Bedsheets and bootboys

Exeter fans enjoyed the late 1970s. Bobby Saxton’s team were promoted in 1977, ending ten straight years of basement football; successor Brian Godfrey might well have taken them up again, had not a remarkable run to the FA Cup sixth round stretched his limited squad too thinly. But even as City schoolyards echoed with talk of Johnny Hore, Tony Kellow and Alan Beer, “aggro” also aroused our youthful interest. Grounds back then could be excitingly dangerous places.

This clip is via Britain On Film. It illustrates both St James Park’s particular ambience, and also just how brutal some fans could be. Those railway sleepers in the Cowshed were much beloved of City’s more territorial followers. Held together only by discarded ring-pulls and the dust of decades, they would eventually be replaced with concrete terracing post-Bradford. The Cowshed itself dated from 1926; building work had been suspended during the General Strike.

The (incorrectly-titled) film shows City’s League Cup tie against much-disliked rivals Plymouth on 13 August 1977. Both clubs abandoned tradition that season and played in white; Argyle are wearing their yellow change strip, while the unfortunate fan getting battered – whose avant-garde dalliance with replica kit seems to have attracted unwelcome attention – has chosen a more familiar Exeter shirt. Alan Rogers’ ankle tap on the pitch invader remains my own favourite moment.

League Cup ties used to take place before the season proper. Regionalised draws meant plenty of local derbies; Exeter had also played Argyle in 1976-77, winning both legs 1-0. Highlights from the game at Home Park can be seen here . This season’s games finished 2-2 and 0-0, so – typifying more carefree days – everyone went back to Plymouth a week later, where Beer scored the decisive goal.

Both films show typically haphazard policing. Designated visitors’ areas back then were often more anecdotal than real, and no-one paid them much respect anyway. When away from home you could either try to avoid attention by keeping quiet, or band together – whether for safety or rather more aggressive reasons – with others. In either case simply attending football often became an edgy, rough-and-tumble business.

Argyle’s “mental” turnout at Exeter on that summer Saturday was much bigger than most lower-league travelling supports. But potential for fighting of the nastier sort – at that time far more normalised in society – always existed. And although a few violent criminals undoubtedly saw opportunity for twisted amusement at football matches, many more of us simply got caught up in the moment.

Wolves at the door

Freedom of movement around many grounds allowed livelier away fans to try and infiltrate areas favoured by hardcore locals. For this reason another chant often heard in Exeter playgrounds was “You’ll never take the Cowshed”. Those wooden sleepers – despite any superficial charm the Shed’s sloping corrugated iron roof might have had – were no pushover, even for Union Street-hardened “bays” brought up on Plymouth’s tough 1960s council estates.

The Cowshed could have been specifically designed for deterring invaders. Its rear overlooked a school playground, so you had to enter from either end. Lack of gangways made getting in difficult and escaping even harder, while the adjacent away end at St James’ Road narrowed conveniently above one corner flag. Attacking the front – six feet above pitch level and fronted by grass banking – would have been utter foolishness.

City’s win against Plymouth set up a home tie with Aston Villa. Almost 14,000 fans saw them battle bravely but lose 3-1; Andy Gray’s two goals for Villa are shown here . Other early performances, too, were more consistent than results suggested. Saxton’s promotion team remained largely unchanged, save for the return of injured first-choice goalkeeper Richard Key – ably deputised by 19 year-old student John Baugh since March – and Beer’s enforced retirement.

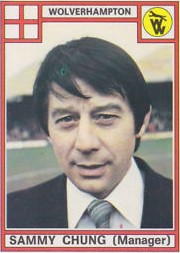

The powerful striker was about to join Leicester City and had just been selected for Wales. But now incurable knee damage left skilful youngster Harry Holman partnering Kellow’s predatory talents instead. Nineteen year-old Holman was a former Chelsea apprentice, whose father – also Harry – represented City immediately after World War Two. One of his best performances that season came when Exeter played Sammy Chung’s First Division Wolves side in the FA Cup.

Wolves were also newly promoted. This game therefore caught both clubs at a defining moment. Its events would have been memorable enough anyway.

The basic facts are these:

- Willie Carr’s first half free kick put Wolves ahead; Exeter came back to lead with goals from Lee Roberts and Holman, Maurice Daly equalised late on with a spectacular long-range shot;

- 14,377 attended. Most estimates put Wolves’ travelling support between 3,000 and 5,000;

- Wolves won the replay 3-1.

Some enduring legends also persist. I have no reason to doubt any of them:

- Vandals from both sides mis-spelled “Wolves” as “Wovles” in separate pieces of graffiti near the ground;

- Some Wolves fans wore pillowcases on their heads;

- Exeter’s worst ever football hooliganism took place .

And the band played on

Some Exeter fans’ recollections from exeweb.com . References to the 1970s layout of St James Park may be better understood by referring to this article .

“I remember old fellas around me In the Big Bank shaking their fists at Wolves fans who had run the length of the pitch to jump into our end. They jumped in anyway.”

