AFC Bournemouth 1 Fulham 0

Premier League

Monday 14 April 2025

Cherries chapter

The context

Our long-awaited 92nd League ground. It was hard to believe after trying for so long. Dean Court’s modest size had made tickets almost impossibly scarce, so John and I – after years of frustration – eventually gave in and trekked here last November for a women’s game. This secured the precious loyalty points that qualified us for tonight’s basic hospitality package.

The history

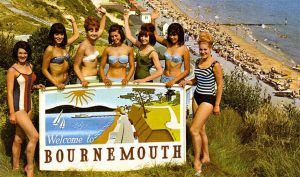

Bournemouth didn’t exist as such until Victorian times. This area was open heathland, frequented only by grazing cattle and an occasional farmer or smuggler. But many such isolated communities became thriving resorts during the late nineteenth century. Before long Thomas Hardy commented on its “glittering novelty” in Tess of the D’Urbervilles as royalty, politicians and well-off thrill-seekers came here to sample sea air.

Railways helped make the seaside accessible. Bournemouth soon had two big stations, East (1870) and West (1874). These connected with the main Waterloo line at Christchurch, while trains also ran cross-country to Bristol via Poole. Population rose from 600 to 60,000; neighbouring villages such as Boscombe, Westbourne and Pokesdown grew equally rapidly, becoming part of a new municipal borough.

East was known as Bournemouth Central after 1899. Most services terminated at West until Beeching wielded his short-sighted axe; the Pines Express ran daily between there and Manchester Mayfield, while dozens of long-distance trains arrived from Northern towns on summer Saturdays. Enthusiasts flocked to see unfamiliar steam locomotives that brought heavy passenger trains over the Somerset & Dorset line’s notorious gradients.

This hundred-mile stretch treated holidaymakers to spectacular views of the Mendips and Somerset Levels. But construction had been tricky, maintenance proved expensive and local services were neither punctual nor profitable. Bournemouth West’s site is still easy to spot off Ashley Road, while Broadstone Way follows the track’s curving route away from Poole towards Blandford Forum.

Many impressive civic buildings were built. Hardy’s rural characters marvelled at piers, pine groves, promenades and covered gardens. The Prince of Wales installed Lillie Langtry, his reputed mistress, at Red House; Mont Dore Hotel residents could take specially-imported Auvergne spring water, and Westbourne Arcade offered high-class shops beneath a covered gallery.

This became the first municipal town to provide regular live music for residents. A huge Winter Gardens – modelled on London’s Crystal Palace – opened in 1893, hosting concerts by Edward Elgar, Hubert Parry, Gustav Holst and Jean Sibelius. Bournemouth Pavilion Theatre regularly staged top West End productions and popular music-hall shows.

Football also thrived. Local team Boscombe had been Southern League members since 1920; they now joined the Football League as Bournemouth & Boscombe Athletic, and would remain a Third Division side for fifty consecutive – if mostly unremarkable – seasons. Their simple ground stood in King’s Park, near the site of Thistledown Barrow and surrounded by sedate public gardens laid out to commemorate Edward VII’s coronation.

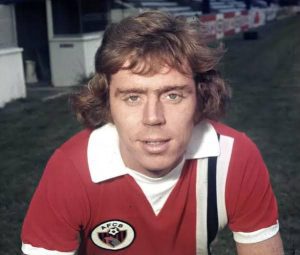

Decades of safe predictability were rudely interrupted by relegation to Division Four in 1970. An entertaining side built by John Bond then went straight back up, with Ted MacDougall and Phil Boyer getting fifty-three goals between them. The pair had been at York together; they subsequently proved just as deadly elsewhere, joining first Bond’s new club Norwich City and then Southampton.

The club celebrated promotion by renaming themselves AFC Bournemouth. An impressionistic new badge – depicting celebrated former player Dickie Dowsett – came next. MacDougall just carried on scoring. He added another thirty-five League goals to his forty-two from 1970-71, along with three hat-tricks in the 11-0 FA Cup rout of non-League Margate.

MacDougall’s diving header at Villa Park on 12 February 1972 thrilled Match of the Day viewers. But a 2-1 defeat left Bournemouth third, which – in days when only two teams went up – would be where they ultimately finished. First Division managers began eyeing him up; Manchester United badly needed a striker, and got their man for £200,000.

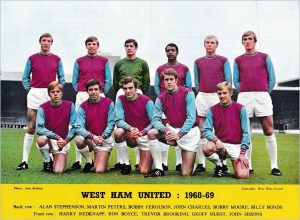

It would be fifteen more years before promotion was finally secured. Its architect – ambitious young manager Harry Redknapp – had played here for four seasons after leaving West Ham in 1972. Redknapp then coached Seattle Sounders, Phoenix Fire and Oxford City. His first season as manager saw Bournemouth memorably knock Manchester United out of the FA Cup.

