Salford City 1 Leyton Orient 1

League 2

Saturday 31 August 2019

The context

Around April each year – usually in the car en route to some match or another – we start taking an interest in the upper reaches of the National League table. The non-League promotion shake-up is a big deal for people in the 92 Club, and for those (like us) perpetually on its fringes,

All seemed good at the back end of 2018-19. Our soft-spot holders Orient were nailed on to win back a League Two slot they should never have lost in the first place, with equally solid old-school citizens Wrexham close behind. Of the remainder (and with no disrespect intended), Eastleigh, Fylde and Solihull didn’t appeal either as members of the Football League or as candidates for a decent day out. And Salford? Well, and again being brutally honest, the Ammies were no-one’s first choice – but if push came to shove they were at least convenient to get to, drew decent crowds and lived in a proper city and not a bland suburb.

That said, once Wrexham succumbed to the inevitable we were probably in a minority rooting for the eventual play-off winners. As an exercise in unpopularity Salford City tick boxes for a lot of people. They are perceived as bankrolled, which is hard to deny. Their owners – the so-called “Class of 92” Manchester United players, their cronies and business contacts – trigger strong emotions in many fans, as does their alleged influence in selecting games for live broadcast. And to add insult to injury the club were featured in a high-profile TV documentary series in 2013, an honour not usually afforded to mediocre Northern Premier League outfits.

It’s hard, however, to begrudge any good fortune that befalls this most disadvantaged of Northern cities. There are good reasons why Salford inspired Coronation Street’s Weatherfield. From the Industrial Revolution onwards its poorer districts were known for being unrelentingly grim, poverty-stricken and disrespectful of authority. This was the setting for Ewan MacColl’s classic song Dirty Old Town, and MacColl himself was born a short distance from the present football ground in Andrew Street, Broughton. He overcame the disadvantages of a poor upbringing by schooling himself while keeping warm in Manchester Central Library. In his career as a writer, actor and protest singer he displayed the passionate Socialism of his Scottish parents and the radical traditions of his birthplace.

The history

It would be wrong to imagine that Salford City’s history started in 2014. But sadly a lot of it was destroyed five years before that, when an arson attack at the Moor Lane clubhouse sent all their memoribilia up in flames. (Being charitable, this explains why the three quarters of a century preceding the takeover is condensed into a single paragraph on the official website.) The highlights of that history were proudly amateur, hence the Ammies nickname – most notably, three Lancashire Amateur Cup wins and a brace of Manchester Premier Cup wins in the 70s. The team moved to Moor Lane in 1976. Up until that time they played at Meadow Road, in a loop of the River Irwell close to the city centre.

Moor Lane is the oldest sports ground in Greater Manchester. Its first recorded use for public recreation was in the 1680s, as the start and finish line of Kersal Moor racecourse (the 1930s main stand was built over the cobbles of the opening straight). For centuries Kersal Moor was a place where the poor of Manchester and Salford resorted for public gatherings. Fighting, hangings and duels were among the more popular attractions. In the heyday of the Radical movement it was a haunt of both the Chartists and the military, with an estimated 300,000 people attending a Chartist meeting there in 1838. Last but not least, in the 18th century the Moor staged nude male racing. One of this courtship ritual’s most famous proponents was “Spanking Roger”, the Squire of Moston, later commemorated by having a Miles Platting boozer named after him.

Although Moor Lane was once home to the celebrated Broughton Archers, in later years the site became known for more prosaic pursuits. In the 1880s it staged meetings of the Manchester Athletics Club prior to their relocation to Fallowfield. During the 1920s it was known as Kersal Cricket Ground and hosted the Northern Tennis Tournament. And for 50 years Manchester FC were based there, building the much-missed brutalist main stand during their tenure. Manchester were the city’s oldest rugby union club, and rugby returned between 2002-04 when League side Swinton Lions were briefly tenants during a nomadic phase in their chequered history.

