Wigan Athletic 0 Telford United 0

FA Cup 1st round

21 November 1982

The context

Small towns were much smaller in the Eighties. Nowadays Telford is well-connected to the wider West Midlands conurbation, but back then it was far more isolated and – particularly in the small communities randomly designated a New Town in 1967 – almost quaintly insular. We had no motorway until 1983, no nightclubs until 1984 and no local radio station until 1985. Our only newspaper came out once a week.

Despite a futuristic design and persuasive marketing Telford was a depressed (and sometimes depressing) place. Unemployment on some of its 1970s housing estates topped 30%, while the old mining areas – Dawley, Wellington, Madeley – were still surrounded by unlandscaped slag heaps, the ubiquitous “mounts” of a local dialect unchanged since the times of Betjeman’s A Shropshire Lad. Captain Webb the Dawley Man was the nearest thing we had to a local hero until the questionable talents of Carole Decker were unleashed on an unsuspecting world. And even there you had the feeling many of his swimming stunts were carried out on a Friday night after the pubs closed, with a gang of mates egging him on from the bank.

Telford United were neither futuristic nor persuasive. As Wellington Town they’d been longstanding but generally unspectacular members of the Southern and Cheshire Leagues. Their Bucks Head home, in the northern corner of the town, was a substantial if rather decrepit ground dating back to Victorian times. Its alleged 13,000 capacity hadn’t been tested since a 1930s game against fierce local rivals Shrewsbury.

Renamed at the same time as the area (to the severe displeasure of most supporters), three years previously the Whites had been bundled – with other clubs of similar size and standard – into the nascent and snappily-titled Alliance Premier League. This was the much-vaunted point of the newly-conceived semi-professional pyramid. The move elevated Telford to membership of the only national competition outside the Football League.

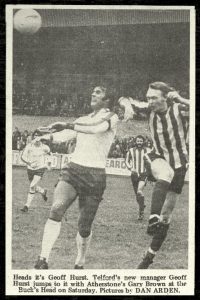

The previous decade had been an eventful time for the team. The marquee signing of Geoff Hurst as player-manager in 1976 raised their profile, and at the end of 1981-82 they applied for election to Division Four. But FA Cup form was poor. United were knocked out in the early stages year after year, a dismal run that included embarrassing defeats to the likes of Caernarfon Town. So no-one had very high hopes when the 1982-83 Cup campaign started with a home win against Buxton. In fact few people took much notice at all until the fourth qualifying stage in late October, when a 3-0 victory over Grantham put Telford into the First Round for only the second time since Hurst lifted the World Cup.

Springfield Park

Wigan themselves were only four years out of part-time football. Elected to Division Four in 1978 in place of Southport, they adapted well and after a promotion the previous spring Larry Lloyd’s side were now rather precarious members of the Third Division. Unlike the team, however, their ground remained decidedly non-League. To those of us who disembarked from Gerald Smith’s buses on that cold November afternoon there seemed little difference between Springfield Park and our own shabby Bucks Head, except that at Wigan the shallow terraces of the away end were bounded by grass banking instead of the cinders we stood on at home.

For big aways – of which this was the first of many – Britannia Coaches used to pick up little huddles of fans at various points around the sprawling town, each with his carrier bag of cans and a newspaper and perhaps some butties for the journey. The drill then was for the coach to travel solo before meeting up with others at a motorway services somewhere en route, then proceeding to whatever grim rendezvous had been dictated by the local constabulary. The road North out of Telford in pre-M54 times went straight along Newport High Street, always an opportunity to hurl abuse and flourish scarves and V-signs at Wolves-supporting local youth. But today it was deserted and the pubs weren’t yet open. Pretty much the only sound on our hung-over coach was snapping ring-pulls and rustling copies of the News of the World.

On the outskirts of wherever we were going a sergeant or an inspector would get on, be greeted with a drunken chorus of “Telford, Telford, Telford” and warn “If you lot don’t shut up I’m turning this coach round and sending you home.” He’d then launch aggressively into a dire list of rules and imprecations, the broad thrust being that if you stepped out of line on his patch you’d be nicked. A variation on this theme was to urge good behaviour because the local fans were “a right bunch of nutters”. After this we would progress slowly through grey local streets, exchanging yet more gestures with local ragamuffins and taking the odd missile, before parking up in another miserable spot where we were ‘encouraged’ to get into the ground before we could cause any bother.

