The club

Victorian Glossop was a mill town – whether calico, paper, or cotton, chances were if you lived there you worked in one. It was free of many of the industrial tensions suffered by neighbouring towns, principally because the local employers were reasonably public-spirited and altruistic. “The mill owners were the local aldermen, the church elders and led the sports teams”, writes one commentator. “The relationship between the owners and men was one of paternal benevolence.”

That did not mean, however, that they all got on – they were rival businessmen, after all. The Partingtons competed with the Woods and the Rhodes’ competed with the Sidebottoms, principally in terms of who could fund the best public buildings or make the biggest contribution to local life. “The Woods built the public baths and laid out the park….Partington built the library and the cricket pavilion….so Wood sponsored the football club”, writes the same author.

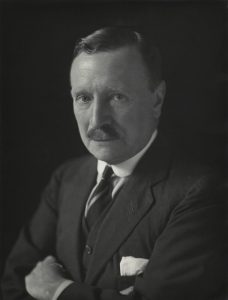

This was the environment that created Glossop North End, via its principal benefactor Samuel Wood – mill-owner, County cricketer (he captained Derbyshire for three seasons) and MP. Wood was the Eton-educated son of a wealthy local industrialist, and he invested a reputed £30,000 of his personal fortune in the football team and in persuading talented players to join it. He changed his surname to the more distinguished-sounding Hill-Wood in 1912, soon after becoming Conservative member for High Peak.

Glossop even now is small and badly served by modern roads, but at the turn of the twentieth century it would have felt a million miles from football’s top table. It is in this world that you need to imagine both the team and its early context. Remember this and it feels even more creditable that the club managed to attract a clutch of big-name (if slightly past their best) players in its Football League days.

One such journeyman was Bob Jack. 32 years old when he joined Glossop in 1902, Scotsman Jack had top-scored at Bolton and Preston. He spent a single season at North Road, subsequently moving a very long way from his Alloa roots to coach first Plymouth and then Southend, before returning to manage Plymouth for an incredible 28 years.

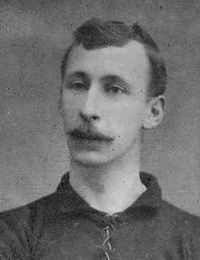

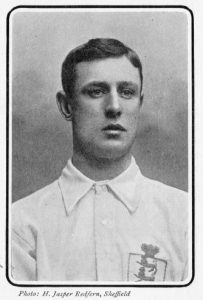

For sheer impact on the game, however, Fred Spiksley remains the most significant player to have worn Glossop colours (now, blue: back then, I have no idea. The pictures suggest predominantly white, with a variety of surprisingly modern flashes and pinstripes).

Spiksley was, even by the Empire-building standards of his day, an interesting character. A recent book, Flying Over An Olive Grove by Clive Nicholson, Ralph Nicholson and Mark Metcalf, looks in detail at his life: while Glossop was little more than a staging post on his journey, that was also true of Leeds City, Watford and England (for whom he won 7 caps). Best remembered as a Sheffield Wednesday player, Spiksley actually ended up there by accident. En route from his home in Gainsborough to join Accrington, he stopped off in Sheffield, where he got talking to two Wednesday directors who persuaded him to sign for them instead.

A womaniser and a compulsive gambler (he died aged 78 in a heatwave at Goodwood Racecourse in the act of placing a bet), Spiksley was an expert dribbler and an accomplished goalscorer, with modern theories on physiotherapy and fitness. When his career was finished early by injury he joined Fred Karno’s Circus (where he worked with Stan Laurel and Charlie Chaplin), before becoming a football coach in Nuremburg. Interned at the start of World War One, he was obliged to negotiate his release from Germany, ironically by feigning injury.

Post-war, and with the exception of a stint at Fulham which did not end well, Spiksley found little appetite in England for his controversial coaching ideas (among other things he disapproved of heading the ball and kicking with the instep). Undismayed, he took his talents abroad and trained footballers in America, Mexico, Peru, Spain, France, Germany, Switzerland and Sweden. He won titles with Nurnburg and AIK Stockholm and managed the Swedish national side. Best of all, he was known in Germany as “Fred Fried Egg.”

One of Spiksley’s ventures was, in the 1920s, a series of Pathe coaching films (pre-dating YouTube by some 80 years). Here he is at Fulham, extolling among other things the virtues of the backheel.

The Finer Points Of Football (1929-1931)

The Finer Points of Football. Probably filmed at Fulham football ground (Craven Cottage), London. M/S of football coach Mr F Spiksley (sp?) on the pitch, standing between two players from Fulham called Barratt and Oliver. He says he is going to show us some finer aspects of the game.

[for much of this Spiksley content I am indebted to Simon Burnton’s Guardian piece of 28 July 2017.]

