Mansfield Town 2 Carlisle United 2

League 2

Saturday 1 February 2020

The context

I once shared a flat with a young man from Mansfield. He was passionate about the town and everything that came from there. His favourite things were Mansfield Bitter, Our Lass and T’Stags. The first of these he would bring from home, in cans, a week’s supply at a time. The second we never saw (she was saving herself for the eventual day they would get married). And the third he simply would not shut up about.

passionate

I went with him to a Freight Rover Trophy tie at Gigg Lane. On the way there he was full of tales about Mansfield’s famous hooligans and what they would do to any Bury rivals foolish enough to show up. (This gang was apparently known as the Psycho Express and went to games on a double-decker bus with the seats removed.) I had my doubts, but exactly as predicted a mob of Fila-clad Notts youths turned up midway through the first half and casually ran a few dozen Shakers fans out of the Manchester Road End. As dramatic entrances go it was pretty impressive.

The history

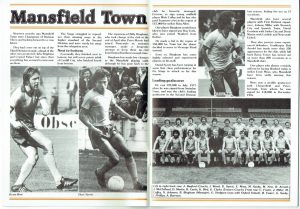

1970s Mansfield must have had something that made folk reluctant to leave. In that decade the Stags’ three record appearance-holders – a goalkeeper and two defenders – racked up 1500 games between them. This consistency underpinned an unprecedented period of success. Between 1968 and 1978 the team enjoyed two runs to the later rounds of the Cup, won the Third and Fourth Divisions and played in the Second for the first and only time. It was by far the most significant spell in their history. But competing with the likes of Tottenham and Southampton proved a step too far and relegation was the inevitable outcome of a difficult 1977-78 season. By 1980 they were back in Division Four.

This was an era of regular highs and occasional deep lows. A 5-1 Cup thraiping by the amateurs of Tow Law in 1967 was followed two years later by a 3-0 triumph over West Ham – including Moore, Hurst and Peters – and a quarter-final against Leicester. The Third Division championship season also featured a humiliating five-goal defeat to non-League Matlock. Into this mixed-up world walked the long-serving triumvirate of Sandy Pate, Kevin Bird and Rod Arnold. Pate arrived from Watford in 1967 and Bird from Doncaster in 1972. Arnold had been understudy to Phil Parkes at Molineux and spent time on loan at Field Mill during 1970-71. He signed on a permanent basis in 1973 and soon replaced Graham Brown as first-choice ‘keeper.

In our day, though, it was all about t’Freight Rover. The erstwhile Associate Members’ Cup was very popular just then with fans of lower-league clubs, not least because it gave them the chance to visit Wembley at a time when few teams ever got to play there. The 1986 showpiece featured the comparative giants of Bolton and Bristol City in a game watched by 55,000, while the 1988 final between Wolves and Burnley would pack in an astonishing 80,000. Mansfield had reached the semis in 1985 as a Fourth Division team (they lost to Wigan). Now Ian Greaves’ men were comfortably back in Division Three and wanted a piece of the action.

Greaves took charge at Field Mill in early 1983. He inherited a team that was, as the phrase goes, languishing. They continued to languish until 1985-86 when a classic blend of youth and experience were promoted in third place behind Swindon and Chester. I can still name the spine of that side – shot-stopper Kevin Hitchcock, defensive stalwarts George Foster and Mike Graham, midfield pivots Tony Lowery and Mark Kearney, goalscorers Keith Cassells and Neville Chamberlain. They were a resilient bunch and this solidity grew in the higher league. Between August 1986 and the turn of the year the Stags lost just three times.

1986-87: Chester City 1-0 Mansfield Town (Freight Rover Trophy)

April 1987 – Colin Woodthorpe’s free-kick gives Chester victory on the night but it’s Mansfield celebrating at the end as they go through to Wembley with a 2…

The Freight Rover featured a confusing format of ever-decreasing group stages, straight knockouts and two-legged ties. By March Mansfield had eliminated Halifax, Rotherham, York and Bury and found themselves in a straightener with champions-elect Middlesbrough at Ayresome Park. A coolly-taken Kearney penalty fifteen minutes from time decided a combative game. The reward was a double-headed semi with Chester that the Stags won 2-1 on aggregate. You can see highlights of the nerve-jangling second leg above. This was contested in front of a packed, simmering crowd of over 8000. No players were rested and no game management took place.

