The club

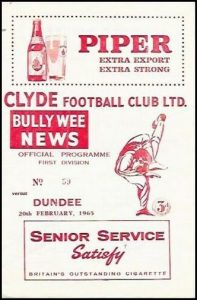

Clyde have always been known as the Bully Wee. It’s one of those football nicknames whose forgotten origins haven’t stopped an industry developing around trying to explain them. The most obvious seems to be a combination of “excellent” – in Victorian parlance, “bully” – and “small”. Both apply equally well to a club formed by gentlemen rowers whose principal hobby was messing about in boats.

Clyde are often thought of as a Glasgow team but actually come from Rutherglen in Lanarkshire, just south of the city boundary. Different rules imposed by the respective councils during World War II led controversially to their Shawfield ground being allowed to host larger crowds than Ibrox and Parkhead. Geographical confusion caused more lasting resentment in 1967, when a third placed finish behind Celtic and Rangers would have meant qualification for the Fairs Cup but for a rule that only one club per city could compete. When Clyde denied being from Glasgow UEFA smugly pointed out their participation in the Glasgow Cup and membership of the Glasgow FA. The Bully Wee never came close to European football again.

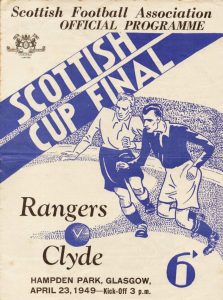

- 1949

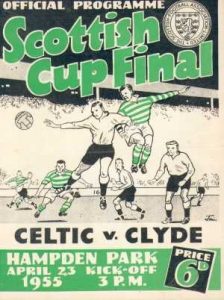

- 1955

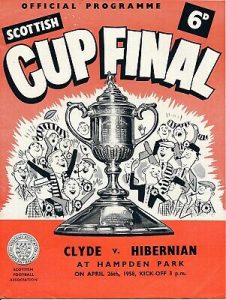

- 1958

This was an era when Clyde – as so often – punched consistently above their weight. The team were more or less permanent fixtures in the top division and this would remain the case for some time longer. Shawfield’s proximity to the Old Firm through long years of struggle and often penury was at once a challenge and an opportunity, a trade-off between competition for support and the benefits of co-existing in a working-class corner of a football-mad city. The Fifties – once the disappointment of a 4-1 defeat to Rangers in the 1949 Scottish Cup final had faded – were particularly successful. The team enjoyed Cup wins in 1955 and 1958 and last-four appearances in 1956 and 1960, and reached the League Cup semi-finals in 1957 and 1958.

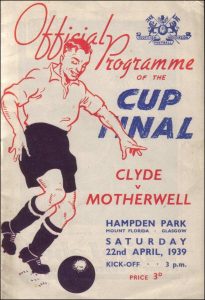

- at last

The Cup became a Holy Grail for Clyde in the years before World War 2. They were beaten finalists in 1910 and 1912 and lost in the semis of 1909, 1913, 1936 and 1937. Their fans can’t, then, have been optimistic travelling the short distance to Ibrox for the 1938-39 Third Round, but a 4-1 triumph against a stellar Rangers side – in which hotshot Willie Martin bagged all four Clyde goals – paved the way for cagey wins over Third Lanark and Hibs that propelled the Bully Wee into a third Final. Motherwell were favourites to win but Clyde weathered early pressure, took a stranglehold on the game with goals from Wallace and Martin and nailed it with another couple in the dying minutes. At last the Cup was theirs.

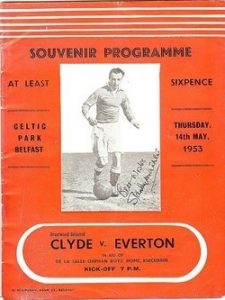

Doyen of the Bully Wee in the pre-War era was Matthew “Mattha” Gemmell, who went to Shawfield as groundsman in 1898 and eventually spent 30-odd years as trainer. He owed this promotion in no small measure to predecessor Bill Struth. A friendship developed between the two that continued after Struth left Shawfield in 1914 to move to Rangers. While Struth became Ibrox’s greatest and longest-serving manager, Gemmell – born at nearby Bridgeton – was happy to stay at Shawfield. He was by all accounts a gentle, humane man with a fine sense of humour that “Solly” immortalised in a hard to obtain wartime biography, Mattha Gemmell o’Clyde. Over 30,000 packed the ground to see Gemmell’s 1945 testimonial between Everton and an all-star Glasgow select.

Equal friendship grew between Clyde and Everton. The two played each other again in a 1953 benefit at Belfast Celtic’s ground in aid of the De La Salle Orphan Boys Home, a game in which Stanley Matthews guested for Clyde. Prolific scorer Tommy Ring moved to Merseyside from the Bully Wee in 1960. He was a star of the brilliant 1950s team which is generally regarded as the finest in Clyde’s history. As one forum contributor to glasgowguide.co.uk puts it:

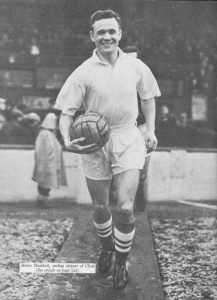

“Oh, the memories! McCulloch, Murphy & Haddock…Walters, Findlay and Clinton…Herd, Currie, Coyle, Robertson and Ring – what a team that was. I saw them play away back in the good old days. Four of this team played for Scotland…Harry Haddock, left back – the most genuine, ‘cleanest’ left back you ever saw. George Herd – a fine dribbler, and an artist on the ball. Archie Robertson – poker-backed general of the forward line, and a great penalty-taker. Tommy Ring, outside left – bamboozler of right backs!”

