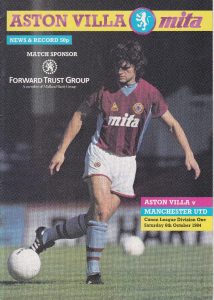

Aston Villa 3 Manchester United 0

Football League Division 1

6 October 1984

The context

The 1984-85 season has gone down in history as the nadir of English football. Which is slightly odd, because most of the time it felt like nothing of the sort. There had of course been some bad hooliganism in 1984 – most notably Luton v Millwall and Chelsea v Sunderland – and 1985 would be the year of Bradford, Birmingham and Brussels. But in the last days of autumn these events were six months off, and few of us particularly saw them coming.

United, under flamboyant Scouser Ron Atkinson – “flash Ron from Old Swan” were on a self-proclaimed mission to end Liverpool’s recent title hegemony. This aim was achieved in 1981, but unfortunately for them it was Villa who won the league under Ron Saunders. Undeterred, and living up to their reputation as the First Division’s big spenders, United had brought in Gordon Strachan from Aberdeen, Alan Brazil from Tottenham and Jesper Olsen from Ajax at a combined cost of £1,500,000. Strachan was a combative midfielder instrumental in Aberdeen’s Cup-Winners’ Cup triumph in 1983, while Olsen was a tricky left-winger fresh from Denmark’s run to the semi-finals of Euro 84.

Saunders missed Villa’s greatest hour, the 1982 European Cup win, having flounced off over a contract disagreement and bizarrely resurfaced at city rivals Birmingham (the equivalent today of Pep Guardiola rocking up at Huddersfield). So Villa’s victory in Rotterdam was achieved under his erstwhile assistant Tony Barton, who remained in charge until May 1984. when his side’s tenth-place finish was deemed unacceptable by chairman “Deadly” Doug Ellis. (Ellis was seen by some as determined to rid Villa Park of the vestiges of the Saunders regime, as its successes occurred during a spell when he wasn’t in charge.)

The history

Picture a Shropshire comprehensive. It is the Games lesson, a five a side tournament is taking place, and in a throwback to the Brian Glover scene in Kes the boys are allowed to “be” the player and the team of their choice. Among those taking part are Wolves (Burridge, Eves, Clarke, Gray, Hibbitt), Shrewsbury (Ogrizovic, MacLaren, Cross, Hackett, Stevens), Telford (Charlton, Mather, Williams, Mayman, Walker), Villa (Spink, Shaw, Withe, Mortimer, Morley) – and the usual Manchester United and Liverpool gloryhunters. “Plastic” might have been a term 30 years in the future, but the phenomenon is nothing new.

Kids at my school tended to watch Telford, Shrewsbury or Wolves – the former because you didn’t have to go far, the other two because they were at either end of the nearest railway line. Telford were on something of a high, having galvanised the town by winning the FA Trophy in 1983 and reaching the fourth round of the FA Cup the following spring. Shrewsbury were a decent second-tier side, with two recent Cup quarter-finals to their name. And Wolves, although in near-terminal decline, had won the League Cup only four years previously.

Uprooted from Exeter in 1982, and therefore well used to the lower end of the football market, I chose the Telford option and dabbled with the others. But mostly I wanted to see West Brom, because they had Cyrille Regis and were exciting and progressive (at least until Atkinson abandoned them for United and took half the players with him). This led me further afield than most of my classmates were comfortable to go. West Bromwich was seen as dangerously avant garde in Eighties Telford, not least because to get there you had to strike out on local buses and trains through areas that were not known as particularly welcoming.

And Villa? Well, most Albion fans at that time hated Villa with a passion (in my experience the particular animosity towards Wolves came later). So being of a contrary disposition I started watching Villa too, to see what all the fuss was about. (We didn’t like Birmingham City much either, but I wasn’t desperate.)

The journey

When I describe a trip to the match these days it’s normally in the context of what the traffic was like, whether the trains ran on time and so forth. In 1984 certain other things needed to be taken into account, not least the need to avoid getting lamped by marauding youths with flicky New Romantic fringes and sta-prest trousers. Having sampled the unique post-match ambience of Rolfe Street station a few times, I started to use the 74 or 78 buses which went right past The Hawthorns. Admittedly you had to catch them from either Wolverhampton or Birmingham, and granted those places could be like warzones depending on who Wolves or Blues were playing. But at least the journey itself was usually quiet.

