Coventry City 2 Rochdale 1

League 1

Saturday 16 November 2019

The context

Another home ground for Coventry. The reasons for their present nomadic existence may be complex, but fans find themselves being royally shafted – and a big part of football heritage systematically destroyed – as yet one more club suffers under dubious ownership. It seems incredible that such things continue to happen.

Kieran and I had some good times drinking with City supporters at the 2018 League 2 play off final. They certainly don’t deserve any of this nonsense. So I’ll concentrate on St Andrew’s for now, and save Coventry’s unique history until another day.

The history

Modern matchgoers never saw Birmingham’s finest performing sinisterly nonchalant circuits around the Rotunda and Bull Ring. Assorted likely lads would slink from the Bar St Martin or Station Hotel, snapping at your jumpy escort’s heels; Bordesley arches on some grey, gritty winter Saturday always felt like a point of no return. Dingy side streets and dead ends awaited those foolish or panicked enough to get separated.

1980s Birmingham had been hit harder than most by the twin evils of post-War urban planning and Thatcherite economics. Neither particularly improved its appearance. Once freed from New Street’s concrete awfulness, however, you could still find fascinating – if grim – beauty in widespread industrial decay and still-functioning Victorian railway infrastructure. Plenty of both could be seen on the two-mile march to St Andrew’s..

Bordesley was once an important section of the Paddington-Birkenhead line. Extensive marshalling yards lined Bolton Road, while cattle sidings – for livestock en route to Digbeth and Deritend markets – made use of the half-built Duddeston Viaduct spur. This still curves hopefully towards Saltley; it would have connected Small Heath with every major rail route in Birmingham.

Northbound trains carried on to Moor Street This had opened in 1909 so that local services could terminate short of the larger Snow Hill station, relieving congestion for express traffic using a narrow tunnel connecting the two. Its adjacent yard handled produce for Bull Ring fruit and vegetable sellers; another nearby goods station occupied the site of Birmingham’s first terminus at Curzon Street.

Snow Hill’s premature closure was controversially short-sighted. Deliberate neglect, combined with the decision to electrify New Street – unsympathetically modernised between 1964 and 1966 – resulted in needless destruction of its ornate Edwardian architecture. Moor Street only narrowly avoided a similar fate, and insult met injury when British Rail opened dreadful modern replacements for both stations just ten years later.

Back to St Andrew’s. Many pre-Taylor grounds were intimidating, but those faded stands glowered with singular menace over Birmingham’s distant skyline. One policeman described it as “The most desolate, scruffy, windy place I ever visited.” Debris-strewn wasteland abounded, while crucifixes dangled bizarrely from each floodlight pylon to counter a curse that ever-rational manager Ron Saunders believed had been affecting the team’s form.

Every story has two sides. Simon Inglis described St Andrew’s as “grim and proletarian”, but reluctant envy can be detected in his Villa-supporting, grammar-school rejection of things he could never quite understand. Old St Andrew’s was a true peoples’ palace. City’s frequent underdog status aroused passionate loyalty and – however territorial – genuine community spirit. So what if parochialism sometimes produced consequences outsiders might not like? No-one forced them to come.

It surprised no-one when a troubled era’s biggest and bloodiest showdown took place here. Full time at Blues’ Second Division promotion game on 11 May 1985 pitched 8,000 nihilistic Leeds fans against every lunatic in South Birmingham. Overcrowding, disorganised policing and sheer, brutal malice produced horrifying violence. One died and five hundred were injured, but these events would prove – mercifully – the high-water mark of two decades’ nasty, insidious one-upmanship that only ever served to demonise working-class culture.

The journey

Not too far for any of us. John once had a delivery round in Birmingham, so ended up as designated driver. He paid us back by making sure our circuitous route incorporated various favourite places from his mis-spent youth, including the Eagle & Tun behind Curzon Street yard (you can probably see him drinking Ansell’s mild with Pato Banton on UB40’s Red Red Wine video).

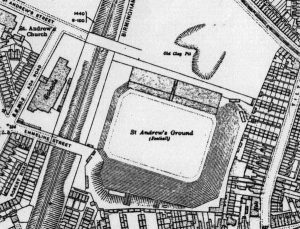

Coventry aren’t getting big gates. Everything felt relaxed as players emerged from cars and early arrivals chased autographs. We parked on one corner of Ada Road – now stopped-up – which ran behind the old City Stand to turnstiles facing Emmeline Street. This stand became the Leeds riot’s epicentre, with most of a school playground being reduced to rubble and thrown at police.

The ground

St Andrew’s still occupies much the same footprint as when it opened in 1906. Such spacious surroundings must have felt like luxury after Birmingham FC’s previous cramped home at Muntz Street. Construction work was delayed by a lively falling-out with some gipsy workmen over their dead horse, which ended up beneath the Tilton End foundations and gave rise to that famous curse.

