Fairground games and fans without trousers

Some five years ago, the Sunderland messageboard www.readytogo.net hosted a conversation about the game at Burnley in September 1978. By all accounts this was a lively occasion, which Sunderland won 2-1 despite having both full backs – Joe Bolton and Micky Henderson – dismissed before half-time. Off the pitch there was needle on the terraces, a segregation gate was forced and Sunderland fans stormed into the Burnley crowd next door where a full-scale punch up ensued. By today’s standards it was a violent affair both inside and outside the ground, but as one poster put it “As we’ve said many times before on here, bad behaviour was commonplace then. Looking back I can’t remember our behaviour being any worse than any other away game. We were by and large always pretty poorly behaved – like everyone else.”

Of interest to the visiting fans was the fact that even greater mayhem ensued at the previous match, when the Clarets had beaten Burnley in the Anglo-Scottish Cup with a goal from “the Flying Wardrobe”, Steve Kindon. “We were talking to Burnley fans in the pub before the game, and they were telling us how Celtic had wrecked the place a few days earlier”, recalls one. “Because of what happened against Celtic the searches before the match were crackers”, said another. “The police were confiscating anything you could possibly hoy.”

For those of us who grew up English and in the Seventies, the enduring image of Scottish fans in that era is forever coloured by the rampaging hordes who took over Wembley in 1977. The occasion was a 2-1 win in the annual Home International summer tournament between Scotland, England, Wales and Northern Ireland, but a solid performance by Ally McLeod’s side was overtaken by events off the park. After goals from Gordon McQueen and Kenny Dalglish decided a one-sided contest (Mick Channon’s late penalty was no more than a consolation), a large number of Scotland’s estimated 60,000 support flooded onto the pitch, destroying both crossbars and taking much of the turf and many of the stadium’s fittings home with them as souvenirs.

All the stereotypes were here – whisky-drinking, kilted, fanatical, out for a good time no matter what. To an English establishment and press obsessed with football law and order, the spectacle was unnerving and fascinating in equal measure. And the image was set in stone three months later by the game that sent Ally’s Army to the 1978 World Cup, an accomplishment that Don Revie’s England players could only dream about. Scotland needed to beat Wales in the penultimate qualifier to ensure they would go to Argentina, and Wales needed to beat Scotland to remain in contention. An already febrile tie was switched from Ninian Park, closed due to crowd trouble in the European Championship qualifier against Yugoslavia, to Anfield.

To this day Welsh and Scottish fans are split on whether Don Masson’s crucial penalty twelve minutes from time should have been awarded, with the former convinced the ball was handled by Joe Jordan rather than his marker, Dave Jones. But arguably what rankles most is that the decision to switch the match once more allowed the Scots to turn a supposedly away ground into home territory. Of the 50,000 fans in Anfield that night (a conservative estimate, given the thousands said to have got in for free), the vast, vast majority were Scots. “We got Kop tickets which was allocated to the Welsh”, recalls one Liverpool fan on www.redandwhitekop.com , “but as we walked up Walton Breck Road it was just a sea of tartan. Got to the ground and it was completely taken over by the Scottish. The only Welsh fans had been coralled into a small section of the Kop in the corner by the Kemlyn.”

The game is also remembered for the heroic amounts of alcohol consumed by the invaders. “They seemed friendly enough and one of them offered me and my mates a swig of lager”, is how one 12 year-old schoolboy recollects things. “Remember them all camping in Stanley Park, and the picture in the Echo the next night of the mountain of empty beer and whisky bottles and cans on the floor at the front of the Anny”, says another. Many describe their first sight of Tennents beer cans, featuring scantily-clad glamour models. And for some it was a chance to party: “Me arl fella and his mates from Garston used to go to Wembley every year for the home internationals to support Scotland (not a sweaty sock amongst them), and they met up with a load of lads from Glasgow. He never got home till late the next night. Me ma’s face was a picture.”

Visits by Scottish club sides to England were often equally boisterous. To this day Rangers fans commemorate their Fairs Cup visit to Wolverhampton in 1961, which local fans remember principally for a massive, hard-drinking travelling support and also for the sense of carnival created in a drab Sixties town by over 10,000 visiting Scots marching en masse to Molineux:

Now on the field below,

The boys put on a show,

The like they’ve never seen at Molineux.

And the football it was grand,

From McMillan, Scott and Brand,

When the Rangers came to

Wolverhampton town.