Sixty-odd thousand went to Wembley for the final. They saw Mansfield soak up an hour’s pressure from holders Bristol City before Kevin Kent ghosted onto a Cassells cross for 1-0. It stayed that way until a scrambled Glynn Riley equaliser in the dying seconds. Extra time was goalless. The penalty shoot-out started well but took a nasty turn when a Cassells miss left Hitchcock needing to save from Gordon Owen. He cleared the ball with his feet, Kent levelled at 4-4, Hitchcock saved more convincingly from David Moyes’ sudden-death kick and Tony Kenworthy won the trophy with a true defender’s effort. “Wembley Wonders”, understated the local Chad newspaper.

The journey

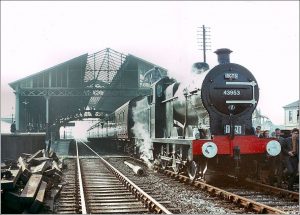

We hit heavy traffic on our last trip here and ended up at Derby instead. But today we were soon parking for a couple of quid next to Titchfield Park after an easy drive cross-country from Stoke. (The River Maun runs through this park. It isn’t clear why we weren’t therefore in Maunsfield.) Many visitors to Field Mill go by train because Mansfield station is a mere quarter of a mile away, but until it reopened in 1995 the closest you could get was the misleadingly-named Mansfield & Alfreton Parkway. This wasn’t in Mansfield at all but eight miles away in Alfreton, a minor detail which occasionally caused tensions when visiting fans got off there expecting the ground to be somewhere nearby.

The station is a Grade II listed building. It used to be called Mansfield Town (this line was on the LNER, while the long-gone Mansfield Central served the LMS). A near-century of history ended in 1964 as a consequence of Beeching’s well thought-out railway reforms, although coal trains still passed through to serve the collieries that once filled this area. The mines are all gone now – only a couple of commemorative headstocks remain, along with a lot of landscaping and plenty of residual bitterness. The miners’ strike was a sensitive subject in our flat and even now it’s still best not to mention Arthur Scargill round here. Especially when Chesterfield are the visitors.

The ground

Field Mill is the oldest ground still in use for professional football. That’s not to say there aren’t older ones, or that others haven’t staged professional football for longer. But the fact remains it was built in 1861 and football has been played there more or less continuously ever since. In those early days it was a general purpose sports facility for the nearby Greenhalgh Works and home variously to Greenhalgh FC, Field Mill FC, Mansfield Greenhalgh and Mansfield Mechanics. The Stags took possession in 1919. A grandstand went up during 1922, to be joined seven years later by another, smaller stand on the Bishop Street side. The second of these stands was superseded in 1937 by a more substantial version that survives (just about) to the present day.

The former running track was used briefly for greyhound racing between 1928-30. When concrete terraces eventually replaced the original cinders they were folded around the same elliptical profile. A cover was added to the northern terrace in the 1950s and this became the traditional “home” end until 1999, when three sides of the ground were flattened and rebuilt with modern all-seated stands. The exception was the Bishop Street Stand, left in solitary splendour and flanked by disused terracing (redevelopment is tricky along this side because of the steeply sloping streets behind). This old stand is a sorry sight. It’s been condemned and boarded up since 2006 and now does service as a huge advertising hoarding.

There’s no doubt the rash of stand construction that followed the Taylor Report swept away a number of outdated, unsuitable and downright dangerous structures. But the folk-panic over terraces also allowed some serious vandalism to take place. That was certainly the case when Field Mill’s West Stand was pulled down in a fit of rebuilding zeal. The stand had been transplanted whole in 1959 from the soon-to-close Hurst Park racecourse in Surrey, and featured gloriously delicate Art-Deco detailing and a roof similar to those at Highbury (Simon Inglis described this as resembling an upside-down paper boat). If Mansfield railway station was worth listing then this lovely building also deserved to be saved.

