Stade Brestois 29 2 LB Chateauroux 3

Ligue 2

28 July 2017

le Telegramme

The context

You know how it sometimes happens that you’re on holiday and begin wondering idly if any games are on nearby? This was where we found ourselves. It turned out that Brittany’s big two, Nantes and Rennes, had nothing happening save for reserve friendlies against lower division sides. But luckily the French second tier starts earlier than Ligue 1, in July rather than August, and the region has a couple of teams in this division. Lorient and Brest are an easy if rather monotonous journey on the tidy French motorway system and Brest were at home, in a typically Gallic Friday evening kick off, for the opening game of the Dominos Pizza-sponsored Ligue 2.

The history

Many French football clubs use the name “Stade”. These originally comprised a number of different sports teams and were often founded by students or academics. The enigmatic “29”, meanwhile, is down to Brest’s location in Finistere, the 29me Department. Les Ty’Zefs were formed in 1950 when one Canon Balbous merged five Catholic patronages and, by extension, their sporting arms. The new club took over the fixtures of L’Armoricaine de Brest – Armorica is the ancient name for Brittany – and played at their Stade de l’Armoricaine in the Petit Paris district. L’Armoricaine had been founded by another priest, Father Cozanet, 28 years previously. The ground suffered extensive damage during the War and a small but dedicated band of volunteers rebuilt it following the Liberation.

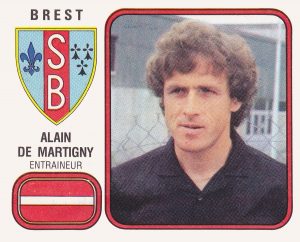

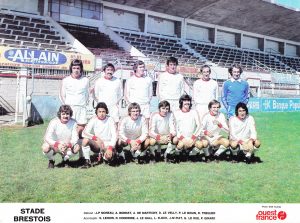

Brest’s success in the modern era owes much to two key personalities. The first, local electricity supplier Michel Bannaire, became President in 1976. His ambition was to take them to Ligue 1 and he saw Alain de Martigny as the man to do it. The Lille sweeper was only 29, young for a player-coach but with a reputation as one of the game’s intellectuals. He’d been a teacher before turning professional and was known as a clever tactician, a hard worker and a strong tackler. Director of football Rene Charlot secretly met the libero in Hazebrouck that February. The two agreed that De Martigny would come to Brest in 1976-77 even if, as seemed likely, the team were relegated from Ligue 2.

a new beginning (SB29)

In the event they stayed up with a win on the last day and De Martigny began his rebuilding job with a pair of marquee signings. As well as ending the club’s amateur status, Serge Lenoir and Louis Floch were of an age where they could offer both vigour and experience. Midfielder Lenoir had been a Cup winner with Rennes and returned to his native Brittany from a Bastia side that reached the UEFA Cup final the following season. Floch, also a Breton, settled rather better. He was an effusive character with sixteen caps who scored prolifically at Rennes, Monaco, Paris and PSG but became a playmaker at L’Amoricaine, where the rumble of “Loulou, Loulou” from the stands would soon be a familiar sound.

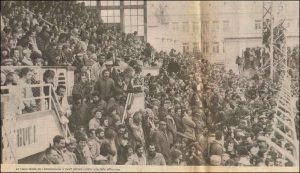

De Martigny’s revolution reached its zenith on a warm evening in April 1979 when Ligue 2 leaders Brest took on second-placed Lens. The game was effectively a promotion cup final and its official crowd of 18,080 is disputed by those who believe nearer 25,000 had packed into the creaking old stadium. Supporters perched on fences, pylons and roofs and saw the home team win 3-1 with goals from Kedie, Hedoire and an 18 year-old Yvon Le Roux. Loulou Floch summed up the occasion’s joyful anarchy when he recalled how the dressing room was invaded by Lens fans after the game. “They wished us no harm, they just wanted to congratulate us. They came into our locker room and joined the party! It was special.”