As usual our bus was late leaving and even later arriving, meaning that by the time we were let off outside the turnstiles we’d been treated to a fractious crawl through Springfield’s less than spacious thoroughfares. The single narrow entrance to the car park was imaginatively named First Avenue (no prizes for guessing the name of the next street down). After we’d inched along it to general abuse and sundry acts of vandalism, few had either time or inclination to investigate the Springfield Hotel or any of the other charming hostelries nearby. This was the classic one way in and one way out. Exiting after the game would prove even more eventful.

Springfield Park had been subjected to a visit from Chelsea in the 1981 League Cup. This resulted in a tightening-up of security, but in those days merely having fences in place was no guarantee fans would go where they were meant to. In non-League football people generally stood where they wanted, and here too the home support seemed to regard the whole ground as their property (it had been entirely unsegregated as recently as 1979). So there were Telford fans mingling in the main stand paddock and Wigan fans scattered across the Shevington End, and while in both an uneasy truce prevailed you had the impression a goal would change all that.

Both end terraces seemed superficially alike. The ground was bowl-shaped, a throwback to Victorian times when it had been built for the purposes of athletics and bicycle racing (for humans) and ‘trotting’ (for horses), and the low perimeter wall behind each goal was semi-circular. The Town End opposite appeared bigger but that was an illusion caused by its having more concrete and less grass than the Shevington. Our end had a much smaller terrace but a much larger grass bank, and also boasted a ramshackle roof to the rear. This structure – put up in the late Seventies to replace a much larger cover intended for seating, which however finished up being sold for scrap – was something of a Hobson’s choice for away fans. In bad weather at Wigan you could either be dry and muddy or wet but clean.

Wiganers who wanted shelter without the frisson of rubbing shoulders with the travelling support opted for the highly partisan Popular Side to our left. Any Telford fans in there kept themselves firmly to themselves. The Pop was a long covered terrace with a lean-to roof in two dog-legged sections, dating respectively from the 1920s (the part nearest us) and 1950s. After some fractious encounters in Wigan’s early Football League days this now boasted a nice white fence separating it from the Shevington, complete with the usual mob of growlers on the other side. The fence’s effectiveness was, however, undermined by the thigh-high barrier around the pitch – a flaw not lost on Millwall fans, whose recent antics were the subject of harsh official disapproval in today’s match programme.

To our right was the ground’s only seated stand, a great slab-sided thing perched on the half-way line. This presented a sooty brick facade to the car park and a high and steep upper tier to the pitch, and was fronted either side of the players’ tunnel by a standing paddock made of paving stones. The Phoenix Stand – so-called because it was built in the early Fifties to replace an earlier structure destroyed by fire – had been designed to run the length of the touchline, but due to lack of funds only the centre section was ever built. This explained its disproportionate height to width ratio, which permitted modest executive facilities in the space between the paddock and the seating rake. (Even as we froze on the Shevvy, Telford’s directors were enjoying what they later described as generous hospitality in this suite. Some lucky members of the official party were proudly presented with Wigan keyrings.)

The game

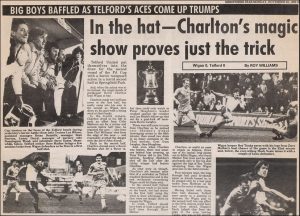

Looking back across nearly four decades and simplifying somewhat, this match was about one man – Telford’s goalkeeper Kevin Charlton. An agile player with a Second Division pedigree (he starred as a youngster in Hereford’s mid-Seventies team), Charlton came to Telford in 1981 as one of a number of players recruited by United manager Stan Storton from his former club Bangor City. He lived on Anglesey, which in 1980s Shropshire gave him a certain cachet, and was the archetypal mad custodian. His stature and appearance closely resembled that of Wolves’ equally eccentric no.1 John Burridge. On his day he was a genius. What I remember most about this afternoon are firstly the biting wind and secondly Charlton, cat-like, watching Wigan efforts rebound off his post and crossbar and clawing away one goal-bound attempt after another.