North pole (Mansfield Town FC)

Architectural merit was something neither terraced end possessed. The Quarry Lane was a typically spartan visitors’ enclosure with the invariable fiendish twist, in this case turnstiles adjoining the home fans’ social club. The terracing formed a narrow curving wedge like a truncated slice of Edam. It lacked any form of shelter apart from the tin roof on some basic toilets. The North Stand behind the opposite goal had a similar shape but boasted a pitched asbestos roof, with an advertisement board and a clock at its centre. (On the subject of adverts, a visit to Field Mill always generated conversation about what “Chad” actually was. It’s an amalgam of ‘Chronicle’ and ‘Advertiser’. Pay attention, there’s a quiz at the end.)

Systematic levelling of surrounding houses and factories has left Mansfield’s home isolated and yet heavy with memories. The public footpath behind the houses on Lord Street was, until 1939, the route taken by players from their improvised dressing rooms in the now-demolished Bull’s Head Inn on the corner of High Street and Portland Street. The retail park overlooking the North Stand is the site of Greenhalgh’s threadworks. These links with the past help the ground retain a certain presence. Its hilltop position dominates the town centre and allows the main Ian Greaves Stand in particular to appear larger than it actually is, while the raised practice pitches opposite the main entrance are a touch of Seventies class redolent of Elland Road in its glory days.

Flesh and wine

There aren’t many food and drink options on the surrounding retail parks. Although this was once the centre of Sherwood Forest you’re now more likely to see Papa John’s than Little John. The nearest pub to Field Mill is the Railway on Station Street. This presumably suffered a serious identity crisis throughout the Seventies and Eighties. It seemed friendly in an understated kind of way, had a pleasant family vibe and was in favour with the pre-match pie and chips brigade – but not with John, who complained they had too much real ale and not enough bottled lager.

He soon cheered up when we spotted a burger stall outside the Ian Greaves Stand. The area between the turnstiles and the practice pitches also contained a gin hut and the Sandy Pate Bar. This establishment commemorates the famous Scottish right-back who played for the Stags nearly 500 times between 1967 and 1978. Pate came to notice as a member of the Third Division side that reached the FA Cup 6th Round in 1969, and – like Bird and Arnold – went on to become a fixture for a seven year spell that spanned both title wins and the Second Division season. The bar’s location in the back of the stand appeals to last-minute drinkers. They were being helped through the turnstiles by a sniffer dog, which was meant to be looking for drugs but only managed to find a carton of chips John had concealed under his coat.

The game

We sat in the upper tier and had a fine view both of Dunelm Mill and the remains of the Bishop Street Stand. Our neighbours were Mansfield’s singers, drummers and bouncers. The end block remained empty to increase the distance between these zealots and three hundred-odd Carlisle fans behind the goal. But there was no sign of the Psycho Express. As most will be knocking sixty nowadays they were probably in Dunelm Mill.

The first half was awful. This was a match between two sides not far above the one remaining relegation place. Carlisle – wearing one of those mint-green strips strangely in vogue this season – marginally had the better of things, although it was hard to avoid a sense of two bald men fighting over a comb.

Matters improved a little after the break. Mansfield now had the considerable wind behind them and Nicky Maynard bagged a couple of decent strikes, both low finishes following good approach play from Danny Rose. And that, given Carlisle’s general toothlessness, should have been that – but cometh the hour, cometh Elliott Watt. The on-loan Wolves midfielder scored a cracker with seven minutes to go, a dipping and possibly wind-assisted curler. All of a sudden the Stags were on the back, er, hoof, and it all went horribly wrong for them in the third minute of added time when Watt sent a low free-kick into the box which Joshua Kayode scuffed in from close range.

How the fans grumbled.

Teams and goals

Mansfield: Olejnik, Watts, Pearce, Sweeney, Riley, Bishop, MacDonald (Tomlinson 22), Benning, Charsley (Hamilton 77), Rose, Maynard (Preston 88). Unused subs: Davies, Clarke, Knowles, Stone.

Carlisle: Collin, Jones, Webster, Hayden, Wilmer-Anderton, Bridge (Guy 59), Jones, Watt, Thomas (Scougall 86), Allesandra (McKirdy 59), Kayode. Unused subs: Iredale, Charters, Gray, Hunt.

Goals: Mansfield: Maynard 58, 72: Carlisle: Watt 81, Kayode 90+3.

Attendance: 4272.