Today’s Kop and Tilton stands actually comprise one single structure. Its L-shape follows the profile of similarly-shaped former terraces. Birmingham’s enormous Kop – built into earth banking created from excavation spoil – was situated down one touchline rather than behind a goal. Coventry Road’s slope necessitated street level entrances on Tilton Road, and staircases where the terrain fell away towards Emmeline Street.

Birmingham’s popular side enjoyed unsettling opponents. “You couldn’t hear them sing. Their arms moved and pointed, but the Spion just drowned them out”, says one fan of a 1982 derby match. Visitors, meanwhile, were caged next to the main stand. Steel fencing separated us from hostile natives, while low roof girders could equally well be climbed by errant youths or cause head injuries during goal celebrations.

The away end’s topmost corner had been reprofiled some years before. Narrow steps descended from level ground behind it towards some exit gates, with their first flight built at right angles to a boundary wall. This cramped pinch-point provided 1985’s defining tragedy. As the ground finally cleared, dozens of Leeds fans were caught between police – batoning them from behind – and two crumbling brick courses. Everything collapsed outwards onto innocent bystanders sheltering underneath.

A simple Main Stand closely resembles West Brom’s erstwhile Rainbow. Its modern neighbour – which replaced the 1960s-era City Stand – appears much taller than necessary, while encroaching so far onto Emmeline Street that no room remains for any turnstiles. This former hive of (not always respectable) activity now feels completely forgotten.

Flesh and wine

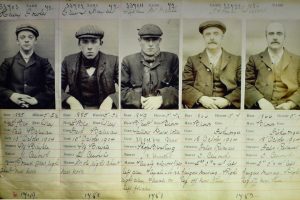

History books describe how hooligans known as Peaky Blinders caused trouble around Small Heath in Victorian times. That wasn’t particularly unusual; most cities had their delinquent folk-devils – Scuttlers from Manchester, Liverpool’s Corner Boys, the Glaswegian Penny Mobs. But television has now made them national causes celebre and iconic representatives of Birmingham itself.

Those original Peakys were no more than street roughs and petty criminals. The TV series owes more to 1920s racecourse turf wars, specifically Billy Kimber’s gang. Kimber came from Newtown. His influence eventually reached London; here he took on Jewish mobster Edward Emmanuel and the Italian, “Darby” Sabini. Police eventually arrested most of his followers after they brutally attacked a coachload of Leeds bookies at Epsom – mistaking them for Italians – and then hid in the nearest pub.

Morphing two unconnected legends most notably resulted in Aston Villa’s star player sporting a daft haircut made famous by fictional Depression-era fans of his club’s deadly rivals. Equally irrational Shelby-themed aberrations now pop up all over the place. Some particularly shocking examples can be found near St Andrew’s, but two landmarks do have genuine history. The Garrison and Marquis of Lorne – now Roost – were once real-life Peaky boozers.

We found the former boarded up. Maybe Kimber’s boys had been round. Livelier elements among Coventry’s diasporic fans were holed up at the ertstwhile Marquis; their mobile disco filled one corner of its Victorian tap room, where everyone bounced around to Tom Hark while inventing insulting lyrics about Aston Villa, Wasps RFC, owners Sisu and Coventry City Council.

None of us fancied beer garden chips and burgers. We opted instead for traditional food van fare, served up as ever by a grumpy yet golden-hearted Brummie sourpuss. Today’s crowd – added bonus, this – proved so sparse that second-helping half time concourse pies were obtainable without queuing. Things could have turned out far worse.

The game

Third-placed Coventry were up against a Rochdale side in lower mid-table. I still find it difficult to compute Dale without Keith Hill managing them, and even less believable that the man who now does so calls himself Brian Barry-Murphy. But – hyphen notwithstanding – he set his side up well, and they went deservedly ahead when skipper Ian Henderson stroked Callum Camps’ excellent cross past Marko Marosi.

Inconsequential feinting and parrying ensued before Jordan Shipley equalised from Zain Westbrooke’s deep ball. Robert Sanchez blocked the first effort, but Rochdale defenders ran about like headless chickens and obligingly invited Shipley to try again. City dominated thereafter. All three points were secured by a Liam Walsh masterpiece of mazy running and defender-beating, emphatically finished with his left-footed rocket high into the Tilton End net.

Teams and goals

Coventry: Marosi, Rose, Hyam, Drysdale, Dabo, Eccles (O’Hare 88), Walsh, Mason, Westbrooke, Bakayoko, Shipley. Unused subs: Watson, Allen, Wilson, Kastaneer, Bapaga, Burrows.

Rochdale: Sanchez, Keohane, O’Connell, Williams, Done, Camps, Ryan (Tavares 78), Morley, Wilbraham (Andrew 81), Hendereson, Pyke. Unused subs: McShane, Baah, Gillam, Hopper.

Goals: Coventry: Shipley 42, Walsh 72. Rochdale: Henderson 28.

Attendance: 5433.