Le Roux was the first of many players to make the grade at Brest, starting as a schoolboy and eventually returning as manager after a career at Monaco, Nantes, Marseille and PSG during which he won 28 caps and starred in the 1984 European Championships. He attributes much of this success to Floch. With typical generosity the old pro took the youngster under his wing at Stade de l’Armoricaine. During the drive to training in Floch’s Mercedes the two would talk football, football and more football. “He told me about his career and the challenges of the professional game”, remembers Le Roux. “Loulou was very important for my development. He’s a bit of a big brother to me. And big brothers inspire us.”

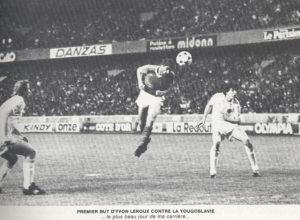

The historic first top flight season that followed was notable for a string of stunning performances from Drago Valbec. The Yugoslav international joined from Dinamo Zagreb in the summer and scored 17 goals. But apart from this small consolation it proved a humbling experience as the team finished bottom. De Martigny produced another Ligue 2 winning side in 1980-81 and then left following a quarrel with new president Francois Yvinec. He embarked on a nomadic tour taking in RC Paris, African football, the Gabon national team, Guingamp, Angers and Meaux, returning to a becalmed Brest in 1999 and leading them out of the fourth tier in his final years as a manager.

There have been other internationals. Paraguayan striker Roberto Cabanas achieved cult status by scoring 53 goals in the 1988-89 Ligue 2-winning year and the Ligue 1 season that followed. Stephane Guivarc’h made his debut as a 19 year-old in 1989. David Ginola, meanwhile, spent two years in Brittany during the early 1990s in a typically turbulent spell for the Ty’Zefs, winning most of his caps while at the club. And Franck Ribery started here as an amateur in 2002-03. For all their ups and downs Brest have overachieved more often than not, a legacy entirely due to De Martigny. As Loulou Floch remarked, “With another trainer it would not have happened. It was Alain who brought all this.”

The set-up that welcomed the newcomers in 1976 was far from glamorous. Floch recalled a dressing-room with an earth floor and a playing surface more mud than grass. The ground had altered little since an early Sixties upgrade. Its pride and joy was the small but tidy Pen Huel stand on the western side, with the Breton motto – “Head Held High” – painted in the centre. There was a covered terrace opposite, known as the Tribune Foucauld after a nearby school. The team trained on a practice pitch behind this, or at the Lann Rohou golf course at Landerneau. “It was practically the same stadium I experienced with Saint Pol in 1964”, said Floch. “We preferred to play away, on better pitches.”

Despite its shortcomings L’Armoricaine was occasionally called upon to stage home matches for other local teams. In 1966 the village side Stade Briochin, from nearby St Brieuc, took on and sensationally beat Marseille there in the Coupe de France. And in 1973 the ground was used by En Avant Guingamp during another record-breaking Cup run, ironically after they had beaten Brest in an earlier round. The tie between the Rouge et Noir and the full-timers of Lorient anticipated the Lens game for intensity and a casual approach to crowd control. The occasion ended in similar scenes, too, as the tiny Cotes d’Armor team beat their bigger neighbours to earn another derby with Stade Rennais.

But fame costs and so too does Ligue 1 football. 1982 proved the point of no return for the old l’Armoricaine. The city council took over the stadium and renamed it after recently deceased former mayor and keen Brestois fan, Francis Le Ble. The Foucauld terrace was demolished, to be replaced with a new 10,000 capacity stand that also obliterated the training pitch. The Pen Huel survived until 2010 before giving way to a substantial but bland prefabrication hastily built during the club’s last spell in the top flight, while a smaller and more ricketty counterpart went up at the Rue de Quimper end. Opposite this appeared an even more basic and exposed tubular construction, known – with disarming honesty – as the Tribune Plein Ciel.

The visit

Brest is twinned with Plymouth. It’s an appropriate pairing – both are dockyard cities, whose mediaeval street plans were obliterated by wartime air raids and replaced in the Fifties and Sixties by broad open boulevards and brutalist architecture. The bombs that flattened l’Armoricaine were intended for the nearby naval base. A similar fate befell various other ports on this coast used by the Germans for their U-boats such as La Pallice, La Rochelle and St Nazaire. The French Navy remains key to the local economy but there were no warships to be seen today, other than the antiques in the maritime museum at Brest Arsenal. So we walked across Pont de Decouvrance and looked at the sentries instead.

