Coventry City 2 Rochdale 1

League 1

Saturday 16 November 2019

The context

Another home ground for Coventry. The circumstances of the Sky Blues’ present nomadic existence are complicated – but suffice to say the fans are being royally shafted, and a proud part of their city’s heritage systematically destroyed, in yet one more example of a football club falling into dubious hands. It’s a disgrace that these things are allowed to happen.

When Kieran and I fell in with a pub full of City supporters ahead of the 2018 play off final a very good time was had by all. They don’t deserve this nonsense. So rather than talk about their club’s unique history while visiting a ground twenty miles away, I’ll write about Coventry when I next go to a game in Coventry. That day really can’t come quickly enough.

The history

There’s something about a football stadium on a hill. Celtic fans call Ibrox ‘Castle Greyskull’, and St Andrew’s has the same brooding presence. It glowers down on the city centre and seems to be reminding visitors just how long their walk will be. In the 1980s this was a hostile place described by one policeman as “the most desolate, scruffy, windy ground I ever visited.” Much of the surrounding area had been reduced to rubble-strewn wasteland, and a crucifix dangled bizarrely from each floodlight pylon as part of an initiative by the ever-rational Ron Saunders to exorcise a gipsy curse he thought was affecting Blues’ form.

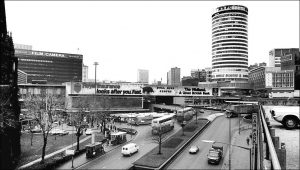

It’s hard to convey just how tricky that walk could be to people who never saw the Zulus performing Saturday circuits around New Street and the Bull Ring, mobbing up in the Bar St Martin and snapping at the heels of a nervous away support and their jittery escort along Digbeth and High Street Deritend. Entering the darkness of the bridge under Bordesley station always felt like the point of no return on a grey, gritty winter Saturday. When I recall coming here in those days it’s of menacing railway arches and side streets, unexpected alleys and dead ends to trap those foolish or panicked enough to stray from the path.

I don’t think many matchgoing fans were too surprised when St Andrew’s was the setting – on 11 May 1985 – for the era’s biggest and bloodiest showdown. This pitched a nihilistic Leeds support against just about every lunatic in South Birmingham. The final whistle was an ignition point at which the flames of a simmering day were fanned by overcrowding, disorganised policing and sheer, brutal malice into violence that left one dead and five hundred injured. Although we didn’t know so at the time this proved – mercifully – the high-water mark of a nasty, insidious, creeping one-upmanship that had been building over the previous two decades. For those of us who went to watch and not to fight it was a turning-point.

But there are two sides to every story. Although football ground chronicler (and Villa fan) Simon Inglis once referred to St Andrew’s as “grim and proletarian”, there was a touch of envy in his grammar-school aversion to a world he could never understand. In its heyday this was a peoples’ palace like all the real old working-class grounds. The underdog efforts of City’s players represented escape for people who often didn’t have much else going for them, while Blues’ crowd reciprocated with passion and loyalty underwritten by (however territorial) a sense of community. And so what if this parochialism had consequences outsiders might not necessarily like? No-one forced them to come.

The essence of Birmingham City was perfectly illustrated on 27 December 1982. This was the day an epically struggling home side gave their glamorous neighbours a spanking they have never forgotten. Villa arrived in B9 as darlings of the media, fancy Dans fresh from a League title and European Cup win. Blues meanwhile were a cynical rag-tag of free signings, youth products and journeymen assembled by Saunders in diabolical revenge on the world following his sod-you exit from Villa Park earlier in the year. But that cold, damp afternoon 43,000 fans crammed into the crumbling old ground and saw these unlikely heroes win 3-0 in a simmering, volatile atmosphere none of them have ever forgotten.

The journey

John used to drive a delivery van in Birmingham so we piled into his car and left him to navigate. He paid us back by planning a route incorporating two of his favourite places, Villa Park and the Eagle & Tun. At least (unlike most people round here) he doesn’t claim to have been in the latter when UB40 rocked up to film the video for Red Red Wine. We also took a diversion down Witton Street to see if the Garrison had re-opened. It hadn’t.

