Derby County 0 Swansea City 0

Championship

Saturday 10 August 2019

The context

You’ll never see the end of the road while travelling with me. John, Kieran and I were already running late en route to Mansfield v Morecambe; heavy traffic near Uttoxeter made us fretful about missing kick-off, so we settled instead for Phillip Cocu’s first home game as Derby manager.

John and Kieran never experienced the Baseball Ground’s unique charms. All three of us are, however, Pride Park veterans (John actually went – supporting Villa – during its opening season). Collective memory of routes and parking places got us there just in time to snaffle up some of the last remaining tickets; that small detail resolved, we headed pubwards while eagerly anticipating a thrilling afternoon of totaalvoetbal.

The history

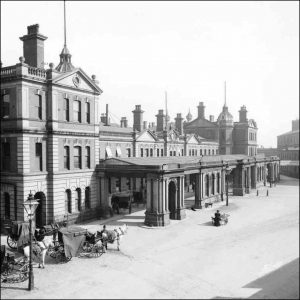

This was the western terminus of George Stephenson’s North Midland Railway. Trains from Leeds connected here with services to St Pancras and Birmingham. Their various operating companies shared one ornate station building – designed by celebrated architect Francis Thompson – that became known as the Tri Junct. All these concerns merged in 1844, at which time the combined Midland Railway opened its main engineering facility nearby.

By 1900 more than 8,000 local men worked on the railway. Locomotives and rolling stock were built and repaired, while a busy maintenance shed stood among extensive goods yards. Sidings sprawled for miles. Derby Works would ultimately produce almost 3,000 steam engines and more than 1000 diesels, with modern passenger trains still constructed at the Carriage Works site to this day.

Derby County had been League and FA Cup runners-up on four occasions during the 1890s. Centre-forward Steve Bloomer – a former blacksmith discovered while working at Ley’s foundry in Osmaston – would became one of their greatest ever players. England international Bloomer scored nearly 350 First Division goals; he then coached in Berlin, was interned during World War I and later managed Derby twice.

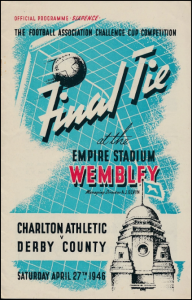

His old club played top flight football between 1926 and 1953. George Jobey’s inter-War sides consistently challenged for honours but never actually won anything; Jobey’s successor Stuart McMillan did rather better, securing the 1946 FA Cup thanks largely to astute signings Raich Carter and Peter Doherty. But times were changing. Derby went down in 1953, and – after a salutary season playing regional football – became perennial members of Division Two.

They were still quietly stagnating when Brian Clough and his assistant Peter Taylor arrived from Hartlepools in 1967. Promotion quickly followed, and then the 1972 League title. Only questionable refereeing against Juventus denied them a European Cup final appearance, but Clough and Taylor – who had frequently quarrelled with abrasive chairman Sam Longson – resigned after six eventful years.

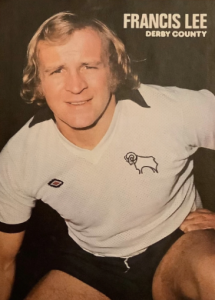

Clough’s side continued to do well under erstwhile skipper Dave Mackay. They won another championship, then challenged for the 1976 Double. But this proved an ageing side’s swansong, and Derby were headed for Division Three when we went there with Telford in 1984. Even so, 22,000 floodlit faces – framed by wintry darkness and piled up snow – made it one of the most atmospheric games I have ever seen.

Click here to see the highlights.

The journey

As usual when heading east we imposed on the elderly citizens of Keele. Kieran was driving John to our meeting place, and asked me for its address; I gave him the wrong one, so they unfortunately spent some little time touring Longton and a housing estate that used to be the Victoria Ground. I blame Stoke City Council for not naming their roads more imaginatively.

The ground

Local landowner Sir Francis Ley loved baseball. He regarded this evolving American sport as ideal summer recreation for workers at his Vulcan Street foundry. Their team – which included Steve Bloomer – had its own specially-designed stadium, and regularly won a short-lived national league that Ley set up. County – who had originally played at the Derbyshire cricket ground – began sharing with them in 1895.

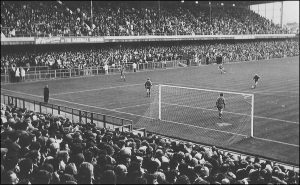

Baseball sightlines proved ill-suited for football. Subsequent modifications – made after Derby purchased the ground outright – merely perpetuated its curiously lopsided appearance. Double-decker stands (“Osmaston” and Normanton”) were built behind each goal, while Archibald Leitch designed a modestly handsome structure than ran along Shaftesbury Crescent.

The Popular Side shared its back wall with Ley’s foundry. This cramped terrace was long favoured by Derby’s more passionate supporters. Clough’s ambitious plans necessitated more seating here, and he involved himself in negotiations to acquire the necessary land. Even then, an impressive new stand – diplomatically named after Ley – could only be accessed via raised walkways at one end.