North Road

Like many clubs, Glossop played at a number of venues in the their early years, before putting down roots at North Road cricket ground in 1898. Following Wood’s determined bankrolling they had just been promoted to the newly-expanded Second Division of the Football League, after a number of seasons playing professionally in the Combination and Midland Leagues.

The site’s limited capacity would be tested until 1914, as Glossop became the smallest place ever to sustain a team at League level (a record only recently broken by Nailsworth, home of Forest Green Rovers). After finishing runners-up to Manchester City in their first season they competed in the top flight until 1900, hosting and beating teams such as Blackburn, Burnley and Aston Villa.

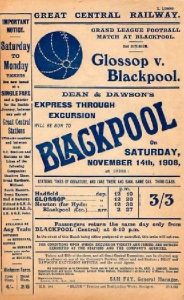

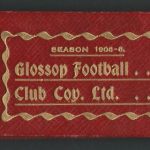

- front cover

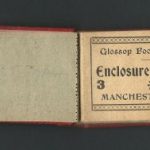

- under cover

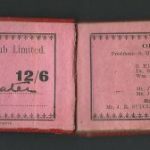

- 12/6

- lady’s tickets

The ticket book shown here is from the 1905-06 season, by which time Glossop (they dropped the North End in 1899, apparently to avoid being confused with Preston – which in new money would be like confusing Manchester United with Maidstone United) were back in Division Two and struggling somewhat. The game against United attracted an estimated crowd of 10,000, which must have caused chaos in the narrow streets around North Road, and horror among the genteel residents of the adjacent villas (the record attendance, 10,736, rolled up for a Cup-tie with Preston in 1914).

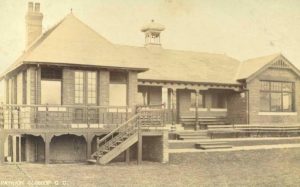

Glossop’s home, while essentially functional, had a couple of interesting architectural features. One was the ornate pavilion, shared with cricket and seemingly the only building of which photographs survive. The other was a “temporary wooden stand”, which apparently stood behind the westerly goal – ie the furthest from North Road – and was dismantled at the end of each football season and rebuilt in time for the next one.

North Road today

Not much remains of the football ground at North Road, although as there wasn’t a lot to see even in its heyday that isn’t really surprising.

It’s easiest to visualise where the ground stood if you imagine one touchline starting more or less at the point where North Road meets the railway bridge. There was banking here that continued between the pitch and the railway. The majority of the banking was around the corner section, where Ladybower Court now faces the road (the other wing of Ladybower Court is across the south-eastern quadrant of the pitch). There was a turnstile block across the line of the present driveway, and another, smaller gate towards the bridge.

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

1. approach under railway 2. site of banking (under flats) 3. corner of banking was here 4. site of turnstiles 5. ground site on right 6. approximate view from old pavilion 7. remains of banking 8. Surrey Street

The location of the modern cricket pavilion more or less follows that of the original structure, although the older building was aligned with the northerly touchline (again, think parallel to the railway). A section of banking remains alongside the flats, and this too is a reasonable indicator of scale and location.

Clearly this was not a big or particularly convenient venue. For much of its life it slumbered quietly, hosting local football in front of small crowds who had no need of larger or grander facilities. But in its dual cricket-football purpose it was typical of many small town sports grounds, of a kind that have now largely vanished. And for a single memorable year it hosted the best teams and players in the land.

Surrey Street

From North Road it is a short walk to Surrey Street, since 1955 home of the present-day Glossop North End (the club reverted to its original name in 1992, possibly to irritate Preston fans who sing about their team being ‘the one and only’). Surrey Street is itself an interesting place to watch football, not least because of the views from it and beyond it of the hills towards Buxton. For many years it was dwarfed at its eastern end, first by an iron foundry and later by the Ferros Alloy works, which boasted the tallest chimney in Glossop. These days the landscape has been softened by the construction of new houses behind that goal, although getting wayward footballs back has become much more difficult.

A high point for the modern club came in 2009, when they reached the FA Vase final and played Whitley Bay at Wembley (sadly losing, as was the case again in 2015 against North Shields). 2,374 packed into Surrey Street for the semi-final against Chalfont St Peter. They saw a penalty shootout win following a last-minute aggregate equaliser, amid scenes of excitement probably on a par with that far-off United game, and – thanks to ties of family and history – inextricably connected to it.

When he learned of Glossop’s success, Arsenal chairman Peter Hill Wood – grandson of Samuel – allowed them to use his first team’s training facilities at London Colney before the Final. And while that was a generous gesture, it drew unfavourable comment on the events of 1919, when football resumed after the War and the game’s administrators began studying the final Second Division table. Glossop, who had finished bottom, were not invited to re-apply. Arsenal were inexplicably and mysteriously promoted to the top flight instead of Wolves and Barnsley, who finished above them. And Samuel Hill-Wood sold his mill, moved to London, took his money with him and became chairman of the Gunners.

As Rudge put it in The History Boys, “history is just one f***king thing after another.”