Villa was a bit different. My favoured route to Villa Park was the “express” bus from Telford to Birmingham, and then the stopping train from New Street station. The stops (which I can recite to this day) were Duddeston, Aston, Witton, Perry Barr, Hamstead, Bescot and Walsall. The little electric train went from platform 1a, the furthermost, dingiest (and therefore most easily policed) corner of that vast concrete labyrinth. You might be sharing your carriage with some pretty lively characters, but on the plus side it was usually too rammed for anything to kick off, and you were on there less than ten minutes.

- 1

- 2

- 3

1 all aboard! 2 concrete labyrinth 3 welcome to Birmingham (Geograph)

As usual I, along with a few other pacifists, chose the long walk from Aston over the short walk from Witton. And as usual the police on the platform tried to shove us back on the train. Having convinced them we weren’t going to Villa (“Match, officer? What match?”) it was a relatively relaxed wander from there, under the Expressway and past Aston Park, to the safety of the crowd and the Holte End turnstiles.

It’s important to be balanced here. The Eighties were violent times, in broader society as well as at football, but even so you could generally go about your business without too much bother. There was probably trouble today but I didn’t see any, unless you count the police happily truncheoning the Villa Youth in the bottom right-hand corner of the Holte, not far below where I was standing. Shouting yes, running around yes, a definite air of menace and apprehension, yes. But hand-to hand conflict? I avoided that, as was usually possible so long as you were careful where you went and who you chose for company.

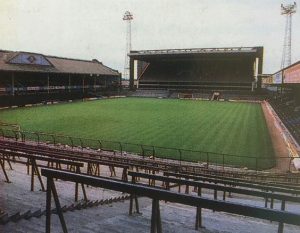

The ground

Although usually spoken of as one of the very best football grounds, I always felt Villa Park in the Eighties had something of the Emperor’s New Clothes about it. The Witton Lane stand, faced by houses from the opposite pavement, was a plain, small and scruffy conversion from a former terrace. The North Stand to its right was more about Doug Ellis’ corporate vision than anything else – although unquestionably modern, two intrusive rows of executive boxes meant the seating tier was too far above the pitch and the terraces below were cramped and offered a poor view. The Trinity Road stand, meanwhile, while architecturally perfect at street level and in the posh seats, had been spoiled by another clumsy terrace conversion to seating. Watching a game from here could be uncomfortable, due to dreadful sightlines and the lack of a roof, and fractious as spectators struggled to see over each others’ heads.

Two things made Villa Park great:

- The floodlight lamps at each end were arranged to spell out A on one pylon and V on the other.

- The Holte.

In an era when many grounds had large terraced ends, The Holte was something else. Capable of holding the population of a small town, its 28,000 capacity made this biggest and best of terraces awesome and scary in equal measure. Villa Park without the Holte End would have been very ordinary. But with the Holte it was a thing apart, a sooty monolith rising above the grimy Birmingham landscape, and the first landmark to be looked for as the “express” bus trundled along the nearby M6.

The Holte was named for the Holte Hotel which stood (and still stands) behind it. From the direction of Aston Station the pub – in 1984 terribly dilapidated, with rough-as-fuck clientele and a dodgy nightclub underneath – was the first thing you saw, at the point where Witton Lane and Trinity Road converged, holding Villa Park – in the words of Simon Inglis – “like a pair of tweezers”.

The roof, built in 1962, angled upwards and covered only the rear third of the terrace. While most of the crowd got plenty of what passed in Birmingham for fresh air, this contrasted with the grim and brutalist concrete undercroft, whose Faustian splendour was crowned by some truly horrifying toilets. By the early Eighties the Holte was split from top to bottom by a central segregation fence. This served little purpose during domestic games but came into its own during the FA Cup semi-finals, which Villa Park hosted most years, allowing two sets of fans to be accommodated at the same time.

- 1

- 2

1 grim and brutalist 2 segregation fence (Heroes & Villains)

Flesh and wine

I don’t know what I ate that day but it was undoubtedly some rubbish or other, and most probably it was a hot dog because they were cheapest. You don’t see many old school hot-dog vendors nowadays (I’m not talking about the kind of hipster “dogs” you get in fanzones either, but the crappy sort that used to be sold from those pop-up stands on street corners). Back in the day no match was complete without a sloppy, tasteless frankfurter on a dry torpedo roll, garnished with watery onions and smothered in ketchup to try and give it some body.