- Newcastle

- Leeds

By the Seventies, however, forays south by Old Firm fans tended to end less well. A Rangers visit to Elland Road in the 1968 Fairs Cup quarter-final resulted in widespread fisticuffs both inside the ground and out, while the following year’s semi-final game at St James’ Park in the same competition featured a pitch invasion and fighting sparked by Newcastle’s clinching goal (this event even made it into a Likely Lads episode, in which Terry appears in court after brawling with Scottish fans). Tommy Wright’s Goodison Park testimonial in May 1974 descended into violence when police tried to arrest a male streaker (who was English, but from the Caledonian enclave of Corby). And the few club chairmen naïve enough to arrange friendlies against the Gers were well and truly put off by near riots at Old Trafford in 1974 and Villa Park in 1976, the latter game abandoned after 53 minutes amid scenes described as “the worst football hooliganism Birmingham has ever witnessed.”

- Newcastle v Celtic, 1968 (Newcastle Chronicle)

- Newcastle v Rangers, 1969

- Villa v Rangers, 1976 (Birmingham Mail)

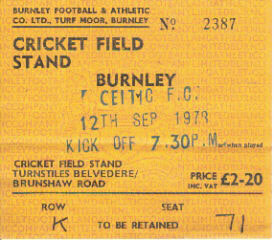

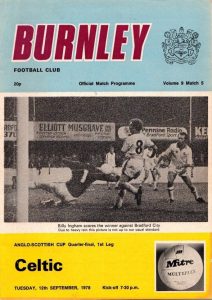

This, then, was the context for 1978 and a somewhat incongruous clash between Burnley and Celtic. The last time Celtic fans visited England in numbers had been for the 1970 European Cup semi-final with Leeds, a tie watched over two legs by 196,000 and a gala staging-post en route to their Final defeat by Feyenoord in the San Siro. The occasion now was the rather more prosaic Anglo-Scottish Cup, one of the weird tournaments that proliferated in the Seventies for no apparent reason other than to occupy second-rate teams in midweek. Started in 1975 for top-flight clubs who had not qualified for Europe, in a remarkably short time it declined – in England at least – to the point where distinctly average Second Division sides were allowed to compete. The format changed with bewildering regularity, but typically there was a knock-out phase in each country during pre-season, with group winners progressing to the “international” quarter-final stage.

The Turf Moor visited by Celtic was very different to the ground today – no, wait, actually the Bob Lord and Cricket Field Stands are exactly as they were, wooden seats and all. So (Spanish Inquisition moment) two sides were different. And actually make that one side, because the Bee Hole End (behind the goal) and the Longside (at the, er, side) were effectively a single terrace that wrapped round the corner. It was a good terrace too, more than big enough for the crowds that had watched Burnley narrowly miss a League and FA Cup double as recently as 1960. The section next to the Cricket Field was normally set aside for visiting supporters, and separated from the Burnley fans on the other side by tall iron railings. With those railings, 15,000 Celtic fans and an awful lot of alcohol, the scene is set.

What happened

Given that this was a chaotic event taking place over 40 years ago, many who were there remember the night slightly differently. But there is consensus on the following:

Celtic fans arrived in town throughout the day. Many had been drinking heavily.

When the game began they were all over the ground but mainly concentrated in the Cricket Field/Longside corner, separated from Burnley fans in the rest of the Longside by an empty area and some iron railings. These Burnley fans taunted the visitors with chants of ‘Rangers’ and ‘Argentina’. After this Celtic fans threw cans and bottles and invaded the empty piece of terracing, tearing up the six foot high railings to use as missiles.

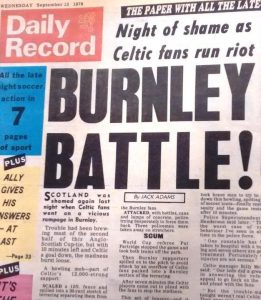

Superintendent Henderson of Lancashire Police said it was the worst hooliganism he had experienced, and that 60 people were injured including several police.

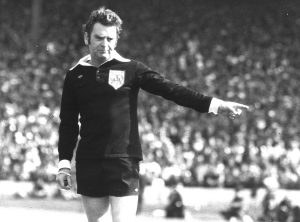

Referee Pat Partridge (a well-known character) had to withdraw the players for a time until order was restored.

Billy McNeill and the Celtic players appealed to the crowd for calm.

And once more the sexy Tennents lager cans made a vivid impression (in some cases literally) on English fans.

“Like pirates boarding a ship”

Here is a Celtic fan’s memory (via www.kerrydalestreet.co.uk )

“Celtic fans made up the majority of the 20,000 or so at Turf Moor. Hundreds of drink loaded buses left from salubrious drinking mens’ pubs throughout Scotland.