“I was in on the Big Bank with Wolves fans in their white masks right behind me. They had my scarf away before kick off and I had to endure aggro throughout the game. Much as it was sickening to concede a late equaliser, it may have been for the best; not sure what would have happened if they’d lost.”

“I was 12. As I walked to the ground I was threatened by a Wolves hoolie who called me a ‘”fucking little Exeter wanker’.”

“There was a local business at the time called Renwicks Travel whose mascot was a beaver. This was going around the ground throwing handfuls of sweets. When he threw some at the Wolves fans he got them all back with interest.”

“I vaguely remember there was a band. A load of Wolves fans invaded the pitch and ran through them while they just carried on playing.”

“It was all a bit surreal with the Wolves lot charging from the Big Bank and climbing into the Cowshed via the grass bank. I still remember it vividly.”

“Wolves didn’t take the Cowshed. They were successfully repelled by all and sundry. They did sneak in during the second half via an open gate from the St James Road end, but were soon sent packing by some of Beacon Heath & Burnt House Lane’s finest.”

“A day I’ll never forget. I was in the Shed (aged 13) and was very, very scared at the final whistle. Harry Holman was brilliant and we were so unlucky as it looked like we would hold on for a famous victory. I think they equalised with about 5 minutes to go. Scenes of carnage during and after the game. Fence collapsing in the away end, crossbar broken.”

“Fences going over at the away end, late equaliser for Wolves. Looking back as I headed down the Jungle Path just in time to see the crossbar snap.”

“The coaches that brought Wolves fans were parked on Union Road and after the game they went up Victoria Street putting out windows. They were, however, locked out of the Vic where I was cowering.”

“The Ku Klux Klan outfits are my most vivid memory, and the fighting on Sidwell Street roundabout after the match. I also remember sitting in the Black Horse pre-match and counting Wolves coaches going past. When I got to 30 I removed my scarf and stuffed it down my jacket.”

“I was there aged 16 in the Big Bank. It’s a shame that memories of the trouble overshadow the match, which we were on the day easily good enough to win. It’s the only City match ever that I have left before the final whistle, because I knew what was going to happen next. Thank God those days are gone.”

The sound of breaking glass

These Wolves fans’ memories are from molineuxmix.co.uk .

“Went down with some pals on a Don Everall coach. One of my mates ran on the pitch and was rugby tackled by a WPC.”

“My mate Vincent got off the first Wolves coach to arrive and was met by the Lord Mayor – in full civic regalia – who welcomed him to Exeter. Vincent looked at the outstretched hand of friendship and smartly popped his nose.”

The firemen’s strike was on and the Staffordshire Regiment were manning fire engines. One parked just outside and a fireman with a Wolves scarf on was sat on top watching over the wall.”

“Wolves fans packing both ends – a few dressed as the Ku Klux Klan. A school and basketball court directly behind the end I stood on. Advertising hoardings broken down when Willie Carr scored, due to the crush. Corner snack bar roof ripped off at half-time, free crisps for the fans. Maurice Daly’s thunderbolt equaliser causing mass pitch invasion. Gary Pearce carried on fans shoulders through rail tunnel near the ground afterwards.”

“Police just pushed us in the ground without using the turnstiles. Sure it should have been their end as a few Exeter fans were tying to be anonymous near us. We stood in front of a clubhouse, but had to move when it became the target for some Wolves fans missiles. I remember leaving the ground to the strains of ‘were the best behaved supporters in the land’, accompanied by the sound of breaking glass, sirens and God knows what else.”

They were totally unprepared for our support. We were crammed in a tiny end behind one goal with a three foot high brick wall at the front. An Exeter flag was flying next to the portable canteen in our end – Wolves fans took it down and hoisted a gold and black scarf in its place. Our end was crammed, an hour before kickoff the brick wall collapsed and hundreds of us fell forward onto the pitch. I remember ending up standing near the brass band playing on like nothing had happened.”

“Everything was friendly until the fighting and pitch invasions started. Then fences and hoardings were used as weapons – Exeter fans didn’t know where to run, it was complete chaos. A couple had some old pillow cases. They had cut some holes out so they could see and breathe. Everyone was laughing at them and it was all tongue in cheek.”

“The game will always be remembered for the hooded fans. The national press had a field day, saying that Wolverhampton was the Ku Klux Klan’s new home and rubbish like that.”

“The Ku Klux Klan came to Wolverhampton afterwards for some meetings but they left saying there wasn’t sufficient support.”

“A picture in one of the tabloid papers entitled ‘The Ku Klux Fans’ got a lot of attention. They later reported racist attacks against Asians in Wolverhampton by people dressed in hoods.”

“I remember being on the pitch at the end and running to that side stand with the grass bank. It was surprisingly steep. That was the darkest stand I have ever seen.”

“I was walking back to the coaches afterwards along streets of terraced houses and suddenly heard a huge crash as a brick went through someone’s front window.”

“What sticks in my memory is seeing an old lady in an apron stood on the doorstep of her house, looking at the broken glass of her window. I still feel ashamed of some fellow supporters that day.”

“Exeter was scary. Our fans were animals.”