This being a Cup tie, of course, the story didn’t end there and the teams replayed at the Bucks Head the following Wednesday. The second match was disorganised chaos as a 5000-strong crowd tried to get into the creaking old ground. Quarter-mile long queues stretched as far as the Cock Hotel and in the absence of adequate segregation there was vicious fighting, a feature of big Cup-ties we would soon get used to. Wigan took the lead but goals from Alan Walker and Mark Neale – like Charlton, stars of the first game – won it for Telford. The Whites would go on to beat a further seven Football League teams over the next two years, but Lloyd wasn’t happy about being the first. He grimly marched his players straight onto their coach and away into the cold Shropshire night.

The JJB Stadium

For much of its life Springfield Park felt far from hemmed-in. There was a full-sized training pitch behind the Shevington End with room over for at least another two. To the south lay another area of open space which for many years held only scattered kennels and farm buildings, and beyond this stood the Woodhouse Lane Stadium. This staged dog racing (and briefly speedway) between 1928 and 1961. Latics were allowed to buy the football ground from the track’s owners in 1932 on condition they would never use it to race greyhounds. The area behind the Popular Side also remained undeveloped until St Andrew’s Drive was built in the 1950s.

In hindsight this last event spelled the end for football on the site, rather than (as it might have seemed) the requirements of the Taylor Report. Redevelopment was an inevitability at some stage but with better access Springfield Park might have had the best of both worlds. As it was, when sportswear millionaire and former Blackburn Rovers star Dave Whelan became chairman in 1995 the simplest option was to build a new ground. This he proceeded to do on a derelict canalside a mile or so to the south. Shortly afterwards Wigan Warriors became tenants of the Latics at the new JJB Stadium, having sold their much-loved Central Park to Tesco.

The relocation threw up some cultural challenges. Despite its shabbiness Springfield Park had been enormously important in the history of Wigan sport, and from the early days of trotting and running was regarded more as a public asset than private property. (Latics were in fact the sixth club and the second Football League side to play there, taking over from Wigan Borough, founder members of Division 3 (North) who folded in 1931.) To this day many supporters feel Whelan could and should have made more of an effort to stay at their spiritual home, and that the Council might have been more willing to help him.

Sharing with rugby was also controversial. Bad blood between followers of both codes goes back generations in the town. The poisonous 1980s relationship between the football and rugby clubs, abetted by local media and politicians, generated massive resentment among Latics fans. The football club’s recent dominance has had a similar effect on the oval-ball fraternity. An uneasy co-existence at the JJB (now DW) stadium hasn’t improved matters, and their tenant/landlord relationship causes further tensions. In 2008 Warriors fans were furious when the rugby team were forced to move a Super League play-off match to avoid clashing with a Latics game against Sunderland.

Last but not least is the stadium itself. The DW, not to put too fine a point on it, is dull. It also has twice as many seats as Latics need. Whelan’s project was predicated on Premier League football. When he delivered this between 2005 and 2013 crowds were respectable, with even the odd full house when the likes of Liverpool and Manchester United came to visit. But either side of that era four-figure gates have been the norm. No amount of excellent pies (which they surely are) can relieve the grimness of a sparsely-scattered crowd against Swindon or Shrewsbury in the damp gloom of a Wigan winter.

It’s on such days that the ghosts of Springfield Park call loudest. “I miss those old grounds”, someone remarked to me recently. “Going arse over tit on the grass bank at Wigan in the rain was a rite of passage.”

Teams: (from programme)

Wigan: Tunks, McMahon, Weston, Lowe, Cribley, Methven, Butler, Langley, Bradd, Houghton, Sheldon.

Telford: Charlton, Lewis, Turner, Mayman, Walker, Martin, Barnett, Neale, Mather, Hogan, Alcock. Sub: Gardner.

Attendance: 4805.

(I’m grateful to springfieldparkmemorial.weebly.com for some of the factual information in this article.)