Shawfield

Clyde’s first ground, Barrowfield Park, stood directly opposite Shawfield on land flanked by Colvend Street and Carstairs Street. The river is narrow here and a modern footbridge connects the two sites. This walk would have taken rather longer in 1898, when – eight years into their Scottish League history – the club decamped across the water to a more promising location in the shadow of Whites’ chemical works. This was Shawfield, an oval trotting track with space for a pitch at its centre.

J & J Whites’ enormous plant filled the area between Glasgow Road and the train sheds at Polmadie. It was notorious for low wages, dangerous working conditions and the horrific medical side-effects suffered by employees. In 1899 Keir Hardie himself took up the cause of “White’s Dead Men”, so-called because of a ghost-like pallor caused by the chromium dust they handled. There was a small shipyard, Seaths, next to the Dalmarnock railway bridge. And to the north of the new ground was Richmond Park, also freshly built and facing the sprawling residential district of Oatlands and its streets of four-storey sandstone tenements.

Two more clubs took up residence nearby in due course – Rutherglen Glencairn at Southcroft Park in 1897, and Shawfield FC at Rosebery Park two decades later. Both became successful junior teams and a 1939 cup final between them at Celtic Park drew a crowd of 22,000. (A third junior club, Pollok, groundshared with Shawfield during the 1920s.) Rosebery Park staged football until the 1990s and Southcroft Park survived until 2007. The former stood at the centre of a network of streets opposite the park, while the latter was next to the Glencairn Social Club and near the Glens’ present ground.. A surviving stretch of perimeter wall is painted with a mural commemorating their history.

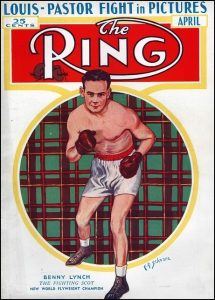

A basic stand was hurriedly built for Shawfield’s opening game. This burned down in 1917 to be replaced by a more substantial structure holding 1000 spectators. The ground later acquired covered terracing along the far touchline and behind the park end goal. Athletics took place there prior to 1932, and then greyhound racing and boxing. Its finest moment as a fight venue arrived in 1937 when 38,000 turned up to see world flyweight champion Benny Lynch defeat Liverpool teenager Peter Kane. Gorbals-born Lynch was the ultimate local boy made good. He graduated from a boxing booth on Glasgow Green to the global stage, but this proved one of his last fights before a tragic lapse into overeating, alcoholism and vagrancy.

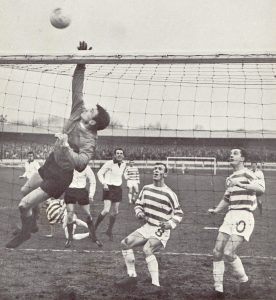

By 1957 Shawfield’s capacity was some way short of the 50,000 that squeezed in for games against Celtic and Rangers before World War One. But visits by the Old Firm continued to be gala occasions, not least because supporters of both claimed Clyde as a “second” team. So the ground was packed on a foggy December day for a game against Celtic, and this resulted in a terrible accident. When McPhail scored for Celtic early on a crowd surge collapsed a long section of perimeter wall, which toppled onto schoolboys sitting on the perimeter track. Spectators, police and players had to carry the injured boys to safety. Twelve were admitted to hospital and a 9 year-old from Bridgeton died.

The biggest crowd in modern times, meanwhile, attended a David Cassidy concert in 1974. Like most public outings by the Partridge Family star this proved notable for teenage fainting, screaming and general hysteria. The compere was eccentric Radio Clyde presenter and erstwhile Parkhead tannoy man “Tiger” Tim Stevens – dressed in a tiger suit for the occasion – and, just in case anyone thought Stevens wasn’t flamboyant enough, Showaddywaddy were the supporting act. In the event Cassidy only played two more concerts. His next show, at London’s White City, was marred by the death of a 14 year-old girl in a crush and, shocked, he made his last ever touring appearance at Maine Road four days later.

At its peak this ground was the centre of a busy community. As Danny Gill wrote in his Glasgow memoir Emah Roo, “Shawfield Stadium was famous for holding greyhound racing on Tuesday and Friday nights and there was always a good crowd that turned up. There were more winners than losers I’m afraid to say with the punters, although lots of people on the sou’ side would put on a bet with the street bookie. It also had a lounge bar and you could have a dance there too at the weekend, just ordinary everyday things we all done in the Gorbals and Oatlands. Then later there was motor bike speedway racing so Shawfield Stadium has always been a busy wee place.”

