Walsall 1 Rotherham United 1

Football League Division 3

Tuesday 1 May 1990

The context

Living in Brierley Hill and watching most of our football at The Hawthorns, we’d gone the way of so many other local fans down the years and taken to visiting Walsall when Albion were away from home. In the late 80s this was an unfortunate habit to develop. Promoted against the odds to the second tier in 1988, the Saddlers barely won a game for the next two seasons. But provided you could live with a team in terminal decline, Fellows Park was a pleasant enough place (at least on days when the fans weren’t trying to lynch John Barnwell). Its extensive terraces were almost totally covered, crowds were modest so there was room for everyone, and the bus from Dudley went right past the main entrance.

As someone not yet in the 92 Club despite having been to well over a hundred League grounds, it’s hard not to yearn for the 33 years from 1955 when not a single one was built – especially when so many these days look much the same. In 1988 the club breaking the mould was Scunthorpe, proudly unveiling the monumentally dull Glanford Park as the first new venue since the release of Rock Around The Clock. By contrast the next one, Walsall’s Bescot Stadium, took only two years to come along. And it was pretty much identical in size, shape and dullness.

The match

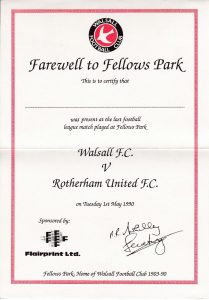

As the dawning of a new era, the long-awaited farewell to Fellows Park felt rather lacking. The game against a Rotherham side safely in mid-table and not really that bothered, who brought a travelling support of 15, was one of those languid rearranged matches that used to get tagged onto the end of the season after the rest had finished. Walsall, meanwhile, had done their best to spoil the party by having another shocking campaign and getting themselves relegated. The 5,697 who showed up saw Andy Dornan open the scoring only for Rotherham, in fetching pale lemon and sky blue, to equalise with the last-ever League goal at the old place. My main recollections – apart from the Millers’ shirts – are that it was a beautiful spring evening, the pies ran out, and the crowd refused to sing You’ll Never Walk Alone.

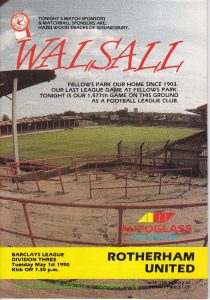

That last one has stayed with me as a warning of the risks of trying to choreograph football fans. Walsall, bless them, tried to make it an occasion with the limited means at their disposal. There was a special programme (“sponsored by Hazelwood Snacks of Wednesbury”) in which, for £1, you could have your name printed (I did). There was the Eureka Jazz Band. There were cheerleaders (the Summer Gold Dance Group). There were 1000 Balloons (Released From The Pitch). And then the crowd were expected to sing. By that stage, though, most of them were too busy booing the stewards and police who kept them off the pitch when all they wanted to do was run about a bit and dig up the centre spot.

Because this game marked the first of what soon became a tidal wave of ground moves, few of us completely realised how wide its implications were. Many of the things we took for granted were on borrowed time. Pay on the gate and inadequate pie planning were fast being consigned to history, and with them a simplicity we would eventually come to miss very much.

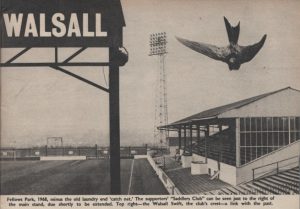

Fellows Park

No-one seems to have taken much notice of Walsall until 1933, when the Third Division (South) club hosted, and improbably beat, Herbert Chapman’s all-conquering Arsenal side in the FA Cup. In the run up to this seismic event, various improvements were made (presumably very hastily) to a 34-year old ground that a short time before consisted largely of cinder banking. The Main Stand had opened only a short time previously, and now a cover was built over the terracing opposite. Both these structures survived until the end, the long and prominent Popular Side roof serving for many years as a massive billboard for various niche Midlands products.