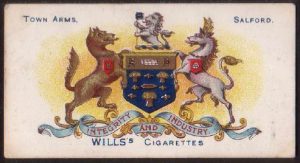

One criticism of the present owners is that they apparently have scant regard for this rich heritage. The now-demolished concrete stand may not have been beautiful or even particularly practical, but it had immense historical and local significance. The old lion rampant badge might not have been unique, but it was taken from the city coat of arms (and didn’t look like Scar from Lion King). And City’s shirts were not always the tangerine colour of 2014, but replacing them with United red was at best insensitive and at worst indicative of an agenda yet to be fully revealed. Fortunately these were not issues for us today. As Louis MacNeice put it, “All the tripper wants is the status quo, cut and dried for trippers.”

The journey

Not much of a one. I had a leisurely drive across the West Pennine Moors and the other two got to travel on the M602, the only existing piece of carriageway from the 1960s South Lancashire Motorway project. This was once going to connect Manchester with Liverpool, but now has to be content with connecting Salford to Eccles.

Moor Lane is off the main road from Manchester to Bury. It felt sadly ironic to visit the League’s nouveau-riche newcomers in a week when the much older but also much poorer club at the other end of that road went out of business. We parked up near The Cliff. For four decades – until Alex Ferguson decided it was a bit too public for his liking – Manchester United’s first team trained here. It had floodlights before Old Trafford itself. In 1952 The Cliff was the setting for the biggest win in the history of the FA Youth Cup, when a team of United youngsters steamrollered Nantwich Town and David Pegg, John Doherty and Duncan Edwards scored five goals each and Eddie Lewis four in a 23–0 victory.

The ground

Some clubs, faced with the need to update facilities, adopt a progressive approach and develop their grounds over a period of years and even decades. This panders to the often conservative nature of the average supporter and allows those creatures of habit to adapt gradually to new surroundings. Others decide to make a completely fresh start and uproot to a totally new site. These build something cheaper and nastier but far more low-maintenance, leaving the fans to simply get on with it.

The ones who can afford it, meanwhile, go for a “solution” – the football equivalent of getting an extension built while you’re away on holiday. Salford unsurprisingly chose this option. You can see the story of the project, and its outcome, here:

jmarchitects – Projects

The brief was for a 5000 capacity stadium, split across four stands, with standing stands behind the goals and two fully seated stands along both sides of the pitch. The scheme included new facilities such as a fanzone, hospitality areas and improved back of house club accommodation, in addition to new floodlighting in line with the current FA regulations.

Salford’s ground prior to 2017 was an irregular bowl with a single stand and a wall around the perimeter. The short-term answer to enabling larger crowds and ultimately League football was to demolish the lot and throw up a replacement. This process took less than two years from start to finish, and the result is a tidy ground with a 5,000 capacity – built on the traditional stands at the sides and terraces behind the goals model, but with haphazard bits of terrace among the seats to placate long-time patrons with settled viewing habits. The whole thing is made from prefabricated metal sections but feels surprisingly permanent, possibly because unlike many off-the-shelf stadia it’s surrounded by roads and houses.

This may have felt like a curse to the builders (and to those residents who ended up with chunks of demolished stand in their front gardens), but actually rescues the ground from total blandness and is responsible for such quirks as it has. The bowl shape is still very much evident, so the Moor Lane side is well below street level – this means that access is via a staircase at one end and a sloping path at the other, and allows passers-by to watch the game by peering over a fence and through gaps in the back of the stand. It also gives the pitch a serious side-to-side slope, so pronounced that fans in one corner are level with the playing surface while those at the other are six feet above it.

The corporately-sponsored Peninsula Stadium’s other nod to tradition is that access is lousy. Frankly I imagine this site and its hasty upgrade are short-term measures on the road to a bigger place somewhere more convenient – or possibly a groundshare with Salford Red Devils, whose A.J.Bell Stadium has staged high-profile City friendlies in recent years. But for now the club remain squeezed between Moor Lane and the appropriately-named Nevile Road, with no easy access from one to the other and no obvious place to park away coaches. This resulted in some post-match silliness when an 800-strong Orient following were let out into an unpoliced road full of Salford youths, high on alcopops and bursting with the zeal of converts.