Visitors were thoughtfully provided with their own Popside enclosure. Entering this pleasant space involved home and away spectators queuing along each side of an improvised segregation barrier, pounding its flimsy corrugated iron while missiles flew overhead. Ninety minutes’ equally uncomfortable proximity followed; the shellshocked travellers would then be funnelled by unsympathetic police along equally menacing alleyways behind derelict houses on Colombo Street.

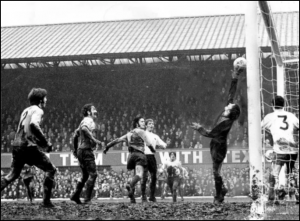

Baseball Ground legends persist longer than most. Seventies players really did wade through mud so cloying that a penalty spot once needed repainting mid-match; other equally notorious episodes – Franny Lee attacking Norman Hunter like some whirling dervish, that Gary Lineker hat-trick ruled out after Burton’s goalkeeper was nearly decapitated by Leicester fans – help explain why the old place holds such poignant memories for many people.

Coaches used to park along Osmaston Road and the nearby industrial estate. Away fans then walked down Shaftesbury Street and Colombo Street – in later years cleared of houses – to their turnstiles. Most avoided the direct route via Cambridge Street. Derby supporters might have enjoyed watching football hemmed in by factories and narrow streets; others were less sure.

New perimeter fencing greeted us in 1984. These modifications stemmed from some unpleasantness the previous season. Derby had secured Second Division survival by beating promotion hopefuls Fulham, but visiting manager Malcolm Macdonald was less than happy as thousands of people gradually encroached onto the pitch. He took even greater offence after they invaded it en masse and a traumatised referee blew for time two minutes early.

None of this was ever going to survive Taylor. Seats clumsily added to the Baseball Ground terraces reduced capacity below 20,000; even had this been enough for Derby’s overblown 1990s ambitions, many fans now demanded less visceral facilities. When they duly relocated in 1996 it was to Pride Park, a vast commercial redevelopment of land formerly occupied by (among others) Chaddesden goods sidings and the Locomotive Works.

Pride Park is basically Middlesbrough’s Riverside surrounded by shops and without a river. One continuous roof wraps around the tall main stand, sloping up to join it on either side. Both goal-end covers angle artificially high above their respective corner flags; one shelters balconies for corporate guests. Such quirks save this ground from the monotonous bowl effect that mars other Sky-era new builds.

You get to admire plenty of retail premises while sitting in gridlocked traffic after the game. I believe football architecture merely reflects social context; shopping-centre stadia can reasonably be considered the spiritual successors of Victorian grounds crowded by heavy industry and workers’ houses. Pride Park – bland or not – shouldn’t be criticised for simply mirroring its social context.

We diverted along Cambridge Street afterwards. It leads nowhere. Haphazard new housing peppers Shaftesbury Crescent’s mutilated remains; you can still identify a curved sweep from the Osmaston Stand corner, but terraced homes that faced Leitch’s classically simple players’ entrance have been demolished. Ugly modern units, meanwhile, cover the site of Ley’s hulking foundry. One solitary section of brick wall remains.

Flesh and wine

The Baseball Hotel has long gone. It was a massive Victorian boozer – memorably described by one Palace fan as “full of hard-looking old men drinking pints of tar” – that stood where Vulcan Street meets Shaftesbury Crescent. Other home pubs worth avoiding included the Vulcan Arms (which remains open) and Cambridge Hotel, both on Dairy House Road.

To the Merlin then. This distinctly non-Arthurian establishment – actually named after Spitfire engines made at nearby Nightingale Road – was full of kids, young men with really big beards and bewildered families trying to order food. We stood by its play park, nursing plastic pints; middle-aged Derby supporters surrounding us looked as though they might have had a few tales to tell.

All new grounds are about maximising retail opportunities. Pies from the concourse bars cost £4; this seemed a touch extortionate, and – adding insult to injury – left me still hungry. By way of compensation the pork roll I bought outside afterwards contained half a pig and my own weight in stuffing (clubs rip us off at every turn, but post-match food vans still represent excellent value. They want to use up stock so you end up with bigger rations for less outlay).

The match

This slow-paced stalemate suggested that neither team will trouble the promotion places. Derby – who were marginally more adventurous – won a penalty shortly before half-time, only to see Martin Waghorn shoot straight at Freddie Woodman. Other misses followed with Waghorn again wasteful; Nathan Dyer, Borja Baston and Sam Surridge also fumbled good chances for Swansea. Some lads behind us decamped to the concourse bar and only came back when it closed. You couldn’t blame them.

Teams and goals

Derby: Roos, Bogle (Lowe 54), Keogh, Clarke, Malone, Dowell, Huddlestone, Evans (Paterson 45), Jozefzoon (Marriott 80), Waghorn, Lawrence. Unused subs: Shinnie, Hamer, Bennett, Davies.

Swansea: Woodman, Roberts, van der Hoorn, Rodon, Bidwell, Fulton, Grimes, Dyer (Peterson 62), Celina, Kalulu (Dhanda 62), Baston (Surridge 68). Unused subs: Nordfeldt, Wilmot, Naughton, Byers.

Attendance: 27,337