Their Second Division interlude didn’t last long. Things might however have been very different but for desperate luck with injuries during 1989-90. The season’s final game against promotion-chasing Leeds at Dean Court consequently became crucial for both teams, causing utter chaos as thousands of travelling fans ran riot over a sunny Bank Holiday weekend.

For all its anarchic unpleasantness that troubled fixture proved pivotal. Comparable disorder would never be seen at any British ground once Italia 90 began the gradual erosion of football’s traditionally visceral culture. Redknapp went to watch it the World Cup, but was hospitalised in Rome following a car crash; Dean Court quietly went back to sleep.

Redknapp had made his senior debut in 1965. World Cup winners Bobby Moore, Geoff Hurst and Martin Peters were members of the same team. He eventually managed four Premier League clubs, ultimately seeing Bournemouth join the same self-declared elite. No one played a more central – if inadvertent – part in football’s metamorphosis from working-class sport to global business.

The journey

Sky helpfully rescheduled the game at short notice. We therefore booked Premier Inn rooms near Bournemouth station, and – anxious lest anything else should go wrong – were driving past Wessex Way’s famous welcome sign not long after midday. Plenty of Fulham fans had already arrived. “Going to football?” enquired the man on reception.

The ground

Simon Inglis thought Dean Court “immovable, like park benches in autumn.” Its venerable Main Stand – dating from 1923 – began life as a restaurant at Wembley’s British Empire Exhibition. This unlikely structure originally featured cheerful red and white stripes along the front paddock wall, but clever 1970s reprofiling created one continuous seating tier beneath glazed roof panels.

The so-called New Stand dated from 1957. Narrow covered steps were funded by Freddie Cox’s team reaching that year’s FA Cup quarter-final, during which they beat First Division sides Wolves and Tottenham before drawing Manchester United. 29,000 fans came to see the Busby Babes; Brian Bedford put Bournemouth ahead, but two Johnny Berry goals proved enough for their famous visitors.

Two terraced ends completed this quintessential Third Division ground. That nearest Kings Park Drive had been roofed in 1936; the ironically-named Brighton Beach opposite offered basic facilities for away fans, mercilessly exposing them to Dorset’s frequent rain and fog. Bournemouth drew up ambitious plans for a new stand and sports centre here, but costs spiralled and only its gaunt steel skeleton was ever completed.

Taylor’s overreactive demands could only be addressed by completely rebuilding already adequate facilities. Plenty of space existed to do so; Bournemouth accordingly took an innovative approach that saw the pitch rotated 180 degrees, so that Thistlebarrow Road now ran behind one goal and extra circulation space was created behind three prefabricated stands. They played eight home games at Dorchester while construction work took place.

Twelve years went by before finances permitted a permanent stand on the open southern touchline. This raised capacity to its present modest level. Premier League paraphernalia apart, Dean Court’s appearance and ambience have changed little since. Everything remains quintessentially Third Division; rosy-cheeked schoolboys still chant “Boscombe, back of the net” at corners, while Dowsett’s psychodelic badge is proudly worn fifty years on.

Flesh and wine

Neither of us now had to drive until tomorrow morning. Bournemouth’s many civilised tourist attractions accordingly stood little chance against the nearest likely-looking boozer, where several hours passed happily among assorted cider drinkers, Northern expats and its acerbic Scottish landlady. We departed for the ground with their kind wishes ringing in our ears.

Down at Dean Court the King’s Plaza had opened for business. A simple tent offered free food and drink; its strict opening hours were presumably aimed at preventing rowdiness, but these well-intentioned rules actually served only to make everyone drink faster. It felt appropriate to be last out and we somehow remained upright for the few yards between here and our final turnstile.

The game

We had scarcely sat down before Antoine Semenyo loped around statuesque defenders and scored directly in front of us. It should have been 2-0 when Evanilson’s volley struck the bar; Rodrigo Muniz and Ryan Sessegnon then fluffed good chances for Fulham before visiting ‘keeper Bernd Leno pushed away a goalbound Alex Scott effort at his near post.

Fulham found another gear after the break. Alex Iwobi played particularly well and only Kepa’s excellent save kept him out. But chances had been few in this tight contest between two Europa League hopefuls; we found plenty of thinking time as our last match ticked towards ninety minutes, and put it to good use by deciding that another few pints were called for.

Teams and goals

Bournemouth: Kepa, Kerkez, Senesi (Zabarrnyi 46), Huijsen, Smith, Cook, Adams, Ouattara, Scott (Tavernier 65), Semenyo (Soler 89), Evanilson. Unused subs: Araujo, Brooks, Dennis, Hill, Jebbison, Winterburn.

Fulham: Leno, Robinson, Bassey, Andersen, Castagne, Lukic (Willian 85), Berge (Cairney 59), Iwobi, Pereira (Smith-Rowe 69), Sessegnon (Traore 57), Muniz (Jimenez 57). Unused subs: Benda, Cuenca, Reed, Tete.

Goal: Semenyo 1.

Attendance 11,195.