By the time we got there the original terraces had been concreted, but the corrugated-iron cover on the Popular Side was still very much in its 1930s state. Originally protecting only the back of the terrace, at some point the shelter available had been increased by the simple expedient of building another roof in front of, and not remotely connected to, the old one. This looked pretty ancient too, and together they made viewing from the rear of the banking a uniquely challenging experience, as well as a wet one when the not infrequent rain of a Midlands winter poured through the crumbling structures and the gap between them.

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

1 mis-sized (Alex Mowbray) 2 popular side 3 Hillary Street End (Alex Mowbray) 4 Railway End 5 seats

An extension was added to the eastern part of the Main Stand in 1965. At the same time the club built the first stage of a roof at the Hillary Street End, which eventually acquired a confusing array of mis-sized additions to join it with the Popular Side cover. But the biggest event of the year took place with the demolition of Orgill’s Laundry, which for 70 years presented a blank brick wall to that end of the ground. For the first time Walsall could allow spectators behind both goals, and a new (if narrow) terrace appeared at the now-renamed Railway End. In later years this would become the area for visiting supporters.

By 1989 Fellows Park was a bit of a rathole. Capacity was seriously down from the frankly ridiculous 25,500 that somehow squeezed in for a Sixties game against Newcastle, but even so the perimeter wall at the Railway End collapsed in 1983 (fortunately without serious injury to anyone) during an improbable League Cup semi final with Liverpool. In its last days a falling out between Bristol City fans and the WMP’s finest led to that part of the ground resembling nothing more than a zoo. Even by 1980s standards the toilets were the stuff of legend, and the Hillary Street roof flapped in high winds and showered fans with rusty water during matches on wet days.

Despite its shortcomings, however, for Walsall’s 6000 or so regular fans Fellows Park was home. In those simpler times their support base combined local diehards and to a lesser extent followers of the “bigger” local sides, many of whom regarded Walsall as a second team. They had endured a torrid couple of years. By the time the last game at Fellows Park came around it was certain that the Saddlers would start life at Bescot in Division 4.

Bescot Stadium

Scunthorpe left the Old Show Ground because Safeway made them an offer too good to refuse. Fellows Park also ended up as a supermarket – Morrisons – but the precise circumstances are rather less clear. The Saddlers had been owned through the 80s firstly by scrap dealer Ken Wheldon, who made himself enormously unpopular by trying to sell the ground and move Walsall in with Birmingham City, and then by the flash but cash-strapped Terry Ramsden. Now the traditional “consortium of businessmen” was shifting them to a brownfield site (quite literally, as it had previously been a sewage works) underneath the M6. And by a stroke of good fortune one of them owned a building company.

The new ground was not a high-end project. The directors seem to have happily cut overheads by simply pointing at the blueprints for Glanford Park and saying “One like that please, but with more pillars.” Leaving aside the finance of the deal, which unravelled remarkably quickly over the seasons that followed, this was an audaciously self-centred approach. From the fans’ perspective, Bescot’s only plus point was that it was less likely to fall on their heads and the toilets had a roof. Set against that it was dearer to get into, the seat/terrace ratio was in inverse proportion to that at Fellows Park, and the builders had somehow managed to put even more intrusive metalwork between the crowd and the pitch.

When we went along for the first game of 1990-91 we were almost painfully disappointed. The grandly-titled “stadium” resembled a factory unit with a football pitch in the centre. It was uniform on four sides, a shallow bowl with two seated stands and two terraced ends. Neither terrace had even the capacity of the shabby old Railway End, and the home one overflowed five minutes into the game and fans had to be relocated for free into empty seating blocks. Ironically this improved the atmosphere somewhat. But it was too little too late. Like Peter McGough, we’d seen the future – and we weren’t going.

(I’m grateful to Alex Mowbray for permission to use some of the pictures in this article. They originally appeared on www.fellowspark.wordpress.com)