had opened one away turnstile as they only expected a smattering of Fulham fans. Got into the ground 15 mins after kick off and the away end was packed, not like the restricted number they let in now but proper rammed. It was an edgy steamy atmosphere in there and when Nick Cusack scored via a major ricket from their ‘keeper the end went mental. I think the crowd was about 3500 and at least 2000 were from Fulham.

One of my Brentford mates ended up getting a slap on the New Road terrace when a few Fulham started kicking off in there. He hated Fulham anyway but has detested us since that night.” (Fulham, via friendsoffulham.com )

The game

Fire damage was still evident when Liverpool arrived for this tie. Although the floor and roof of the stand had been rebuilt the dressing rooms underneath hadn’t, obliging both teams to change in portakabins behind the Ealing Road End and trot across a car-park and down the terraces to reach the pitch. Brentford manager Fred Callaghan had injury problems and so his 39 year-old assistant Ron “Chopper” Harris found himself facing the champions and Cup holders. Midfielder Terry Hurlock was also missing, with strikers Tony Mahoney and Keith Cassells only passed fit to play shortly before the game. To everyone’s surprise it was Mahoney who went into the side for his first appearance since the previous December.

Callaghan had been an accomplished full-back so it was ironic that his Brentford team were notable for attacking prowess and defensive frailty. Mahoney, Gary Roberts and Francis Joseph thrived on the creativity and bite of Bowles, Hurlock and Chris Kamara in 1982-83 but a back line that conceded 50 times away from Griffin Park told its own story. Paddy Roche, Alan Whitehead, Terry Rowe, Tony Spencer and Graham Wilkins leaked goals as fast as the forwards could create them and an injury to Mahoney ultimately kept the Bees in mid-table. Even so, the club saw little transfer activity in the summer other than the arrival of goalkeeper Trevor Swinburne from Carlisle and a misguided attempt to replace the recently-retired Bowles with Reading’s Terry Bullivant.

Early exchanges tonight were all about the strikers. Joseph and Michael Robinson competed to see who could miss the most chances until eventually Robinson set up Ian Rush with the opener. Joseph, not to be outdone, played in Roberts for an immediate equaliser but Liverpool upped things after the break. First Robinson converted Craig Johnston’s cross to put them back in the lead, then three minutes later Souness – dominant in central midfield – hit a firm shot past Swinburne that effectively ended the game. Rush completed the scoring shortly before time when he pounced on yet another cross from the industrious Johnston. Mahoney, meanwhile, quickly faded and hobbled off with a recurrence of his leg injury.

Nearly 18,000 watched the match. Griffin Park would never again host a crowd this size, not least because mid-1980s reductions in capacity would render it impossible. Liverpool attracted their lowest-ever attendance for the second leg when 9,000 diehards turned up at Anfield to see them win 4-0.

Revisited

These pictures show Griffin Park awaiting the bulldozers. Brentford fans were cheated of a proper farewell by the Covid 19 pandemic and (save for a handful of ghost games played behind closed doors) the match against Sheffield Wednesday on 7 March 2020 proved its last.

- playing bridge

- New normal

- Princess diary

- super store

- Braemar games

- modernised

- utilised

- heraldic

- headquarters

- housing

- wasted

- underused

- exposed

- light show

- abandoned

- rebranded

- redundant

- reclaimed

- neighbours

- nobility

The Bees’ new home is a mile away, next to the Chiswick Flyover and squeezed into an unpromising site triangulated by railway lines. Exchanging one cramped place for another seems illogical but Brentford hanker after an all-seater stadium with modern amenities. While the Brentford Community Stadium might not have a pub on every corner (and in fact doesn’t even have corners), the ground’s design is striking and innovative. It isn’t likely to be poached by QPR either.

Teams:

Brentford: Swinburne, McNichol, Rowe, Salman, Whitehead, Harris, Kamara, Joseph, Mahoney, Bullivant, Roberts. Sub: Booker.

Liverpool: Grobbelaar, Nicol, Kennedy, Lawrenson, Johnston, Hansen, Dalglish, Lee, Rush, Robinson, Souness. Sub: Hodgson.

Attendance: 17,858