Despite being the first of a trilogy this book stands pretty well on its own feet – just as well, given that (in typically disorganised fashion) I read its companion volumes, Bournemouth 90 and LS92, first.

We have a national fascination with 1960s subculture. At first glance Morris fails to break any new ground: protection rackets, controlling doors and selling pills feel like familiar territory, Father Ernest’s interest in dentistry is inspired by “Mad” Frankie Fraser, Quadrophenia explored the whole scooter/café/annoying Mr Big thing thoroughly enough. If you need amphetamine-crazed Americans try Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. So what makes LS65 different?

First – and most obviously – the action takes place in Leeds. This is fertile territory for any author, because searching “Leeds gangster book” gets you multiple Service Crew hits and not much else. Taking full advantage of this gap in the market, Morris’ typically careful research has produced a unique historical account of his home city’s shady underworld. He can’t be blamed if much of it wasn’t very nice at all; our parents’ generation could be right vicious bastards when the fancy took them.

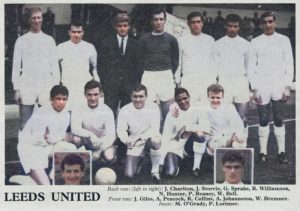

Secondly, football. As usual Leeds United provide a rich contextual backcloth that now and again features actual events. Their game against West Ham on 3 April 1965 is one such. You can practically smell and taste Morris’ description of 1960s crowds – queuing from midday, Westlers burgers, fans straining to hear team announcements on crackly speakers. Leeds won 2-1 that day, making crucial ground on leaders Chelsea; Alan Peacock and Billy Bremner got the goals in front of 42,000.

1964-65 had become quite the rite of passage. Don Revie’s team – only just promoted as Second Division champions – would be League and FA Cup runners-up, demonstrating an unfortunate tendency to fall at the final hurdle that eventually came to typify Revie’s brilliantly flawed time in charge. Off the pitch, Elland Road’s best-ever average crowd of 39,000 was 27,000 more than had attended just three years previously. “Success is the offspring of ideas and bravery”, as Alan Connolly remarks.

The psychotic Glaswegian hits beckoning opportunity at its tidal flood. Two things could be sold for top prices in 1960s Leeds – drugs, and Leeds United tickets. Connolly wastes no time trying to get rich on the proceeds of both, hampered equally by evil gangland bosses far cleverer than he imagines them to be and gormless accomplices who don’t share his enthusiasm for gratuitous violence. A regular “Tick tock” refrain soundtracks the timebomb of this rawly ambitious yet fatally disturbed mind.

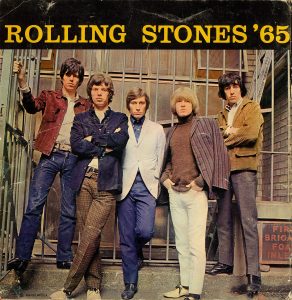

Amphetamines and the Mod movement often went hand in hand. So-called “modernists” had been a youth phenomenon for some time, although their interests were now trending towards Italian scooters and Motown/R&B rather than the early focus on jazz and sharp, tailored clothes. These tensions run though LS65, where Connolly and his group hold strong opinions on each. “The Stones aren’t Mods”, declares Norman heatedly. “They’re dressed-up art students who’ve stolen and massacred classics by proper artists like Muddy Waters, Chuck Berry and Ben E. King.”

Leeds Mod culture centred around Boar Lane. The Del Rio, Concadora and El Toro cafes became well-known meeting points, as did the Carousel on Upper Briggate. The Blue Gardenia (Bee Gee) and Three Coins, meanwhile, regularly hosted live music. These venues all feature in LS65. Mod/rocker rivalries were also still very much alive. Greasers dominated Elland Road’s fighting hardcore, which meant that domestic conflicts sometimes overflowed onto the terraces.

Match tickets were harder to find than pills and bands. Modern readers might not understand just how sought-after tokens used to be; a match programme confirmed attendance, therefore loyalty, which in turn gave priority for big games. Good luck today finding Leeds programmes from the Sixties that haven’t been mutilated by token removal. Connolly’s attempt to bypass orthodox methods – such as romantic influence in the ticket office, and tapping up young players (Gray, Lorimer and Greenhoff make brief cameo appearances) – proves pivotal.

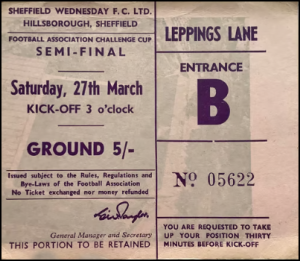

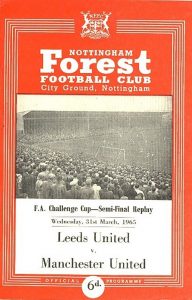

If the botched token robbery divides loyalties within Connolly’s gang then so too does football. We’ve all made trade-offs between working, domestic responsibilities and seeing the match; stakes here are considerably higher, not least because a Cup Final place beckons. “I’m sorry boys, but business is business”, Connolly says as they exit Hillsborough after the 0-0 semi final draw with Manchester United. “You can fuck off, Alan”, mutters Wesley. “I’m off to Nottingham whether you like it or not.”

I mentioned the book’s successor volumes. Morris introduces themes here that permeate all three. His characters almost always fall into juxtaposed types – disturbed individuals like Connolly that nevertheless exert vital life force, and others whose own reasonable passivity proves their major flaw. Social upheaval and gritty urban surroundings act on them all to ensure no-one ultimately remains untainted.

The Stones may or may not have been Mods, but they could have been describing Alan Connolly in 19th Nervous Breakdown:

You were still in school when you had that fool who really messed your mind/And after that you turned your back on treating people kind.

Tick tock. Tick tock.