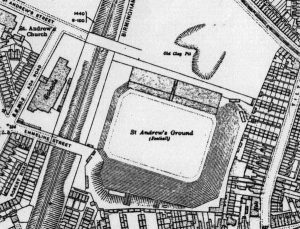

Coventry aren’t pulling big crowds so we were able to park right outside the Railway Stand gates. This used to be a nasty corner at one end of Ada Road – now a stopped-up stub – which ran past St Andrew’s School to the old turnstiles on Emmeline Street. The Railway End was the focus of the Leeds riot, and after the game most of the equipment and indeed the fabric of the school playground was demolished and thrown at the police. Today however there was a relaxed family atmosphere in the Main Stand forecourt as players arrived in cars and early arrivals chased autographs.

The ground

Most of St Andrew’s was redeveloped following the Taylor Report but the ground still occupies much the same footprint as when it opened in 1906. At that time Bordesley was far less built-up than now, and the site contrasted pleasantly with the club’s first and somewhat cramped home at Muntz Street. The construction work wasn’t without complications, not least a spectacular falling-out with some gipsy workmen over a dead horse which ended up in the Tilton End foundations and led to the famous curse. (When we tried to sit in the Tilton today the stewards shooed us off and said it was “a no go area”. Maybe there’s something in the legend after all.)

The present-day Kop and Tilton stands are actually one stand, a single uninterrupted L-shape that wraps around the Tilton Street corner. They follow the line of a former terrace which dated from the ground’s early days. St Andrew’s was unique (and rather confusing) in that its Kop was a side and not an end. This hugest of terraces had been built, as was the custom, into the side of a spoil heap created when the pitch was excavated. The steepness of Coventry Road meant that you entered the Kop via staircases at the Railway End but at street level where it joined the Tilton. The modern concourses are arranged in much the same way.

The old Kop was a fearsome beast. “You couldn’t hear the Villa fans singing. You could see their arms move and point but the noise in the Spion just drowned it out,” was how one fan recalled that 1982 game. Visiting supporters, meanwhile, were accommodated in the Tilton corner next to the Main Stand. This was a wedge-shaped enclosure, vigorously fenced and separated from the unfriendly Blues element next door by a huge net and a sizeable chunk of no-man’s-land. It had an afterthought of a cover built straight onto the back of the terrace. This was equally capable of being climbed by errant youths and causing head injuries when the away side scored, neither of them unusual occurrences at St Andrew’s back in the day.

The topmost corner of the away end had been extended and heightened in the 1960s. Narrow steps descended from the open area behind it to a yard beside the Main Stand, where there were toilets and an exit gate – the first flight was at right angles to the terrace, with the boundary wall at its foot. This cramped pinch-point contributed to the defining tragedy of the Leeds game. As the ground finally started to clear a packed press of Leeds fans became squeezed between the 12-foot high wall and police batoning them down the stairs from the top. The resulting pressure caused the brickwork to collapse outwards like a house of cards, and fall onto people underneath who had chosen that very place to shelter from the violence.

The end few rows of the modern Tilton now cover this spot, while the Main Stand – a simple 1950s construction very like West Brom’s erstwhile Rainbow – is in exactly the same place and not much changed. Its near-identical counterpart behind the Railway End, the City Stand, has been superseded by a modern version that somehow seems much taller than it needs to be. This stand and the new Kop have encroached so far onto Emmeline Street that there’s no longer any room for a turnstile block. An area that was once a hive of (not always respectable) activity is cut off from the rest of the ground. The old bridge over the railway is eerily deserted.

Flesh and wine

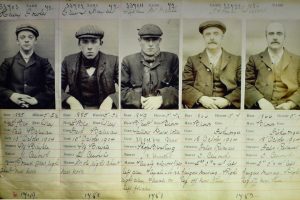

History books tell us that hooligans known colloquially as Peaky Blinders caused trouble around Birmingham from Victorian times. The city wasn’t unique in this respect – most had violent delinquents such as London’s Hooligans, the Scuttlers of Manchester, the Liverpool Corner Boys and the Billy Boys in Glasgow. But through the medium of television (mixed with a fair amount of invention and factual manipulation) the Peakys have become a national cause celebre and an iconic image for Birmingham itself.