Landlord and tenant

Dog racing boomed in the late 1920s and Clyde – ambitious lessees of an oval stadium – wanted to cash in. But the League took a dim view of greyhounds and made the club refuse a 1928 offer from the Belle Vue company of Manchester to bring them to Shawfield. Nothing daunted, wily Bully Wee chairman John McMahon arranged for the board of directors to set up their own racing company. So successful was their strategy that the greyhound business proved more viable than the football operation and in 1935 was sufficiently profitable to buy the freehold of Shawfield, something the football club had been attempting for years. It would prove a shortsighted decision with far-reaching consequences.

One very visible product of the greyhound track was the appearance of a handsome totaliser board, or “Tote”, at the open end of the ground. The Tote was a Government attempt to regulate betting at race and dog tracks and to clamp down on unlicensed bookmaking. Its principle was that a percentage of profits from betting should be ploughed back into sport. On a race day the Tote also served the very practical purpose of letting punters know how much they would win. Despite the popularity of unofficial street bookies, Shawfield’s Tote turned over nearly a million pounds a year during the 1950s. As repurposed the ground also featured track lighting, betting booths, social clubs and restaurants.

- all pics: Bob Lilliman

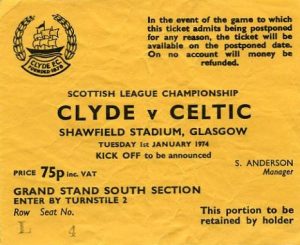

The beginning of the end for football at Shawfield came in September 1975, when the main stand was yet again engulfed by fire – this time the blaze seriously damaged the ground’s electrics as well as the boardroom and manager’s office (whose incumbent at that time was former Rangers reserve-team coach Stan Anderson). Greyhound racing had been in decline since off-course betting was legalised in 1963, meaning little money was available for refurbishment. Soon afterwards Shawfield’s ownership came into the hands of the Greyhound Racing Authority. This was by now essentially a property redevelopment company and in 1983 the ground was put on the market with Clyde given notice to quit.

The last match took place in April 1986. It ushered in a homeless spell during which the team played at Partick for five seasons and Hamilton for a further two and a half. Neither arrangement was popular with the fans (cohabiting with their deady rivals at Firhill proved particularly uncomfortable). Clyde then uprooted to the unlikely surroundings of Cumbernauld and entered into partnership with the local development corporation, who saw the procurement of a football team as the biggest opportunity to put the town on the map since Gregory’s Girl was filmed there in 1981. The club remain based at the new town’s Broadfield Stadium to this day.

Broadfield is tidy, brutalist and vaguely imposing. It has three stands with far too many seats for the five hundred or so who turn up for matches. The club threaten periodically to leave, most notably in 2004 when the ground’s lack of a fourth side looked set to derail an unlikely tilt at promotion to the Premier League. Alternative proposals have included – tantalisingly – a return home to share with Rutherglen. But for now the Bully Wee remain in exile.

Shawfield today

The ground stands next to an elevated section of the M74 and is therefore one of Glasgow’s better-known landmarks. A 2011 extension to the existing motorway isolated an already much denuded area, as well as obliterating both Southfield Park – which had the misfortune to be directly in its path – and the remains of Rosebery. Recession and clearance have ripped the heart from surrounding districts. There’s an uninterrupted view of Parkhead across a square mile which until quite recently was a busy vista of factories, tenements and tower blocks.

It’s no coincidence that Clyde’s decline in fortunes from the early Seventies mirrored an industrial level of depopulation in areas from which the club traditionally drew support. Huge swathes of Bridgeton, Dalmarnock, Oatlands and Gorbals were razed to the ground and generations of fans relocated to projects and new towns on the city’s fringes, from where they showed little inclination to return on a match day. Viewed in this context the switch to Cumbernauld – from the 1950s onwards a popular destination for resettled inhabitants of Clydeside – has a certain logic. If the fans wouldn’t come to Clyde then it was eminently sensible for Clyde to go to them.

Against all odds Shawfield remained a community hub following Clyde’s departure. First an action group rallied by ex-bookie, reporter and stadium manager Billy McAllister staved off the GRA’s application for residential planning permission, then a business consortium re-opened the ground for greyhound racing. For the last 20 years this has been Scotland’s only licensed dog track and the sole survivor of a proud tradition. Spectator facilities are maintained up to a point but with such a large, sprawling site it’s a challenge to keep up appearances. The football pitch had its corners unceremoniously sliced off in 1988 when the Glasgow Tigers speedway team became the stadium’s new tenants. The famous Tote was demolished in 2004.

- bricks

- bold

- blocked

- broad

- long

- litter

- landscaping

- lighting

- hoarding

- hound

- high

- Deco

- driving

- dreaming

I took these pictures on a gritty October day. I’d been visiting another of Glasgow’s great working-class palaces, the Barrowland ballroom. The south side is windswept after Gallowgate. Dinky newbuilds have replaced the tenements around Richmond Park, but the stadium is surrounded by undeveloped land still toxic – as was the condemned shell of Rosebery Park in its later days – a half-century after the closure of Whites’. For all its faded art-deco charm Shawfield is a busy wee place no longer.