Such is the way with an overnight support base. Although signs implore fans not to bang on the back of the stands (there’s probably a discount for returning them undamaged) we heard plenty of banging and singing from a busy home end as kick off approached. But once the teams were out – to the Pogues version of Dirty Old Town, classily uninterrupted by any announcements – you could have heard a pin drop as the assembled masses settled down to watch the game like a TV audience. Salford’s isn’t your usual lower-league or non-League crowd. That was illustrated perfectly by the sight of a dozen or so fans genuinely perplexed by a far from full terrace, who stood around like lummoxes until a steward pointed out a gangway and suggested they walk up it and find somewhere to watch from.

Flesh and wine

Plenty of options in the centre of Salford, but the ground isn’t in the centre – it’s perched on the very edge of the moor, and what few pubs once existed have mostly succumbed to the millennial curse and are now branches of Dominos. Luckily however I have contacts, and one recommended the Star Inn, a co-operative boozer hidden away down a Broughton backstreet a mere quarter of a mile from the ground. So well-concealed in fact that there were no football fans in it at all, just an eclectic mix of locals and burly fellas who’d knocked off the morning shift, all busy necking Carlsberg and getting annoyed at Manchester United’s abject showing against Southampton on the TV.

Up at the ground it was all about the fanzone. In line with Moor Lane’s impermanent ambience, an al fresco dining and supping experience has been cleverly constructed behind the home end from a strip of concrete and a line of lorry containers. The clientele looked mostly as though they normally watched United, would have preferred to be watching United or actually had been banned from watching United. Some of the containers held portable bars, while others offered different food choices. These included curry, the usual burgers, and various other bits and pieces. Tucked away at one end was an anonymous-looking box labelled simply (and ungrammatically) as ‘Babs’ café’.

Babs was an unexpected star of the TV series, although as most small clubs have a Babs her rise to fame came as no surprise to fans of non-League football. An acid-tongued but golden-hearted tea-hut lady, she was portrayed as a teapot-wielding Ena Sharples, Beatrice to Gary Neville’s Benedict. Babs went through several cafes as the ground was upgraded, finishing up in smart new premises next to the main stand, but nowadays she jostles for space with bad lager and hipster hotdogs. Fortunately the food is unaffected and the ‘café’ serves a decent pie and peas. While I was eating a man spotted a wasp on the back of my shirt and swatted it. After that random act of kindness I also had gravy down my front.

The game

It all started well for Salford, as Richie Towell pounced onto a mishandled throw and punted the ball high into the far corner for an early opener. Indeed the first half hour was all about the Ammies. Brill in the Orient goal was anything but, dropping the ball onto Rooney’s boot for a disallowed second shortly after a cracker from Dieseruvwe had almost crept under his crossbar. But the home side didn’t make their advantage count, and were gradually tamed during a muted second period in which Orient restricted them to the odd half chance. Justice was done late on when Salford ‘keeper Chris Neal committed a comedy error from a corner and backheeled Brophy’s shot into his own net.

“It’s all your fault”, joyfully crowed the O’s fans behind Neal’s goal. But the equaliser had been coming for the best part of an hour, and a draw was undoubtedly fair.

Teams and goals

Salford: Neal, Wiseman, Pond (Threlkeld 50), Piergianni, Touray, Beesley, Maynard, Towell, Lloyd-McGoldrick (Walker 89), Dieseruvwe, Rooney (Jones 76). Unused subs: Letheren, Whitehead, Jones.

Orient: Brill, Coulson (Maguire-Drew 63), Ekpetita, Happe, Ling, Wright, Clay, Brophy (Judd 92), Dennis (Harrold 84), Wilkinson, Angol. Unused subs: Gorman, Sargeant, Marsh, Alabi.

Goals: Salford: Towell 13. Orient: Neal og 87.

Attendance: 3154.