We’d called at the ground that morning expecting to find some sort of ticket office. This assumption proved false and there was no-one about. The advice from a man with a bicycle was “Revenez plus tard”, but the place was almost equally deserted plus tard. We found only a hot dog van crewed by an elderly Breton sourpuss and a girl with bright orange hair and multiple piercings, who turned out to be a Leicester University student eager to practice her English on us. A gaggle of red-scarved fans slowly gathered outside the Bar Le Penalty and as kick-off time drew near a couple of gendarmes turned up on motorbikes and half-heartedly blocked the road. The turnstiles, however, remained stubbornly closed.

Eventually a few people gathered expectantly near some wooden hatches in the perimeter fence. The shutters were opened from the inside and desultory ticket-buying began. I chatted to one of the fans from Le Penalty. “You come from England to see this football? That’s good. But you must be mad!” We bought tickets for the Tribune de Quimper, as they were cheapest and this seemed the part of the ground most likely to have a good atmosphere. The home fans’ kop resembled a tin shed. The outside was decorated with street art and murals, including one of Cabanas. It’s named after the road running past the ground. Locals, who know the nearby town of Quimper by the Breton name of Kemper, call it the TDK.

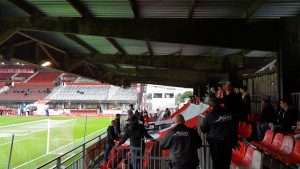

The TDK felt like a welcome throwback to Brest’s amateur days. The forecourt held beer and food caravans where we bought Kronenbourg 1664, the club newspaper and les hotdogs. There was a supporters’ club “shop” selling scarves and keyrings from a trestle table tucked beneath the overhang of the seating tier. Up the steps we found bucket seats bolted to bouncy metal steps, a low claustrophobic roof and a group of ultras laying out flags under the watchful gaze of the Police Nacionale. The chief ultra broke off from directing operations and came over. “You are English? You have been before? Stand to the side, it will be good. When the football begins, that is when things happen here.”

The game

It started to rain as the teams came out. The ultra leader, megaphone in hand, had taken up position on a small platform attached to the steel perimeter fence. From here he choreographed a non-stop loop of chanting and pogo-ing. On the pitch beneath him Chateauroux made a determined start but the home side went in front after thirty minutes, Anthony Weber mis-hitting a low Julian Faussurier cross into the net as the visitors struggled to clear a corner. Brest dominated after that and Faussurier almost doubled the lead just before half time. As the players trooped off the ultra drew a deep breath, put his shirt back on and tucked into a cheese baguette he produced from a Carrefour carrier bag.

The drizzle became a monsoon. Brest led 2-0 on the hour, Bruno Grougi scoring from the spot after Gaetan Belaud had been sliced down by Sidy Sarr. It should all have been over when Haisen Hassam tipped over a superb long-range shot from Edouard Butin. But the Ty’Zefs unravelled. First, Said Benhrama converted a penalty after Kamel Chergui made his dive look good from Faussurier’s challenge. Next, Yannick M’Bone rose superbly to head in an outswinging corner. And then, just as the Brestois were settling for a draw, a superb break ended with sub Sofiane Khadda slotting home in the dying seconds.

The ultras had started the second half with a rendition of Fanny de Laninon, their classic seafaring anthem mourning pre-War Brest. Now the TDK watched silently beneath a pall of steam and Marlboro smoke as a firework, launched from outside the ground, scattered the seven-strong travelling support on the Tribune Plain Ceil. its flames lasted a few brief seconds before the rain put them out and we all splashed off into the night.

Floch wallpaper

Teams and goals:

Brest: Fabri, Weber, Belaud, Bernard, Chardonnet, Grougi, Gastien, Faussurier, Austret, Pi, Butin. Subs used: Berthomier, Labidi.

Chateauroux: Hassan, Angoula, Alhadhur, Mbone, Traore, Tounkara, Benrahma, Sangante, Sarr, Merghem, Chereui. Subs used: Fofana, Neves, Khadda.

Goals: Brest: Weber 30, Grougi 68 (pen). Chateauroux: Benrahma 75 (pen), Mbone 87, Khadda 90+2.

Attendance: 7,571