There was mayhem at service stations which involved police with dogs and wholesale looting and debauchery. From my supporters’ bus one guy was arrested and put in a van with dogs. He was released from the van by Fenian vigilantes, bloodstained and missing his trousers, but in true Celtic fashion still attended the match. While this was happening one of his mates was liberating a full tray of Penguin biscuits from the service station which he liberally distributed to all on the bus.

Little portable huts selling pints were dotted round Turf Moor. The one near us was lifted off the ground, and again liberal looting took place.

The Burnley fans then decided to chant “Argentina” at us. There was a no man’s land between both sets of fans with 6′ high iron railings on either side. A Rangers scarf was produced – cue mayhem. A sea of bottles and cans rained down on the Burnley fans. They responded with an interesting tactic. The beer cans were flattened and then skyted back at us. The casualty count was rising and eventually Celtic fans pulled down the fencing and used it as spears to throw at the police and Burnley fans, who ran onto the field.

Billy came out to appeal for calm.”

“A night I will never forget”

Burnley fans’ recollections are reproduced with thanks from www.thelongside,co.uk and the Turfites Talk site:

“Never seen anything like it before or since.”

“I worked in Accrington at the time. The landlord at our local said a van load of Celtic fans had arrived at his pub about five and they stayed till chucking out time without ever going the last 6 miles to watch the match.”

“They were there in their thousands – most of them were stupendously pissed and they were mean, aggressive and spoiling for a scrap.”

- pitch invasion…

- …the only escape

“Outside the Turf it was chaos, with no segregation between fans as the police were hopelessly outnumbered. Hundreds of Celtic fans were simply jumping over the turnstiles. There were battles everywhere – on the terraces, on the Beehole steps, outside the pie stall, behind the Longside – everywhere. The air was full of flying plastic glasses and the odd coin and real glass bottle. There was a pitch invasion which in my recollection was actually begun by the few hundred remaining Clarets in the Longside, surrounded on three sides and realising that the game was up and it was a case of the pitch offering the only escape route. The Jocks followed, having broken down the fencing that theoretically should have separated the two sets of fans on the Longside. There was then a massive running battle on the pitch, and it was getting very nasty indeed.”

“Going for a slash was quite an ordeal. They were skimming empty whisky bottles along the back wall as soon as you popped your head out. It was like one of those fairground games.”

“My abiding memory is that the Longside was taken- they broke through the fencing and used the debris as missiles. There must have been 5,000 more than the official figure suggests inside the Turf that night, all of whom were Celtic, as the police gave up and just let them jump the turnstiles. Sheer weight of numbers told, literally – I reckon the crush is why the fence gave way and it’s a miracle there weren’t any deaths. Once the fence came down the Clarets had nowhere to go but onto the pitch.”

“I was in the relative safety of the Cricket Field stand at the time. However I remember Celtic fans destroying the fence between the fans and using pieces of it as spears. The cops with their dogs and horses had no chance. You should have seen Burnley town centre the day after the game. I do recall a group of Burnley fans remaining in the Longside – not many though, and they must have been scared to death.”

“Like all Clarets who witnessed the trouble it is a night I will never forget. We were in the Cricket Field stand adjacent to the away fans. Initially, they concentrated on the Burnley fans next to them in the Longside, heaving whatever they could over the dividing fence. They then ripped up the fence and hurled the metal javelins at our fans. Later in the match they started to climb into our stand, some with blood soaked bandaged heads, looking for all the world like pirates boarding a ship.”

“The Longside had a fence to separate the fans in those days and after throwing hundreds of empties over it they then proceed to break the fencing up. They threw concrete and fence posts at the Burnley fans. I saw a man close behind me get struck with a lump of concrete and fall to the floor with blood gushing from his head.”

“Neither police nor the club had a clue how to handle it. The game continued as hundreds of Burnley fans tried to escape the area. The game was suspended eventually to allow them to escape and watch the game from elsewhere in the ground.”

“It was a miracle nobody was killed or severely injured.”

“I was scared to death. Absolutely the worst night of violence I have ever experienced. Bottles, steel railings, bricks and any other detritus the Celtic fans could find were coming our way.”

“I was with my sister and I honestly thought we were goners.”

“I was at the midpoint of the home end of The Longside – halfway along, halfway down. It was horrible. It wasn’t just the debris coming at us from the right, they’d found their way across at the back of the Longside, where the steps led down to the “toilets”, and so we got rushed from the right and from behind.”

“Was shepherded off and out of the ground by police horses, and not let back in.”

“I didn’t bother going up to Glasgow for the return leg.”