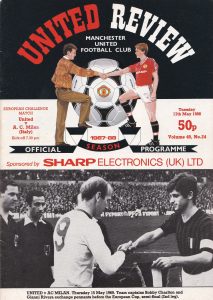

Manchester United 2 AC Milan 3

“European Challenge Match”

17 May 1988

The context

English clubs were banned from European competition following the 1985 Heysel tragedy. The only way they could play overseas teams was in friendlies. These were still permitted, in principle at least, but by and large there was little appetite for them and as a consequence the domestic game became ever more inward-looking. The European Cup, Cup-Winners’ Cup and UEFA Cup were no longer features of dark winter evenings, and instead we were treated to insipid surrogates like the Screen Sport Super Cup and the Full Members’ Cup.

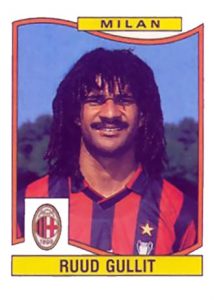

By 1988 there were serious concerns that, due to this exile, the game in England was falling behind its competitors. Particularly worrying was the indefinite nature of the ban (in the event it lasted until 1990). This was the backdrop to a very high-profile late season encounter hosted by a United team, in Alex Ferguson’s first full season, about to finish runners-up in the First Division. Their opponents, the new Serie A champions, had a star-studded squad that included Marco Van Basten and Ruud Gullit, pivots of a Netherlands team shortly to be crowned champions of Europe. The game was heralded as an important test of English teams’ quality (or otherwise, depending on which paper you read).

I’d been United-watching on and off for the previous three years. This was an disappointing yet at the same time eventful period that saw the departure of flash but inconsistent Ron Atkinson, the underwhelming arrival of Ferguson, the 30th anniversary of Munich and the ongoing irritation of Liverpool and Everton’s dominance. We’d started with the irrational excitement of 10 straight wins at the start of 1985-86 (which culminated in the Reds famously finishing third in a two-horse race), survived the stagnant season that followed and now we were at the end of another campaign characterised by grumpy underachievement and a steady decline in crowds once the team were out of the Cup.

This year the coup de grace had arrived in the 5th Round, courtesy of a home defeat by old foes Arsenal featuring a celebrated penalty miss by Brian McClair. United’s progress to that stage had masked a number of shortcomings. Despite being second in the table they were 9 points behind a rampant Liverpool and had never remotely been in the running. For this game they wore their white away strip, allowing us to see the Rossoneri in all their glory. The occasion felt almost dangerously exotic, the equivalent in Thatcher’s Britain of coming across a bar alla moda in Burnage.

The history

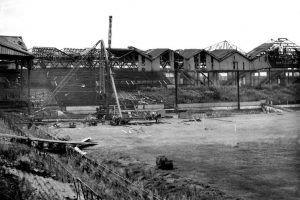

Like one or two other grounds, Old Trafford’s post-War development owed much to the Luftwaffe. It was severely damaged by bombing on 11 March 1941, as tons of high explosives intended for the nearby docks overshot their target and destroyed the main stand. Until then it was virtually identical to Maine Road, a substantial terraced bowl with a moody, strut-lined seated stand overhanging one touchline, but from that point onwards the two evolved in very different ways. For now, though, the damage was sufficient to force United into an eight-year exile at their neighbours’ home, during which time they attracted their record crowd in January 1948 when 83,260 watched them play Arsenal.

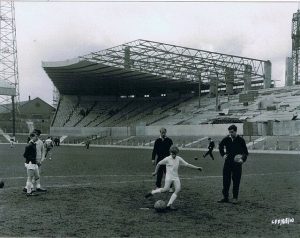

The modern history of Old Trafford is all about the cantilever. The Main Stand was roofed in 1951 and the Stretford End cover went up eight years later, meaning that all four sides now had some sort of shelter. But the ground suffered from an abundance of intrusive pillars, so ahead of the 1966 World Cup a magnificent new stand was built on the United Road side with no pillars at all, executive boxes at the rear and terracing in front. This was continued round onto the open Scoreboard End in 1973, and the addition of another cantilevered roof to the Main Stand in the mid-Seventies meant that only the Stretford End prevented Old Trafford from being a perfect bowl – a unity of design, capacity and atmosphere like no other ground at that time.

The journey

We usually caught the football special from Oxford Road station. The station was an easy walk from our house in Rusholme and had a handy pub next to it, the much-loved Salisbury. In an unashamed ploy to keep riff-raff off the service trains, the special ran non-stop to the ground’s own halt which was straight outside the turnstiles and only opened on a match day. This spared you the long road from Deansgate, often the scene of enthusiastic disagreements between the Red Army and visiting lunatics who fancied taking them on. And it led us naturally to gravitate to the Stretford End rather than the bustle of the forecourt or the simmering anarchy of United Road.

Unfortunately tonight, with this being a friendly, no-one had thought to arrange any specials and we found a scene at Oxford Road reminiscent of the Tokyo Underground. It was obvious everyone going to the match had thought they’d be the only ones there and left it till the last minute to set off. After a succession of Manchester’s less than spacious commuter services had left without us (and several thousand other people) on board, we finally managed to cram ourselves into a three-carriage train with about 500 others equally eager not to miss the rapidly approaching kick off.