The TV series was inspired not by the original Peakys, who were basically street roughs and petty criminals, but by racecourse turf wars of the 1920s and specifically the Kimber gang. Billy Kimber was from Summer Lane in Newtown. Eventually his influence spread as far as London – this brought him into conflict with Jewish interests led by Edward Emmanuel, and also with the notorious Sabini mob. Characters based on Emmanuel and Sabini appear in early episodes of the programme. Kimber was badly beaten up and shot in early 1921, and then saw most of his henchmen put away after they brutally attacked a coachload of Leeds bookies at Epsom believing them to be the Italians. The police tracked down the Brummie gang quite easily. They just looked in the nearest pub.

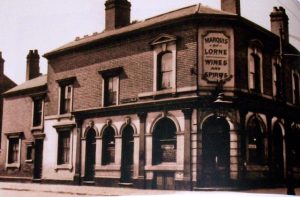

The morphing of these two legends has had some interesting consequences, not least the spectacle of Aston Villa’s star player sporting a daft haircut made famous by a fictional take on Depression-era fans of his club’s deadliest rivals. Another is Peaky-themed establishments popping up all over the place. There are some particularly shocking examples in the vicinity of St Andrew’s, but you don’t need to look far to find a couple that have genuine history. The aforementioned Garrison was portrayed as the Shelby family’s headquarters and used to be a haunt of the original street gang, while the Marquis of Lorne, another Peaky pub, was shown being destroyed by an arson attack in the second series after Arthur Shelby was involved in a fight there.

The Marquis is still very much in business although nowadays called the Roost. This well-known Blues boozer is your classic Tardis. The quest for more drinking space has seen it expand into a rear yard that since our last visit had gained not only a roof but also a snack bar disguised as a garden shed. The pub has been adopted by the livelier element among Coventry’s diasporic fans and today it was literally rocking. A mobile disco filled one corner of the Victorian tap room, and the whole clientele was bouncing to a mix of rude boy sounds and insulting Wasps, Sisu, Coventry City Council and Aston Villa to the tune of Tom Hark.

Food-wise, what to choose? There were burgers available in the beer garden and, as ever at St Andrew’s, the opportunity further down the road to be served a bad hot-dog with greasy onions out of a food van by a grumpy yet golden-hearted Brummie sourpuss. But in the event we spent so long drinking that we had to settle for pies on the concourse. We could have done a lot worse.

The game

This pitched third-placed Coventry against a Rochdale side in lower mid-table. I still find it difficult to compute Dale without Keith Hill in charge, and even harder to accept that they’re managed by someone called Brian Barry-Murphy. But the hyphenated one set his side up well and they were deservedly ahead when skipper Ian Henderson stroked an excellent cross from Callum Camps past Marko Marosi.

On an afternoon of feinting and parrying it was no surprise that Jordan Shipley equalised just before the break. Zain Westbrooke played him in with a ball over the top, and although Robert Sanchez got in the way of the first effort he couldn’t legislate for his defenders running about like headless chickens and giving Shipley a second chance which he gratefully converted. This set City up nicely for a dominant second half and the points were finally secured by a Liam Walsh wondergoal, a masterpiece of mazy running and defender-beating that culminated in a left-footed rocket into the roof of the Tilton End net.

- closed

- deserted

- home

- away

- shop

- Kop

- no-go

- remembered

Teams and goals

Coventry: Marosi, Rose, Hyam, Drysdale, Dabo, Eccles (O’Hare 88), Walsh, Mason, Westbrooke, Bakayoko, Shipley. Unused subs: Watson, Allen, Wilson, Kastaneer, Bapaga, Burrows.

Rochdale: Sanchez, Keohane, O’Connell, Williams, Done, Camps, Ryan (Tavares 78), Morley, Wilbraham (Andrew 81), Hendereson, Pyke. Unused subs: McShane, Baah, Gillam, Hopper.

Goals: Coventry: Shipley 42, Walsh 72. Rochdale: Henderson 28.

Attendance: 5433.