I was 16 when this game took place, an age at which a trip to the football called for two separate and very distinct deceptions. The first was to convince bus drivers and train guards that I was 15. The second was to convince pub landlords that I was 18, because pubs were a useful place to keep warm and out of trouble while one waited for a bus. (It was essential to choose carefully. The Witton Arms was no place to keep out of trouble, as I learned to my cost on more than one occasion.)

We knew favourite Birmingham pubs not by name, but by description. Thus there was “the pub under the ramp”, “the pub like a train” and “the pub under the station” – respectively the Exchange, the Iron Horse and the Market. The first two were on Stephenson Street, behind the Midland Hotel. The Exchange was tucked away under the ramp that led from New Street via the Bull Ring shopping centre, a dark, windowless vault inhabited by unfriendly troglodytic misfits but an excellent hiding place. The Horse, down the road, was fitted out inside to resemble a railway carriage. It was a poky little hole with a seriously abrasive and usually half-pissed landlady.

The Market, on the corner of Dudley Street and Station Street, is the only one still standing, although it’s called something poncy now. It was only OK when Blues weren’t at home (their notorious fighting crew usually hung out around the station – another of their haunts well worth avoiding was the Bar St Martin around the corner. This pub, at the base of the Rotunda, was the ex-Mulberry Bush, one of two boozers bombed by the IRA in 1974). The Market was handy for avoiding a wait in the Midland Red bus station across the road, where the “express” bus dropped off and picked up. This was a cavernous fleapit filled with diesel fumes and fag smoke, which doubled up as a drinking den for large sections of the Birmingham underclass.

The game

Barton’s replacement was Graham Turner. He had been player-manager and subsequently manager of Shrewsbury Town for six years, leading them to outrageous levels of overachievement and establishing the club as a fixture in the Second Division. He should probably have realised his limitations, and Ellis certainly should have done. Before long Villa would be playing League derbies with his old club. But for now he announced his arrival by securing a truly remarkable coup in the transfer market.

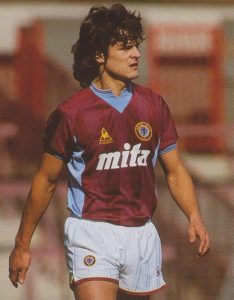

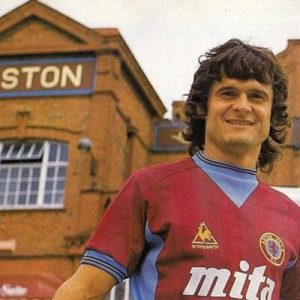

In the days leading up to the game it became clear that Villa’s new player, French winger Didier Six, was expected to make his debut against United. Nowadays it’s hard to imagine the impact big-name foreign signings used to have in the insular British game. The acquisition of Six was seismic. He had played for France in two World Cups, 1978 and 1982, and – like Olsen – starred in the 1984 tournament, which France won. Aged 29 in August 1984, he was at the peak of his powers, with 370 top-flight European appearances and 123 goals behind him. As further evidence of Turner’s acumen Six cost Villa precisely nothing, arriving on a loan basis from Mulhouse.

United were unbeaten going into the match and two points off the top. Villa were nowhere. But this afternoon Six was the difference between them. He gave his marker, United and England centre-back Mick Duxbury, such a miserable time that sections of the press afterwards questioned Duxbury’s suitability as an international. On 20 minutes Six left him for dead to cross Colin Gibson’s long ball perfectly for the lurking Peter Withe. Minutes later it was 2-0, as Allan Evans took advantage of confusion in the United box and placed the ball past an unsighted Gary Bailey.

Six and McMahon ran United ragged that day, and a third goal from Rideout should have been followed by more, as the same player and also Mark Walters missed good chances. Talking later of the dance he led Duxbury, Six recalled “I needed to be clever to not get into contact with him as I wasn’t ready physically. I only had one goal, play simply and clean to gain confidence. Then I tried four or five dribbles.”

You can see highlights of the game here .

.

Teams and goals

Aston Villa: Day, Evans, Williams, Ormsby, Gibson, Birch, Cowans, McMahon, Rideout, Six (Walters), Withe.

Manchester United: Bailey, Moran, Hogg, Duxbury, Albiston, Moses, Muhren, Olsen, Strachan, Brazil, Hughes.

Goals: Withe, Evans. Rideout

Attendance: 37,161