The ground

If Maine Road was a sprawling, haphazard and dog-eared jungle, Old Trafford was a severely formal red-brick garden. Maine Road’s floodlights were tall and willowy, Old Trafford’s were solid, stocky and immovable. City had a sense of space badly utilised, United wasted none. By the time of this game the ground had achieved its final pre-Taylor condition. To the regret of many, roof-mounted lights had replaced the four 1950s-era pylons during the previous summer, but otherwise (with the exception of a corner join between the Main Stand and Scoreboard roofs added in 1985) the ground retained the shape it had since the cantilever was completed. The Stretford End in particular had changed little since the days of Law, Best and Charlton.

Part of the romance of Old Trafford lay in its nomaclenture. Despite now being effectively an oval it retained its four traditional elements – the Stretford End, Scoreboard End, Main Stand, and United Road – and both seating and standing on all four sides. Within this basic plan various parts were labelled mysteriously as “groundside” (the low-down bits) and “paddock” (the corner part of the Stretford where it met the Main Stand). The shades were uniform red and grey – red seats, red barriers, red radial and perimeter fencing, concrete walls, chunky concrete crush barriers. For all this colour the ground was somewhat drab and (for away fans) unwelcoming. It blended in with rather than dominated the harshly industrial dockland buildings that still enclosed United Road and the back of the Stretford.

Two things always surprised first time visitors to the Stretty. One was that the Paddock’s terraces were largely made of wood. Any accoustic benefits this might have bestowed were negated by its popularity with the end’s quieter citizens, a stigma not helped by the corner location and some awkward struts holding up a clumsy roof. The second was that, uniquely among the great terraced ends, it had a seated section at the very back. This was an antiquated area with wooden benches and flooring, accessed by separate stairways to the Stretty proper and completely separate from it. The fans who sat there were generally a restrained bunch who nonetheless had probably the most interesting view in English football.

In the early and mid-Seventies, when United fans in Bay City Rollers gear ran amok through the market towns of England and its allure drew in disaffected youth from all over the country, the Stretford End had been genuinely a sight to behold – a roaring, swaying, fearsome mass of aggressive humanity. These days Old Trafford’s more lawless fringe frequented K Stand and United Road, but the Stretty was still a lively place where a post-goal “mental” could move you down and across the terrace and separate you from the people you went with. Like most ends at that time, its younger element was a loose affiliation of neighbourhood Manchester gangs who generally put their differences aside on a match day. But that wasn’t to say they couldn’t get on each others’ nerves, and during a boring game or one with a poor away following it was a wise precaution to be aware of who you were standing with.

The game

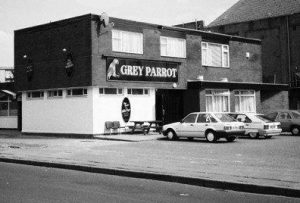

Now the picture above isn’t us. Although we weren’t exactly fashion icons we’d at least discarded flares. But it does show what queueing to get into the Stretty used to be like, back in the days when Old Trafford was still foreboding and post-industrial. This end was hemmed in by walls and United Road was still a road as opposed to an idea, meaning that (for reasons that were never made clear) the police were very keen to keep fans off it. The gates were seldom locked at United in the Eighties and there was little enough incentive to arrive early. So as kick-off drew near the line grew as the pubs emptied, until it snaked down towards the main stand then doubled and ran back up the opposite side of the street. Horses kept you off the roadway, and not nice horses and nice policewomen like this. Dirty big horses and dirty big coppers, with dirty big sticks they’d whack you with if you dared step off the pavement.

As a nod to the past, on a match day I would sometimes gravitate to my Dad’s old boozer, the Throstle’s Nest on Seymour Grove, a brisk twenty minutes away from Old Trafford. I grew up in this part of Manchester and United had club houses near us, on Rye Bank Road and Erlington Avenue, so our neighbours at different times (not that we knew them) included the Ures and the Crerands. The Quadrant, behind the cricket ground, was also a memory from my childhood. The route to the ground from here took you past the crumbling remains of White City, Manchester’s erstwhile greyhound, speedway, athletics and stock car stadium. This had fallen on hard times since its post-War heyday and was closed in 1982.

Sadly there was no time for boozing on that balmy evening. The desperate pack of delayed fans had cantered out of Old Trafford station, past the cricket ground, past White City, down Warwick Road (stopping the traffic en route), past Macari’s chippy, across the forecourt, under the tunnel and was now trying to get in. None of your delayed kick offs here. We lost one of our party (it later transpired he narrowly escaped arrest for complaining when a police horse broke wind in his face). How much of the match did we miss? I can’t remember. But we saw all the goals.

The game was something of a non-event. Milan ran up an embarrassingly easy 3-0 lead on a pig of a pitch, abetted by a comedy Van Basten dive, before losing interest and letting United scuff a couple. Gullit looked bored by the whole thing and ignored the Stretty’s request to give them a wave, whereupon they gave him some gestures of their own. The crowd was 37,000-plus, more than watched a lot of League games that season. Many fans didn’t make it into the ground until half time, and many left before the end (maybe to make sure of a train). Those who bewailed the decline of the English game looked smug, Saint and Greavesie polished off a few dreadlock puns and we went to the pub and looked forward to next season’s FA Cup.

Squads

Manchester United: Albiston, Anderson, Blackmore, Bruce, Davenport, Duxbury, Gibson, McClair, McGrath, Martin, Moses, Olsen, Robson, Strachan, Turner, Walsh.

Milan: Ancelotti, Baresi, Van Basten, Bortolazzi, Colombo, Donadoni, Evani, F Galli, G Galli, Gullit, Maldini, Massaro, Mussi, Nuciari, Tassotti, Virdis.